Students, higher education professionals and community members gathered at Alverno College for a summit to discuss underrepresentation on college campuses Feb. 21. The summit, Advancing Equity in Our Colleges and Universities, was hosted by the Wisconsin Center for the Advancement of Postsecondary Education and the Hispanic-Serving Institution Network of Wisconsin.

Given the rapid growth of the Hispanic community in Milwaukee, six institutions — Marquette University, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Mount Mary University, Milwaukee Area Technical College, Alverno College and University of Wisconsin-Parkside — have committed to attract, support, retain and graduate increasingly diverse students from traditionally marginalized backgrounds.

Alverno College met the enrollment criteria to become a designated HSI in 2017, meaning its student population is now at least 25% Hispanic. It is the first — and only — HSI in Wisconsin.

The other five schools have yet to achieve HSI status because they have fallen short of criteria laid out in Title V of the Higher Education Act.

Yet, at this summit, there is collaboration.

There is hope.

—————————————

The Advancing Equity summit aims to support the broad educational aspirations of the Latinx community. For one community within the Latinx population, however, the path to higher education is fraught with uncertainty. In addition to working towards HSI status, figures in both the Marquette and UWM communities have devoted themselves to supporting undocumented Latinx students.

“Faculty of color serve as…mentors and advisers for underrepresented students,” Jacqueline Black, associate director of Hispanic initiatives at Marquette and co-host of the summit, says.

There are 2,383 students of color and 193 full and part-time faculty of color at Marquette, as of Fall 2019. People of color make up 28% of the student body and 14.9% of current faculty. What is most important, Black says, is putting a face and a name to the statistics.

“Our students are more than just data points,” she says.

One student, one professor, one mental health counselor and one cultural center director opened up about their successes and struggles in higher education.

This is what mentorship means to them.

—————————————

It’s an unassuming accessory, adorned with colorful plastic beads — royal purple, matte black, gold and lime green. The string is thin, looped in delicate and snug bows. It offers a reminder of her unique position.

Nancy Suarez Jiménez, a sophomore in the College of Arts and Sciences, is a resident assistant. Part of her job, she says, is engaging in personal reflection. The bracelet-making activity was one such instance. It was part craft, part introspection — an activity held at a staff meeting for other RAs. She was asked to reflect upon her identity in the form of jewelry making; each bead was to represent a personal privilege.

Whereas other RAs had fully adorned jewelry by the end of the exercise, Jiménez had only claimed a few beads. She says she teased her friend about it.

“I was like, ‘Look, it’s like we’re fishing! Your worm is bigger than my worm, (so) you’ll catch fish,” Jiménez says.

Some undocumented youths who entered the country as children were protected from deportation under an administrative program from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in 2012. This protection was called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

800,000 individuals are protected under DACA, with Jiménez and her older sister being two of them. She says she remembers the exact day the executive order was announced, seeing her mom and her sister burst into excited laughter and tears.

“My sister goes, ‘Nancy, we can work! We can drive!’ And I’m like, ‘We couldn’t do that before?’” Jiménez says.

The program helped Jiménez go to college — DACA allows its recipients a worker’s permit, a license and a temporary Social Security number. Otherwise, she says her path would have been unclear.

DACA students are not eligible for federal financial aid, according to the Federal Student Aid Office. Jiménez says Marquette helped her receive scholarships to cover the entire cost of tuition.

In 2017, DACA came under siege. President Donald Trump cited the lost job opportunities for natural-born citizens as part of his reason for ending DACA.

Jiménez says when she went to the Career Services Center and asked what she could do after graduation, she received heartbreaking news. She says the adviser told her she might have to change her major to something like business — something that would not require a PhD.

Jiménez wants to become a psychologist so she can help other undocumented students or children with trauma. She’s already doing that work at Marquette.

As a leader of the Dreamers Support Group on campus, Jiménez says the work has introduced her to several mentor figures in her life including Bernardo Ávila-Borunda, assistant director of Campus Ministry.

The posters for the Dreamers group are vague on purpose, Jiménez says. The background is all black, and the sole image is a monarch butterfly, colored a brilliant orange and dotted with white. The only contact at the bottom is for Ávila-Borunda.

“(Ávila-Borunda) is a point of contact,” Jiménez says. “We don’t disclose who the other members are for the safety of the group. We don’t want to be open targets (for deportation).”

She says she feels safe talking publicly because of her DACA status. Jiménez received DACA before Trump’s cancellation of the program.

The butterfly on the poster is symbolic of the undocumented experience, Black says. “Butterflies migrate thousands of miles, crossing national borders on their journeys, and are powerful reminders that migration can be beautiful,” Black says in an email.

Jiménez says there are things at Marquette she wishes are better. One example of a needed change, in her opinion, is the assumption that everyone has the same legal rights.

“(Undocumented students) all get uncomfortable when we walk past a table and students say, ‘Hey, do you want to go study abroad?’” Jiménez says. “And obviously, I’m not gonna disclose my status right off the bat … but they keep shoving it in my face. I have to say, ‘Listen, I’m undocumented. I can’t go anywhere.’”

Jiménez worries if she goes abroad under the Trump administration, she will not be allowed back to the mainland.

There are still things that give Jiménez hope, though. Her privilege bracelet does have beads, after all.

“It’s tiny, but it reminds me: My family is intact. That’s a privilege. I can walk from one end of campus to the other end of campus. I’m bilingual — heck, that’s a privilege!” Jimenez reflects.

It is easy to feel overwhelmed as an undocumented student but it is also good to think of the small, positive things in life.

“Count the blessings that are there,” she says, smiling.

—————————————

Concern over underrepresentation in college settings is what pushed Marquette to strive for HSI status, Sergio Gonzalez, history professor at Marquette, says.

When Marquette first launched its HSI initiative in 2016, its undergraduate population was 9.7% Hispanic. As of the 2019 fall semester, the number has grown to 14%.

Full-time Latinx professors make up 4% of the faculty population at Marquette. That number, some argue, is alarmingly low.

“Institutional buy-in needs to come with resources,” Black says.

Once an institution achieves HSI status, it is eligible for federal Title V funds. Marquette is currently ineligible for Title V funding because its undergraduate Hispanic population has not yet reached 25%. Title V-funded training and research remains the only federal program to address social, behavioral and financial barriers faced by underserved mothers and children.

The grants are not limited to helping only Latinx students. Rather, designated HSIs typically use the money to improve broad curriculum development and student services.

“The resources that have been committed to this are not nearly enough,” Gonzalez says. “Really, all of the work that’s been completed is not because of the support of the administration, but in spite of it.”

—————————————

For underrepresented students, colleges and universities may seem exclusionary — a series of slammed doors and padlocks.

“Institutions will open the door and invite people in, but it’s almost like a halfway welcome,” Gonzalez says.

Gonzalez is Marquette’s first Latinx Studies professor. Latinx studies examines the cultures of Hispanic people living in the United States. By incorporating his Latino heritage into his teaching, he says he hopes to build community organically.

Gonzalez is a first-generation Mexican American and the first in his family to attend college. As someone with firsthand experiences of administrative hardships, he acknowledges how isolating the process can be for students.

“I see myself in the students who are first in their families to go to college,” he says. “They have a lot of weight placed on their shoulders.”

There are countless ways for mentors to provide support, Gonzalez says. If not in the classroom, then elsewhere — office hours, for example. He says he hopes to accomplish two main goals through one-on-one meetings and informal mentorship: to expand the number of diverse course options and to empower students to take charge of their own education.

Along with Ávila-Borunda and Black, he is a member of the Dreamers Support Committee Team.

“It’s the obligation of the faculty who have gone through that process and understand the experience very viscerally to step forward and serve,” he says.

—————————————

Over the past several decades, Wisconsin has experienced progressive growth in its populations of color. Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s largest metropolitan area by population, has become the most racially and ethnically diverse city in Wisconsin. Approximately 53% of city residents are racial and ethnic minorities, according to a study funded by the Greater Milwaukee Foundation.

The growth parallels national trends. By the 2031-32 academic year, approximately one in four high school graduates in the country will be Latinx, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education estimates.

————————————

When Marla Guerrero first began her college journey, she had no idea what a PhD was — let alone that she would someday earn one.

Guerrero, a mental health counselor and diversity coordinator at Marquette’s Counseling Center, was a first-generation college student. When she went away to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she was stuck navigating a complex system completely by herself. She remembers other Latinx students who faced the same challenges. Many did not make it down the aisle at graduation.

Looking back, she says she almost transferred, but she pushed through undergrad and she pushed through her Master’s program. And then came her doctorate in counseling psychology.

Guerrero chose to explore mentorship relationships for Latinx college students for her PhD dissertation.

“If it had not been for three women of color who became my mentors, I would not be here,” Guerrero says in an email.

Mentorship was a critical part of Guerrero’s success, she says. There were her work supervisors in undergrad — one was a director in residence life, the other a university administrator. They helped her reach out to a faculty member, who later became Guerrero’s mentor throughout graduate school. That faculty member provided Guerrero her first research experience, which helped her become a strong applicant for doctoral programs.

The dissertation took nearly three years to complete. Now, Guerrero wants to share her findings with colleges and universities so mentoring can be implemented with intention.

Jonathan Irias, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, says he does not feel supported by the administration; however, professors and faculty members have taken time away from their paid duties to help students like him.

“I have people like Marla. I have people like Jacki Black,” he says. “And this isn’t their job … but it’s the role they’re playing right now.”

Guerrero has a step-by-step process to mentorship. First, she says working one-on-one is key.

“If there is no trust, it can be difficult to truly help because students may not be comfortable to share with you what challenges them most. So … this process may take some time,” Guerrero says in an email.

Next, Guerrero says she tries to understand the individual needs of the students so she can connect them to resources.

“I work to ensure students follow up with either the things we discussed to do or check in to see if they connected to the person that I recommended,” Guerrero says in an email.

Because the process is inherently stressful for a mentee, Guerrero prioritizes mental health. She writes with a healthy mindset and supportive relationships, every student can have the opportunity to succeed.

“If every underrepresented student had even just one staff, faculty, or administrator who really showed their genuine care for them and believed in their potential to succeed, they would all cross that stage at graduation,” she says in an email.

————————————

For students who are undocumented, the path to a secure career may be met with distinct challenges. Careers requiring official documents — such as licensure and certifications — or out-of-country travel may be entirely out of reach. With DACA in limbo, the future is uncertain for hundreds of thousands.

Irias had only been at Marquette for two weeks as a first-year when DACA was rescinded. He says when he walked past some students, he could hear their taunts.

“You could hear, ‘Go back to your country!’ People were just walking by, yelling things,” Irias says. “I don’t really feel welcomed here.”

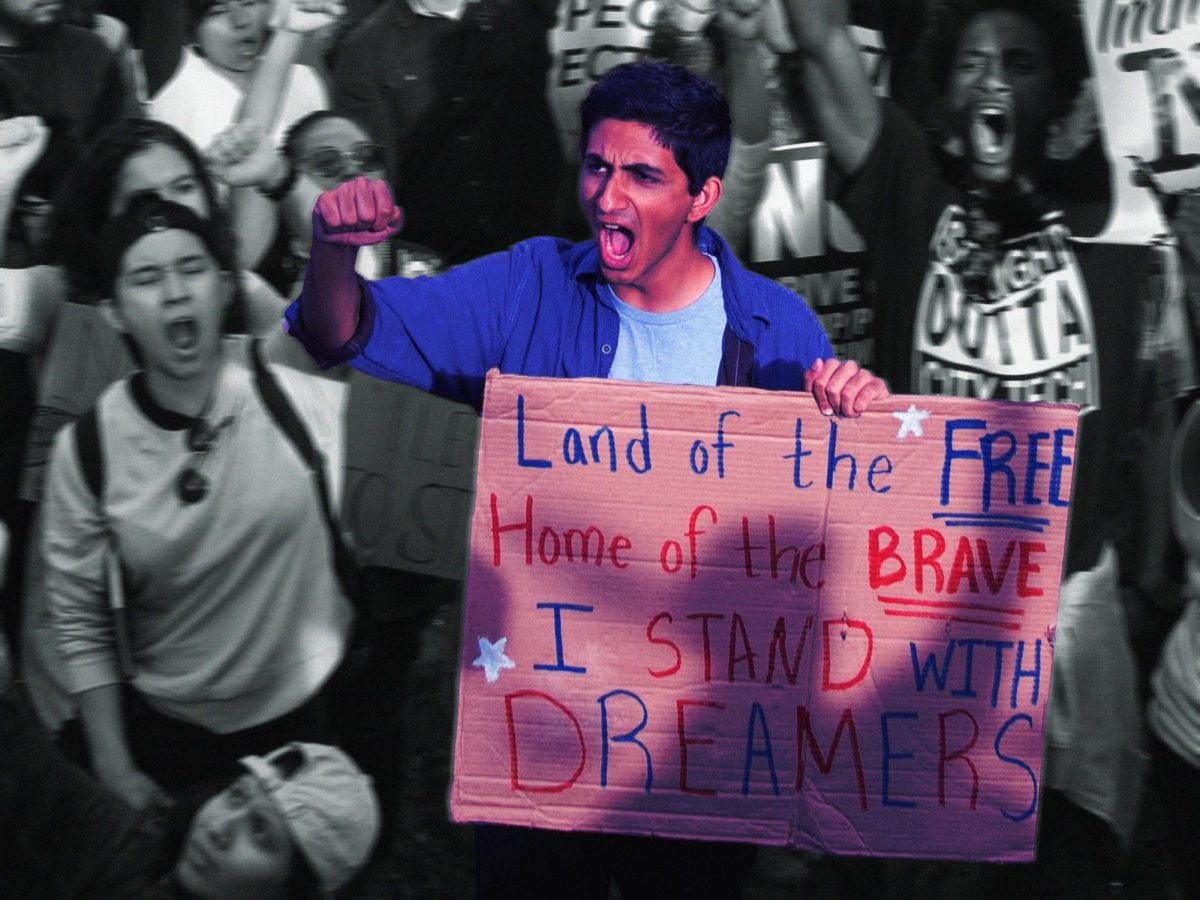

The 2017 motion to terminate DACA was met with immediate resistance. Immigrant youths and allies held protests nationwide. Several lawsuits were filed against the administration for terminating the program unlawfully.

Individuals who currently are or previously were DACA recipients can continue to submit applications to renew their status.

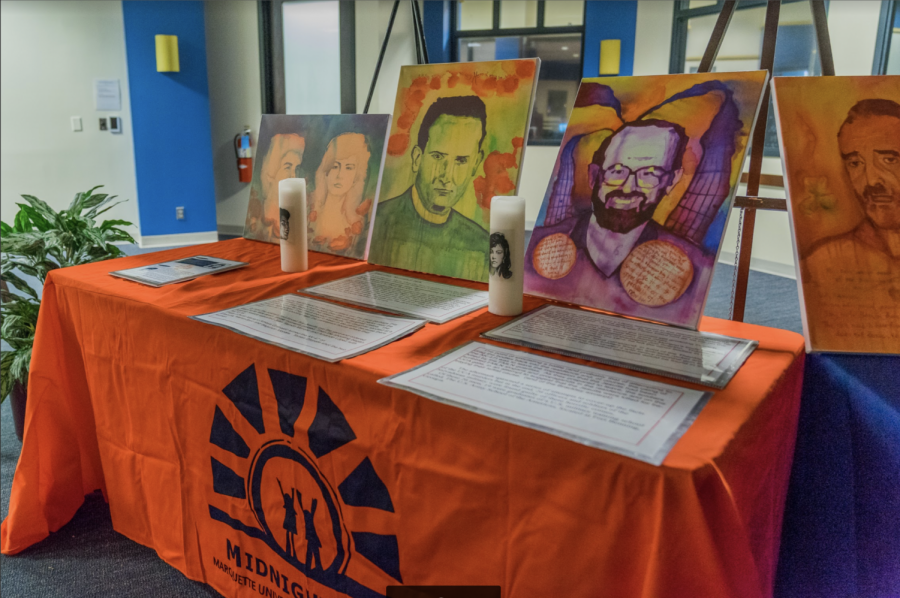

In 2019, Irias debuted an art showcase in the Alumni Memorial Union entitled “We Are Bright.” Photographs and audio recordings, collected over the course of several years, told the story of the undocumented experience.

“I attended protests and found people (to talk to),” Irias says. “The ultimate goal of the showcase was to show we are successful in this country.”

Irias is undocumented and part of the Urban Scholars program, a Marquette program which offers up to 10 annual, full-tuition renewable scholarships to underrepresented students. He is studying to become a lawyer.

————————————

Before he was brought on as a faculty member, Alberto Maldonado was a student at UWM. When he attended, the Roberto Hernandez Center was called the Spanish-Speaking Outreach Institute. He is now the interim director of the Center, a resource for Latinx students on campus. When he saw the center for the first time, he says it caught his immediate attention.

“Spanish-speaking? I’m gonna go there,” he says, smiling.

When Maldonado came to the U.S. from Puerto Rico in 1989, he says he spoke little English.

“I used to come to the center religiously,” he says. “It was the place where I could go get my paper grammatically corrected, or to just ask questions. It feels safe.”

Decades passed before Maldonado found himself directing the space. He says it is incredibly important for the RHC staff to reflect the population they serve. Each student-employee is bilingual, and several are first-generation college students.

“We know how many families are far more comfortable using their native language. We (hire bilingual communicators) with intention,” he says.

Of all the meetings Maldonado attends regularly, he says his favorite is not in his official job description.

Each Friday, Maldonado carves out time to meet with families who are looking to send their children to UWM.

“Students come in with a lot of questions and anxiety and they leave with a smile … understanding what the process looks like (gives them) hope that they can go to college,” he says.

————————————

There are some misconceptions about the process of becoming an HSI, Maldonado says.

“There’s this idea that once you announce you want to become a HSI, you’ll reach 25% overnight,” Maldonado says, snapping his fingers for emphasis.

The process can take years. For Maldonado, community partnership is what takes precedence.

“Even if we don’t reach 25%, the conversation we’ve entertained with the administration and across campuses is important,” he says.

Mentors help drive that discussion. At the Advancing Equity summit, Vice President of MATC Wilma Bonaparte, shared her story of mentorship: without the help of a Spanish-speaking professor, an understanding adviser and some kind students, she would have never been able to succeed in the U.S.

Through laughter, applause and some tears, Bonaparte concludes her speech with a quote by Dr. Seuss.

“Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot,” she reads. “Nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”