Martha Hennessy, granddaughter of social justice activist Dorothy Day, doesn’t like the word legacy.

“When people say to me that I’m following in Dorothy’s footsteps, that just makes me really nervous,” Hennessy said. “My family has been hit really hard with the whole legacy, and it’s not easy.”

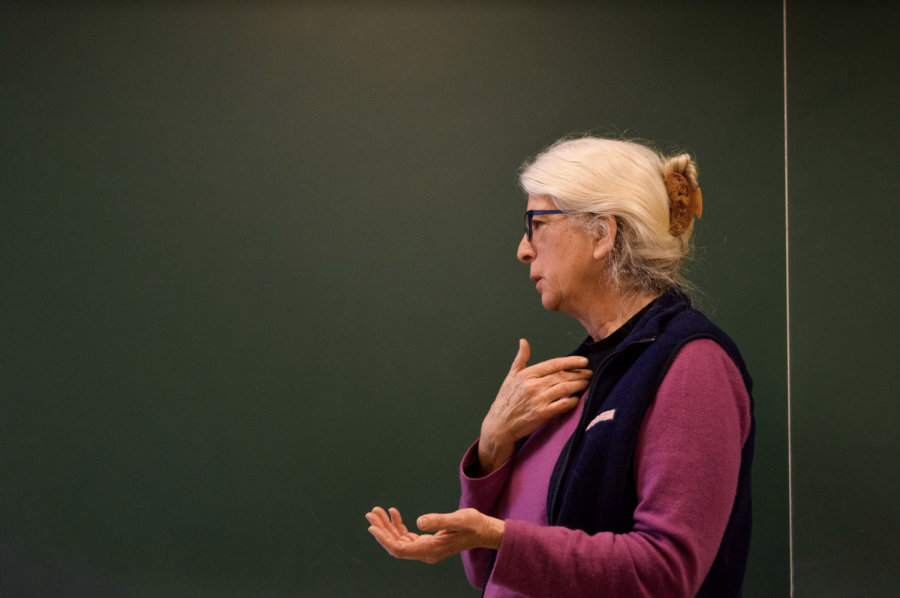

Hennessy visited multiple theology classes at Marquette Thursday. Visiting assistant professor of theology Karen Ross found out about the visit from David Mueller, cofounder of Dorothy Day Canonization Support Network, two weeks prior.

“I was so excited,” Ross said. “It’s a big deal.”

Hennessy also visited the Catholic Worker House in Milwaukee Thursday night.

Dorothy Day was a social justice activist and started the Catholic Worker houses and Catholic Worker Movement with her partner Peter Maurin.

Though Straz Tower doesn’t have the Dorothy Day Social Justice Living Learning Community anymore, the library still houses the Dorothy Day archives with her diaries and writings. Ross said Marquette’s archives are known across the country, and there is even a librarian in charge of archiving the files and talking about some of Day’s writings.

Hennessy talked intensely about her transition into activism and her grandmother’s journey of faith and her own. Day began as a journalist and converted to Catholicism later in life.

Hennessy spoke about Day’s devotion to the Catholic Worker Movement and her commitment to nonviolent resistance.

“(Day) was the head of a movement,” Hennessy said. “She had to go out and speak. She had to write. She had to bring in the people, the money. That was pretty significant for her. I don’t necessarily carry that burden.”

Hennessy, her eight siblings and her mother Tamar had left the church in the 1960s.

“It was a very difficult time,” Hennessy said. “I spent probably 30 years of my adult life trying to understand where I stood in terms of Dorothy’s intense conversion to Catholicism and my mother leaving the church.”

In 2002, Hennessy received a medal for Day, who had been inducted into the 2001 National Women’s Hall of Fame, which was postponed due to the events surrounding Sept. 11.

Hennessy said she had prepared a three-minute speech with the premise of invading Iraq would not be what Day would want.

“With that speech, I instantaneously polarized the audience,” Hennessy said. “It was in that moment that I gave that speech that I realized I had to come out. … With that event, I understood that my life would not be the same.”

After Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Rosalyn Carter showed their appreciation for Hennessy’s speech. Hennessy knew it was a necessity to come out and start advocating for nonviolent resistance, ending her career as an occupational therapist working with learning differences.

“We have created a system that just doesn’t allow for discernment, democracy,” Hennessy said. “The other thing Dorothy really made clear to young people was choose a vocation that doesn’t support the killing. That is a really hard thing to do. So much of our research and development is embedded in the war machine.”

Hennessy said how people live must reflect what they want to create in the world.

“How do we bring heaven to Earth? It’s not by preparing for war,” Hennessy said.

Hennessy stressed the importance of students reading alternative media and learning about these injustices outside of the classroom.

“Education is critical,” Hennessy said. “You’re going to have to educate yourself in ways that you’re not going to get (in the classroom). … You have to walk a line of being part of the establishment but not being so complicit that you lose your relationship with God and to each other.”

One of Hennessy’s points was that educational institutions do not teach enough about indigenous cultures. She posed the question, “How do we create a more multi-racial truly democratic society?” Though Hennessy emphasized that she doesn’t hate her country, she said apartheid is still prevalent today and has gotten worse over the past 20 years.

“We live in a white supremacy,” Hennessy said. “Things are very controlled. We can’t even begin to comprehend the realities of what goes on underneath the facade of our so-called democracy.”

After years of activism and numerous arrests, Hennessy and those who protested with her were convicted in October 2019 of 24 counts including conspiracy, duplicity and trespassing. The protesters broke into a naval submarine base in Kings Bay, Georgia, according to America Magazine.

They face up to 20 years in prison as a whole. The hearing is Feb. 9, and if the current ruling holds, Hennessy will spend 18-24 months in prison.

Meanwhile, Day’s first arrest was when she was fighting for women’s suffrage. Day never voted.

“Phil Berrigan had a saying: ‘If voting mattered, they would outlaw it,'” Hennessy said.

Hennessy said the beauty of what Day was trying to do was integrating mind, body, soul and spirit.

The way Day integrated all those facets of life was through her focus on voluntary poverty.

“Voluntary poverty subverts capitalism,” Hennessy said. “If you’re willing to not have the goodies held over your head to control you, and if you study journalism and if you have a real understanding of what journalism requires … you have to be willing to step out of (centralized media) risking your livelihood, risking your personal safety even, to report.”

However, Hennessy said this proves to be difficult for some today.

“It’s very hard, especially when you’re accustomed to the comfort,” Hennessy said. “We’ll have to be forced to give it up. Climate disruption is certainly one of those things that is going to force us to give up all of this … excess. We waste two-thirds of what we get. The globe can’t sustain that.”

Hennessy said Mueller plays a big role in Day’s canonization process. Mueller said he appreciates Day because of her advocacy for the unpopular opinion.

One of those unpopular opinions included her opposition to World War II and support of conscientious objectors. Out of the 30 Catholic worker houses in United States, Mueller said half closed because people disagreed with the stance and the other half went to war. According to Mueller and Hennessy, Day was the only Catholic leader in the 20th century that opposed every war from the Spanish Civil War on.

“For me, Dorothy Day, what stands out is her promotion of nonviolence and she opposed all the wars including World War II,” Mueller said. “She paid a great price within her own community for taking a stance.”

After Hennessy’s speech, Ross said her biggest takeaway from Hennessy was her speaking against governmental norms.

“Taking a look at how our governmental systems and the systems that we participate in, how we’re affecting the rest of the world and what call is ours as a Christian to do anything about that,” Ross said.

“What’s at the end of the road is the cross,” Hennessy said. “How many of us can actually say, ‘OK, this is what I’m going to do with my life?’ We can’t both pray for peace and bless the bombs, it’s very obvious.”

Evelia Guerrero, a junior in the College of Nursing, said the most impactful point Hennessy had was of finding the truths of the world.

“(That means) going into our community and being generally involved with our community because that’s where we see the issues, the hardships, but also the successes,” Guerrero said.

Ross didn’t know Day personally, but she said Hennessy has similar qualities in terms of her advocacy. Ross said the idea of radical nonviolence and ability to critique systems that are corrupt is a large part of Dorothy Day’s message.

“She’s not afraid to speak that even if it’s radical or can marginalize her. Dorothy Day definitely was very vocal. That’s a positive quality to not be afraid to speak the truth,” Ross said.

Father Joe Mattern, founder of a Catholic worker house in Omro, Wisconsin and former parish minister, said the answers lie in this generation.

“What is your attitude about climate breakdown and what are your hopes?” Father Joe Mattern said. “You’re the ones who are going to fill us with hope in our movement forward in doing something to this bad news.”

Even though Hennessy said her children will not be as involved in this type of activist work, she said God is the one who plants these seeds.

“Dorothy said, ‘The work will continue if God wants it to, it will continue. If it is good. If it makes sense.’ So we have to trust in that,” Hennessy said.

This story was written by Zoe Comerford. She can be reached at [email protected].