President Donald Trump signed the largest tax reform bill in 30 years Dec. 22. The bill passed the House 227-203, with 12 Republican representatives voting against the bill, and passed the Senate 51-49, with no Republican senators voting against the bill.

Large tax reforms don’t come around every decade, so Americans can expect to live with this tax code for years to come. For millennials, this means becoming situated with the new laws while going to school, getting first jobs and buying first houses or first cars.

University spokesperson Brian Dorrington said the university is pleased the bill maintains provisions that directly benefit Marquette students.

“We understand and appreciate that the cost of a Marquette education is a financial sacrifice for many of our students and their families,” Dorrington said. “So while these provisions were only a small part of the overall proposed legislation, their importance to the Marquette community cannot be understated.”

Here’s what students stand to gain, keep or potentially lose from the new tax bill:

1) Tuition waivers remain in place

Masters and doctoral students, who have at least part of their tuition paid by working as teaching or research assistants, do not have to pay taxes on the amount they earn. The money from the university paid toward students’ tuitions in exchange for their work cannot be considered part of the students’ incomes, as was proposed in the bill.

Marquette students, for example, would have had to pay taxes on the amount they receive for the Pere Marquette award that goes toward paying their tuition.

If the money the university is using to pay students’ tuitions was considered part of the students’ incomes, the students would be stuck paying potentially large amounts of taxes on university money.

In November, faculty said they feared this could deter students from seeking graduate degrees at a time when graduate students are already in short supply.

2) Employer tuition assistance remains non-taxable

Employers can contribute up to $5,250 per year to an employee’s tuition for continuing education programs.

Keeping employer tuition assistance non-taxable is a win for employers looking to help their employees gain new degrees and expertise.

3) Student loan deductions stay the same

Graduates can claim up to a $2,500 deduction off their taxes each year for interest paid on their student loans. However, that provision phases out as graduates’ incomes increase.

4) Potentially lower income taxes

Typically, young people have less money than their older counterparts.

For many young adults who don’t make large figures, they may be put in lower tax brackets.

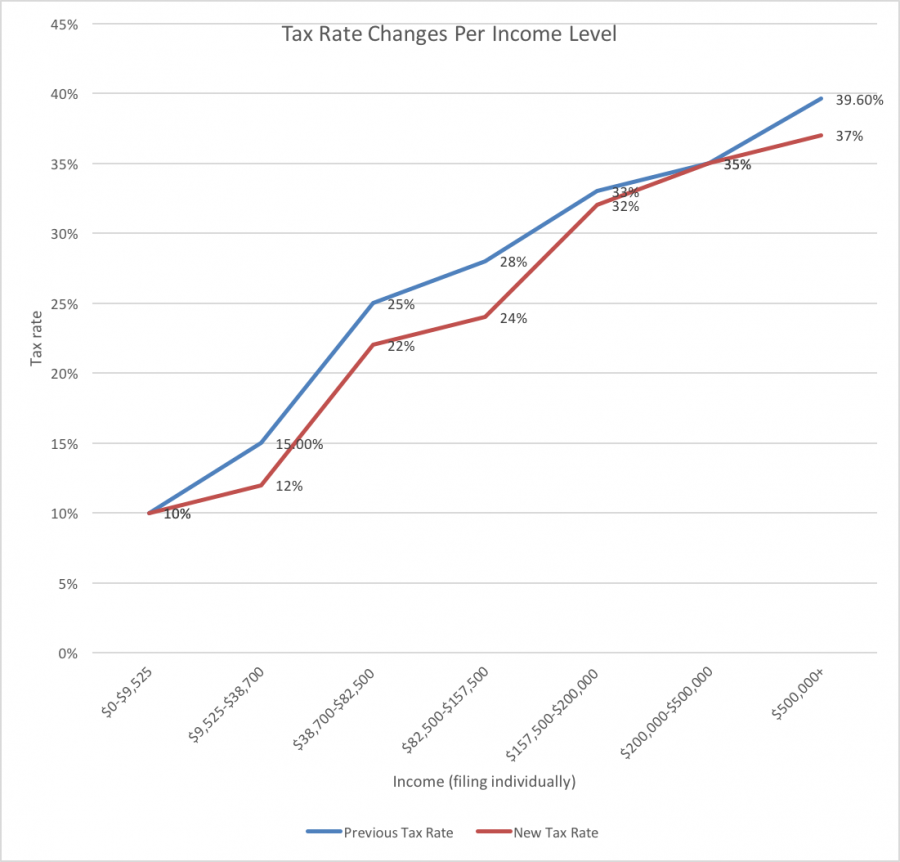

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the median weekly pay for people between the ages of 24-34 is $778. That adds up to around $40,000 per year. An individual making that amount would move from a 25 percent tax rate to a 22 percent tax rate.

For millennials in that bracket, that would mean average savings of over $1,000 yearly in take-home pay.

James McGibany, a professor of economics in the College of Business Administration, said that graduating students will likely face lower tax rates than their older siblings and friends did in the recent past.

“For example, as long as one’s salary is above about $9,500 and lower than $200,000 (for single filers), the tax rates faced are now a bit lower,” McGibany said.

But those provisions lowering tax rates expire in 2027, as they were not made permanent by the tax bill. In 10 years, anyone making less than $75,000 will see a tax increase. It is possible that many of today’s students will fall into that salary range within a decade as they see raises and promotions in their jobs.

5) Potentially higher incomes

Republicans promoted the bill with the concept that cutting the corporate tax rate would allow businesses to raise employee salaries with the money saved.

However, that can not be enforced or guaranteed by the bill. It is left up to the corporations themselves.

A handful of large companies such as AT&T, Boeing, FedEx and Comcast said they will use their savings to increase wages for lower level workers, according to a report from CNBC.

The corporate tax rate was cut from 35 percent to 21 percent in the bill.

The question of whether more firms will follow suit can only be answered on an individual basis in the coming months and years, which is why – for now – higher incomes can only be speculated on.

6) Health care mandate repealed

A provision to remove the health care mandate was included in the tax bill, which means there is no tax penalty for being without health care.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated around 4 million fewer people will have health insurance in the year following the tax bill being passed. As a result of people choosing not to have insurance because they don’t have to pay a tax penalty for it anymore, 13 million people are estimated to be without health care by 2027.

“Given that younger folks who might make take the choice of no insurance tend to be healthier than older workers (less in need of health coverage) – this means, on average, those now covered by health insurance are a bit less healthy,” McGibany said. “This means one would expect health insurance rates to rise a bit, whether you buy it individually or the amount you pay in to be covered as part of your job benefits.”

Premiums should rise by about 10 percent for those with healthcare, and there is projected increased government spending on emergency room trips and doctors visits for those without healthcare who need to go to a hospital.

Thirty-six percent of people enrolled under the Affordable Care Act are under the age of 34, according to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid services, which is tasked with overseeing the ACA.

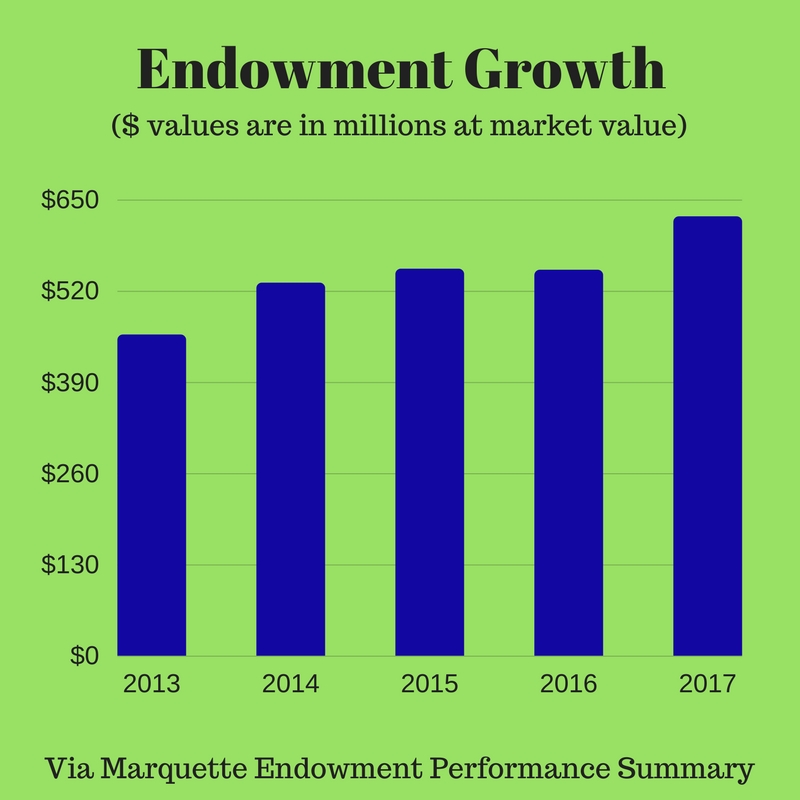

7) Potentially fewer donations going to universities

There is less of a tax incentive for charitable giving, such as donating to a university, professor of political science Duane Swank said.

Tax cuts mean less revenue for the government, but which federally-funded programs will take the hit is unknown.

“Indirect pressures come from problems created for state education spending when many people can no longer deduct all their state and local taxes and hence begin to push against high state taxes – which (sic) fund public university education,” Swank said.

A majority of the effects of the tax bill won’t be evident for a few years.