The University of Chicago recently became the most selective university in the nation to remove the requirement to submit an ACT or SAT score during the undergraduate application process. Marquette should consider instituting a similar test-optional policy, as this measure can be beneficial for students from low-income and underrepresented communities.

The number of universities with test-optional policies has grown consistently since 2005, with over 200 schools now participating. Marquette currently requires an ACT or SAT test score when submitting an application, along with a high school transcript and counselor recommendation.

Implementing a test-optional policy would be beneficial to Marquette’s diversity initiatives, a major focus of the current university administration. Institutions that have gone test-optional have increased the number of black and Latino students applying and being admitted to their programs, according to a study by the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

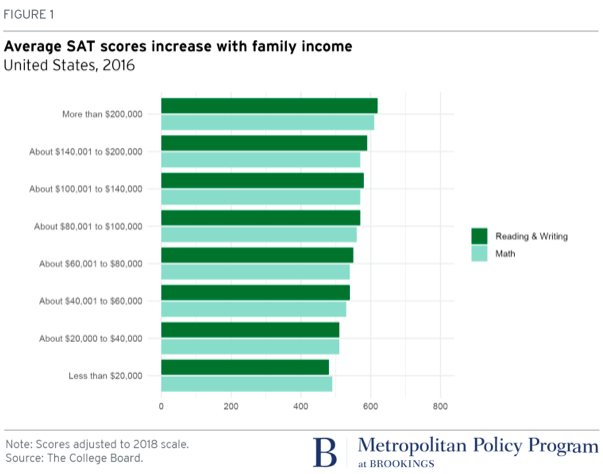

Students from these demographics are more likely to be economically disadvantaged, which plays a major role in testing success. ACT scores are correlated with income, as can be seen when reviewing the results from a 2016 ACT exam. Students who reported a family income of $80,000 or higher had an ACT composite score of 23.6 compared to a composite score 0f 19.5 from students who reported a family income of less than $80,000.

This disparity is partly tied to the high cost of test preparation services and tutors. A columnist for Vox stated that he makes up to $1000 an hour as an SAT tutor. Common tutoring companies like Princeton Review offer classes that start at $167 per hour of private SAT or ACT tutoring.

The tests are not always reflective of a student’s potential abilities in college, as they are meant to be taken in a fast-paced, focused environment. While quick test taking is beneficial for exam-intensive college majors, many liberal arts degrees are centered on essay writing abilities and projects. In these situations, students often have several weeks to formulate their assignments.

Instead of test scores, universities should put more focus on students’ grade point average and class rank. The difficulty of achieving high grades varies between high schools, but grades generally showcase a student’s discipline and ability to work with classmates and teachers. Four years of academic success should not be undermined by a three-hour test.

If Marquette considers removing the test requirement from applications, there will likely be fears of a decline in the quality of accepted students. However, the university can point to the success of students at test-optional schools like George Washington University and Wake Forest University as proof that not submitting a test does not limit academic success. George Washington University found that admitted students who did not submit scores had roughly the same first-year GPA as students who submitted scores, while Wake Forest University found that graduation rates are identical between the two groups.

For the policy to be successful at recruiting disadvantaged students, there would likely need to be an accompanying increase in funds for financial aid. When University of Chicago went test-optional, they announced full-tuition scholarships for students whose families earn less than $125,000 per year, along with a variety of other new scholarship options.

Marquette should consider making ACT and SAT scores optional, as this policy would indicate a continued commitment toward increasing diversity. It would also show that Marquette understands the ways in which test scores can be flawed measures at predicting academic success.