The Marquette University Police Department decided Motorola will be its body camera vendor, which means a departure from Axon, the vendor previously favored by the department.

The department already completed a three-month trial of the Motorola cameras with four officers and a shift commander. Capt. Katie Berrigan said officers preferred Motorola over Axon.

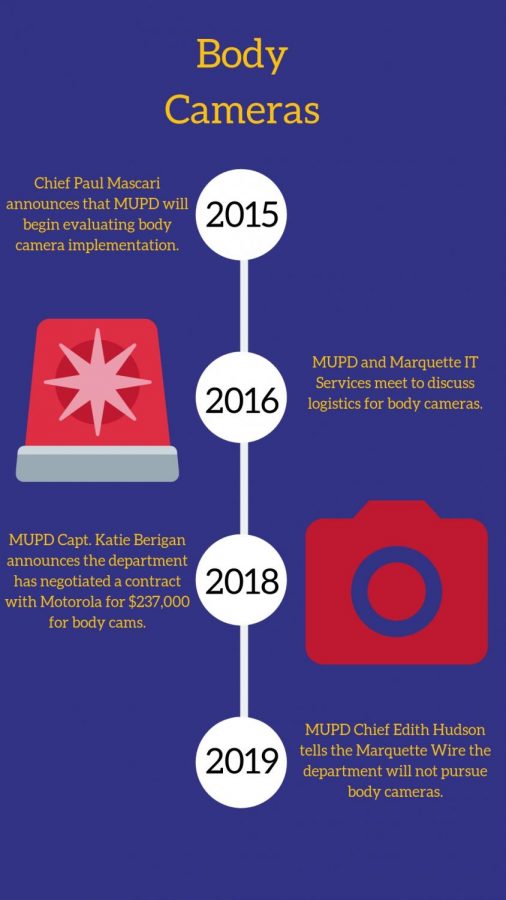

MUPD began looking to implement body cameras in December 2015, according to MUPD Advisory Board minutes. During summer 2016, the department tested Axon body cameras, but after being informed of changes in the company’s pricing, it began looking at alternate vendors.

The department previously favored Axon partly because it offered cloud-based storage for body camera data, but Motorola since developed its own cloud-based evidence management system, which Berrigan said was comparable.

The cameras and unlimited digital storage will cost $237,000 over five years. Hardware replacements every 30 months and technology updates are included in that cost.

Berrigan said MUPD plans to submit a budget proposal this month to fund the cameras. If that proposal is accepted, it would be for the 2019-’20 fiscal year budget, Berrigan said.

Jay Kutka, university budget director, said more detailed information about the funding process could not be provided, other than that any budget proposal requires vetting by senior university leadership.

Berrigan said nothing is confirmed yet, but if the proposal is approved, the funds would be available beginning July 2019. MUPD expects a fast rollout of the cameras, but Berrigan said the department does not want to rush the process.

Interim MUPD Chief Jeff Kranz said MUPD has a policy draft but will need to tailor it to the Motorola cameras’ specific design. The policy was modeled after both the Milwaukee Police Department and the Brookfield Police Department’s body camera policies.

Berrigan said the body camera program is a necessary step for MUPD to respond to public expectations of transparency in law enforcement.

Policy debates

Body cameras are growing in popularity across the U.S., with nearly all major U.S. city police departments equipping officers with the technology. In response to the trend, a coalition of almost three dozen civil rights, privacy and media rights groups published a set of principles for body cameras in 2015.

The principles address several policy issues, including when officers should record and whether officers should be able to review their footage to aid in writing incident reports. The coalition recommended the policies as a way to prevent corruption of the technology.

Upturn, a nonprofit technology policy advocacy group, began grading U.S. police departments against the coalition’s recommendations in 2015.

An updated scorecard for 2017 revealed that MPD satisfies only the first principle and either directly conflicts or fails to recognize the latter five criteria. In contrast, the Chicago Police Department satisfies four of the seven criteria and conflicts with only three.

None of the 75 police departments on Upturn’s scorecard met the criteria for limiting an officer’s ability to review their footage prior to writing incident reports.

Are body cameras effective?

In 2013, the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs predicted that the mere presence of the cameras would have a civilizing effect on both police officers and potentially combative citizens.

While the report acknowledged that body cameras cannot entirely eradicate excessive use of force alone, it predicted the technology would help to significantly reduce it. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Police Department Chief Joseph LeMire echoed this hope and said the cameras would benefit police-community relations.

“When people know they’re on camera, people present themselves better,” LeMire said.

A 2013 study by the Police Executive Research Forum seemed to validate these expectations.

It reported that use of force incidents decreased by 60 percent in Rialto, California, after equipping officers with body cameras. In Mesa, Arizona, eight months after implementation, officers wearing cameras reported 75 percent fewer use of force incidents than officers without them.

But more recent investigations into the uses of body cameras suggest they have not had quite the mitigating effect early research seemed to indicate.

In Washington D.C., a study conducted by The Lab @DC, an internal research team based in the mayor’s office, found no correlation between officers with body cameras and the reduction of use of force incidents.

The study acknowledged that the null result could be influenced by a variety of factors but that body cameras cannot dramatically reduce use of force incidents on their own.

Meghan Stroshine, associate professor of criminology and law studies, said there is a variety of reasons for the discrepancies between early research and The Lab @DC’s findings, including the difference in location, intensive use of force training in D.C. prior to the implementation of body cameras and the difference in the already existing relationships between police and the communities they serve.

The efficacy of body cameras comes down to individual police departments and how proactive they are in developing policies that address the potential hurdles involved in implementing any new technology, Stroshine said. Including officers in the development of policy could help to remedy misuse of the cameras, she said.

“When you adopt body cameras, there’s a learning curve for officers,” Stroshine said. “Officers should have more involvement in policy making so they have a better understanding of the rationales for when and why they should turn on their cameras.”

Despite their limitations, Stroshine said she’s cautiously optimistic about body cameras. She said the cameras will be beneficial as long as supplemental programs and policies are developed alongside the technology.

“We can’t rely on body cameras to be this panacea that’s going to fix everything,” Stroshine said. “Body cameras in and of themselves aren’t going to fix anything.”