Psychologists and educators must be more aware of their sexist biases when working with female patients and students who have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as symptoms present different in girls and women.

Gendered socialization, or the way boys and girls are raised differently based on their sex, often causes ADHD symptoms to differ between boys and girls.

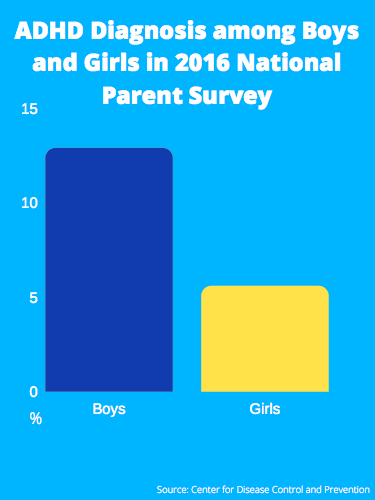

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, boys are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with ADHD compared to girls. Many assume this means that boys are just more susceptible to having it, but the number of individuals diagnosed is not equivalent to the actual number of people with it.

Symptoms present differently in men and women because of the types of issues they are prone to in the first place. According to CHADD, an organization for children and adults with ADHD, women with ADHD often also have higher rates of eating disorders, alcohol addiction and low self-esteem compared to men with ADHD. They are also diagnosed at an older age, a problem that is rooted in sexism and amplified by a misunderstanding of common ADHD symptoms.

Society teaches girls to be quiet and accommodating, which can lead to a few different outcomes for girls with ADHD. ADHD is split into three types — primarily hyperactive, primarily inattentive and a combined type, according to ADDitude, a website about issues relating to ADHD.

Hyperactive girls may be punished in school for being too talkative and impulsive. Because society considers many hyperactive traits “masculine,” teachers may be less forgiving of these behaviors in female students. The saying that “boys will be boys” is exemplary of how society assumes boys are more reckless and active than girls.

Girls that struggle with inattentive ADHD are labeled as spacey, forgetful, lazy and major procrastinators. According to ADDitute, inattentive ADHD is both the most misunderstood type of ADHD as well as the most common type for women to have. Additionally, only 20-25% of people with ADHD have the hyperactive dominant type, meaning the most common type is also the least studied.

The underdiagnosis of girls with ADHD puts them at a huge disadvantage in school. Without a proper diagnosis, girls with ADHD cannot get proper help. This can cause them to miss assignments, have trouble concentrating in class or cause disputes with other students. Teachers, unaware of an underlying issue, will often punish undiagnosed students rather than get them necessary help.

In my own experience as a child, if I forgot to do an assignment or forgot to bring a workbook home with me, recess or other fun activities were taken away from me. I was either scolded or offered extra help in the subject I forgot to complete, which was well-intentioned but not the help I needed.

I had no problem with the actual material, but instead I had trouble with time management and organizational skills. Educators tend to equate students’ intelligence with how well they fit into the structure of school.

As I got into high school, these problems persisted. During a parent-teacher conference, one of my teachers stated, “She acts like the boys in class. She does just enough to get by.”

I never wanted to merely “get by” in school. However, as I grew up I developed strategies to get good grades with a minimal amount of effort, not because I hated learning, but because it was the best I could do with the issues I had.

The individualist structure of school and society caused me to believe my struggles were personal faults rather than neurodivergence, which is a term used to describe those with mental or cognitive disorders. Furthermore, because I’m female, I internalized my problems because I didn’t want to be a burden to my family or teachers.

ADHD is manageable with medication, therapy and compassion from others. However, those with it cannot begin to manage it if they are unaware that they have it.

Students, especially female students, with ADHD should not have to go undiagnosed as we adapt to a system that puts us at a disadvantage. Educators, psychologists and everyone in general must reframe the way ADHD is recognized in children and create diagnoses that are inclusive of both genders as well as variants within the condition.

This story was written by Jenna Koch. She can be reached at jenna.koch@marquette.edu.