Even as the curve begins to flatten in some areas of the country, the coronavirus continues to devastate America’s correctional system.

This, however, is no coincidence. Prior to the pandemic, prisons already were operating under suboptimal conditions. Correctional facilities were largely overcrowded and lacked adequate health care staff, leaving inmates and surrounding communities and at extreme risk to COVID-19.

As of April 28, the New York Times identified nearly 200 hot spots for COVID-19 cases in the United States, many of which were among jails and prisons.

The worst hit of these locations is Marion Correctional Institution in Marion, Ohio which, according to the New York Times, currently has the country’s single largest outbreak with 2,197 confirmed cases. The prison reported March 29 that a staff member had contracted the first case. Less than a week later, the first inmate to have COVID-19 was reported, and within the following 16 days, the prison had accumulated over 1,800 confirmed cases. Marion Correctional, however, is only a fraction of a much larger issue.

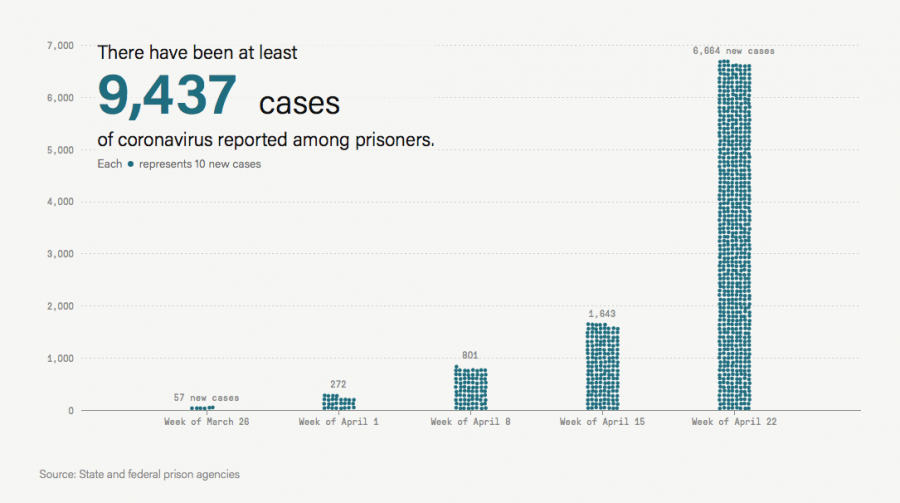

Since mid-March, The Marshall Project, a nonprofit organization of journalists, has been tracking the pandemic within U.S. prisons — the findings have been frightening.

Each week, the number of new COVID-19 cases within the incarcerated population has more than doubled. The Marshall Project reported 57 new cases during the week of March 26, when data was initially collected. In the last week, the organization reported 6,664. The total number of cases among inmates now stands at 9,437 with an additional 3,950 cases among prison staff.

The trend has sent prison management, the Department of Corrections and state and federal governments scrambling to find a solution. The Federal Bureau of Prisons has allowed shortened sentences and alternative home confinement for eligible inmates to reduce the prison population in the effort to stem the spread of COVID-19.

In context, however, the state of the U.S. correctional system today seems almost prophetic.

In an NBC interview, Dr. Homer Venters, the former chief medical officer of New York City’s correctional health services, said, “We’re in a very perilous stage right now. … It’s just a matter of time before we see cases inside jails and prisons.”

Just a few months earlier, China was in a similar position to the one the U.S. appears to be experiencing now. According to Beijing’s National Health Commission, there were an estimated 76,000 cases of coronavirus in the country around February 21. More than half of which originated within prisons in the Hubei province Justice Ministry official He Ping told Business Insider in mid-February.

Even with the establishment of social distancing guidelines, U.S. prisons are especially hazardous. Whereas those outside prison walls can consciously avoid their peers, individuals on the inside do not have that choice.

According to a Department of Justice report released earlier this year, the population within federal prisons surpasses their recommended capacity by as much as 19%, which not only makes social distancing difficult but impossible to implement in the correctional facilities’ already compact environment.

What’s worse is that health care personnel in prisons is severely lacking. In 2013, there were as many as 116,000 unfilled nursing positions among federal prisons, according to a Journal of Correctional Healthcare study.

Like so many other issues surrounding medicine, race and socioeconomic status, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the flaws within the U.S. correctional system. American prisons were already unfit to operate under normal circumstances, let alone during a national crisis.

After the virus subsides in the U.S., state and federal policymakers must acknowledge and address the poor condition of prisons in the country. The wellbeing of our correctional system is not only critical to the inmate population but those who work within prisons and the communities that surround them.

According to the Marshall Project, 141 inmates and 13 staff members have died due to COVID-19 — in no small part due to America’s neglect of its correctional system.

Sentences have become death sentences and punishments, cruel and unusual. It’s time for immediate and radical intervention.

This story was written by Nicole Laudolff. She can be reached at nicole.laudolff@marquette.edu.