When a topic becomes political, the first indicator is the language. The glossary of terms becomes a list of abstractions and jargon, used often, but lacking clarity or impact.

Diversity and inclusion are almost inherently politicized terms: used in public addresses and mission statements, but rarely exemplified by those touting the language.

At a point, the rhetoric we use in Marquette Wire editorials becomes as inundated with buzzwords and abstractions as the language we criticize the university for using. So, to put it plainly, without the contentious terminology: Marquette should employ more faculty of color.

If members of the Marquette community were to believe the language used to describe the university, they may be under the impression that Marquette is less white than it is.

The President’s Task Force on Equity and Inclusion, the climate survey, the initiative to become a Hispanic-serving institution and the Center for Intercultural Engagement are each efforts on the part of the administration to acknowledge the need for a diverse campus.

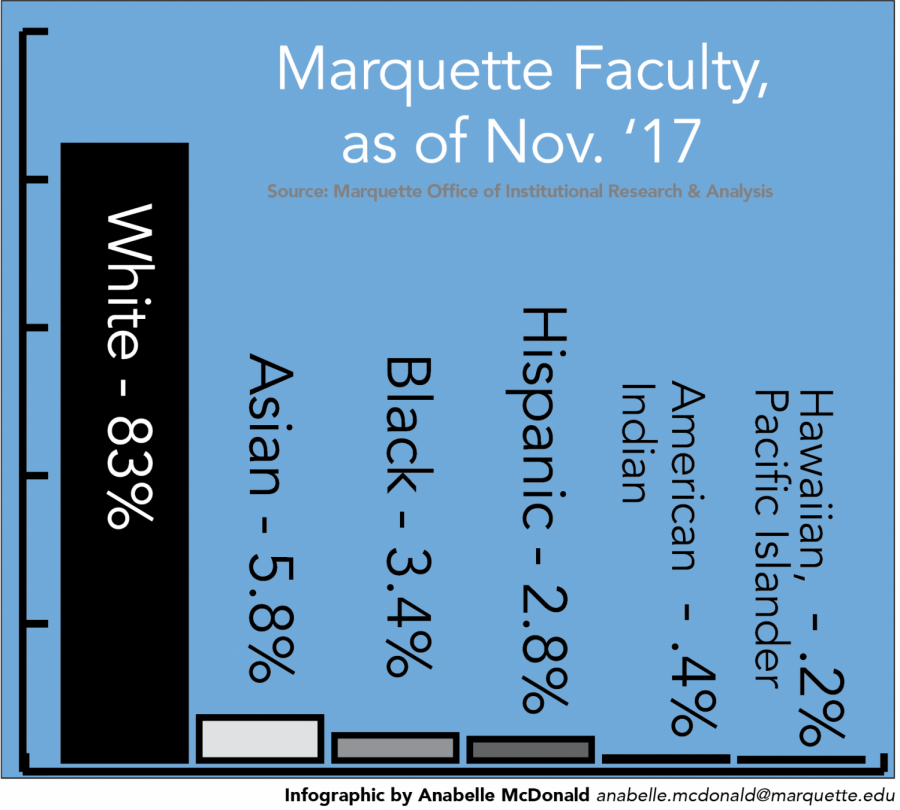

In November, 163 of Marquette’s more than 1,200-member faculty were nonwhite, according to Marquette’s Office of Institutional Research and Analysis. This is a one percentage point increase from fall 2013.

Currently, 3.4 percent or 42 of the more than 1,200 Marquette faculty members are black. In the U.S., African Americans account for more than 13 percent of the population.

Five-point-eight percent of the faculty are Asian, 2.8 percent are Hispanic. All other racial minorities each make up less than half a percent of Marquette’s faculty.

More than 1,000 of the 1,220 member faculty, or 83 percent, are white.

Marquette is not the only institution that employs few minority faculty. This has been an issue in higher education since the civil rights movement. But, given Marquette’s affinity for progress, university leadership should be eager to break from the status quo.

It is important for young people to see themselves in positions of authority, for the same reasons it is important for them to see themselves in popular culture, sports and politics. So, when a university doesn’t hire faculty of color, it is telling its minority students that there is no place for them in the professional world.

Conversations about diversity almost always devolve into conversations about affirmative action and merit-based admissions. While the faculty hiring process is much different than undergraduate admissions, the root problem is the same: Lack of opportunity disproportionately affects students and professionals of color.

University spokesperson Chris Jenkins said in an email that Marquette has developed a “strategic process to address this challenge.”

“As part of our strategic plan, we have emphasized changing the culture for faculty hiring processes and establishing more accountability,” Jenkins said.

It is important to recognize efforts by the university to improve, and it would be unfair to say that noone at Marquette is working on this problem. But there has been a one percent increase in minority faculty over four years. There comes a point when even the most optimistic have to acknowledge that whatever effort is being made is ineffective.

At the University of California at Davis’ law school, 56 percent of the faculty are people of color. As the law school’s dean, Kevin Johnson, has said, they got there one hire at a time.