My grandma defends the sanctity of a family meal with the decree, “We don’t talk about politics at the dinner table.”

I know this rule is less about maintaining civility, and more about protecting me from what would otherwise be an anti-liberal firestorm by the more outspoken, so-called conservative family members at the table.

My grandma has always been very patient with explaining the intricacies of partisan loyalty to me even when, after spending a summer with my mom, I returned to her table with the impression that Republicans were bad guys.

She was never one to initiate political conversations, but when I asked questions, she’d do her best to help me understand. Some of the most profound political discussions I’ve ever had have been while eating an after-school snack on my grandma’s living room floor.

My grandma summarized her explanations with the idea that it doesn’t matter what I believe so long as I do my best to be a good person. It was comforting, and has remained with me in the years since.

My next exposure to partisan politics was far less comforting and took place during a high school civics class. Most of the class was unsure of the distinctions between “liberal” and “conservative,” and we were given a personality test that would help determine our respective affiliations. By the end of the questionnaire I’d been picked up and branded the nondescript “liberal,” while many of my peers were pushed with equal force and lack of explanation into the branding of “conservative.”

But now I have to wonder, do we devote ourselves to dogma consistent with our branding because we actually believe it, or because a quiz we took when we were 16 told us we do?

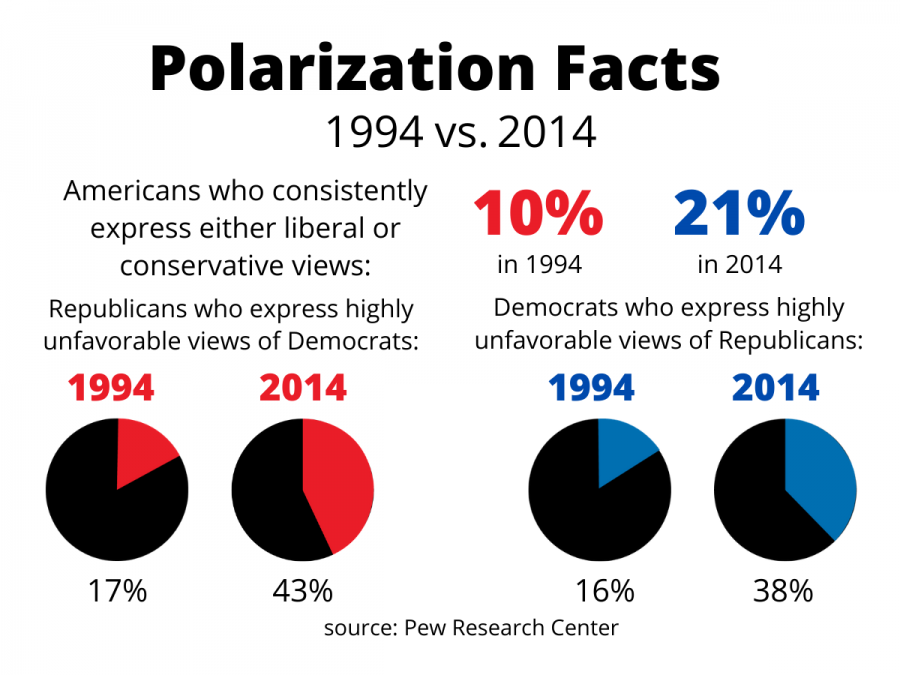

The categorizations are given slight impetus by increasingly partisan news commentary and the social media militia (on both the left and right), but my experience with partisan politics is that a lot of the values we claim to champion are more centrist than we’ve been told.

We all want the best for our country and its people, and while we may occasionally disagree about the means to the end, party separation has created the illusion that our goals are opposite.

I’m not accusing anyone of groupthink, but if we’re not asking ourselves which of our values coincides with a particular policy or politician, we’re admitting complacency with being told what to think. If that’s the case, the question isn’t even about policy, it’s about association.

Socially traditional ideology is lumped with conservative politics, and socially progressive ideas are dubbed politically liberal, and while there’s obvious overlap between the given categorizations, our politics should not be contingent on our backgrounds.

Assuming that an entire demographic would all feel the same way about a particular topic neglects obvious intersections in racial, gendered and socioeconomic positions.

I know middle-aged white men who ride around in camouflage pickup trucks who support a path to citizenship for undocumented persons and I know minority women living in urban environments who donate money to the National Rifle Association. Belonging to one group does not necessarily exclude you, or oblige you, to another.

Blanket statements against “liberals” or “conservatives,” as are popular among politicians and media personalities, assume the audience fits one of only two categories, and it’s frustrating to be so easily pigeonholed.

I hesitate to make an operatic claim comparing partisan politics to a civil war, but it’s hard to ignore the existence of an explicit divide in our country’s social climate.

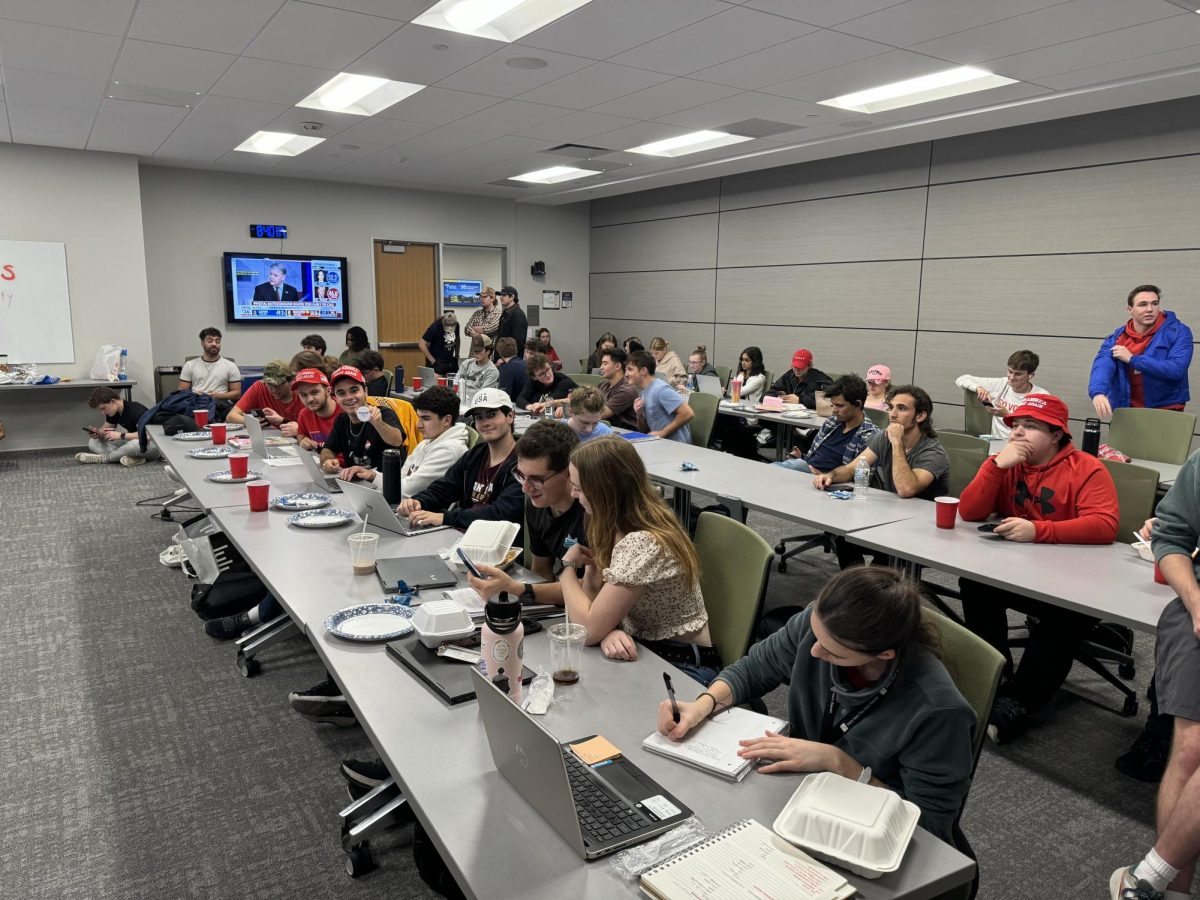

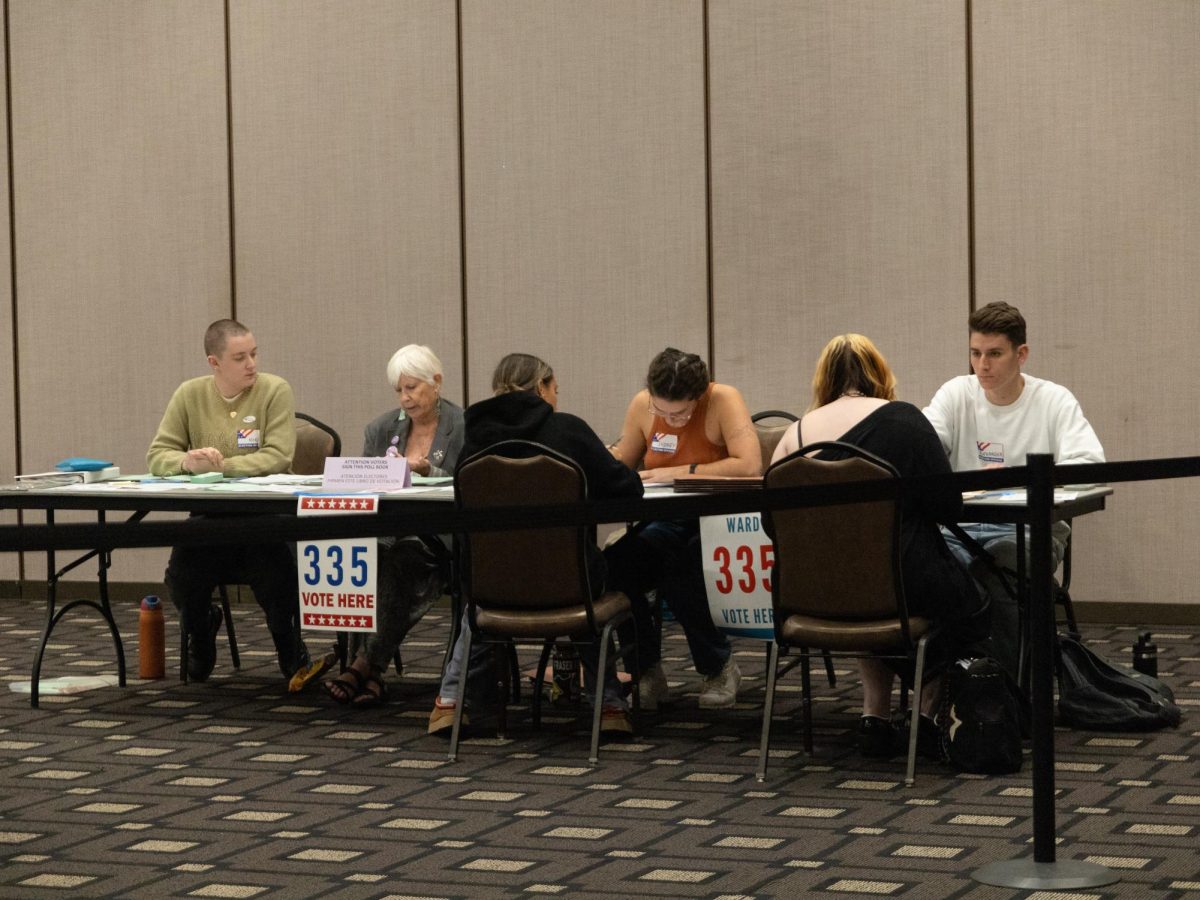

Being that we’re in the midst of an election that, so far, has come down to hard-line party loyalty, we all owe it to ourselves and to our country to really consider which candidate’s platform aligns best with our own set of values.

We can’t afford an election determined by followers.