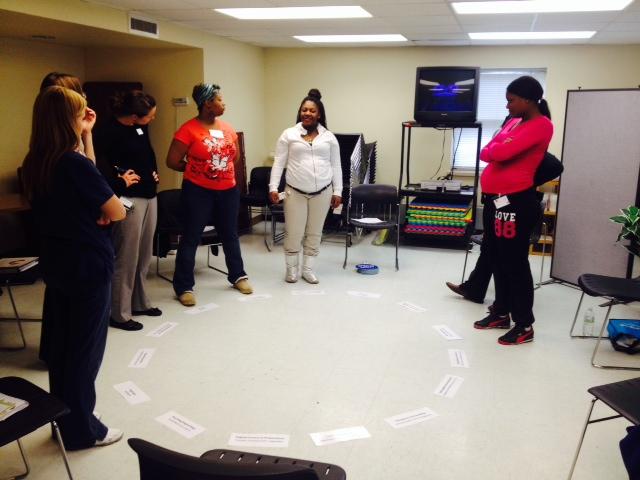

Six expectant mothers sit in their Centering Pregnancy group in the Marquette Neighborhood Health Center discussing the topic of the day: domestic violence.

One of them breaks down, sharing her fear of her abusive partner. She already has one child and does not know what to do with another on the way. Immediately, a group member rushes to help, giving the woman her phone number and address. She offers to let the threatened woman stay in her home for the rest of her pregnancy.

Such stories are common at the College of Nursing’s MNHC, where women learn how to take care of themselves and their children throughout their pregnancies. Yet, as the center reaches the end of its five-year grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, some fear it will be forced to close.

“We are doing great work and just need more patients to drive down costs,” said Andrea Petrie, director of development in the College of Nursing, in an email. “Additionally, we are primarily a Medicaid clinic (80 percent), so we are only receiving 25 percent reimbursement for many services. This makes the clinic difficult to sustain without benefactor support.”

MNHC has provided health care and pregnancy support to a patient population that has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the country since it opened in 2007. Its services are also available to Marquette faculty and students, though a recent relocation moved it further into the north side of the city, where most of its clients are from. According to the College of Nursing, 79 percent of the center’s patients live in the city’s poorest ZIP codes.

The women are also young. The average age of a patient is 23.7 years old. Seventy percent are African-American, a race with a rate of infant mortality three times higher than that of whites in Milwaukee.

MNHC’s case manager, Heather Saucedo, explained that this gap is not caused by genes. Research suggests the danger is in a mother’s stress causing her to go into pre-term labor.

“What (researchers) think it comes down to is racism,” Saucedo said. “That contributed to high levels of stress and high levels of stress … can trigger your body to go into pre-term labor. If these babies are born too early they can’t survive a lot of times.”

The patient population at MNHC is vastly different from the people most Marquette nursing students work with during their rotations in a city hospital. Nicolette Mendoza, a senior in the College of Nursing, was one of the two students who did a rotation at the center last semester.

“I definitely thought it was a unique experience because the clinic primarily serves under-served women,” Mendoza said. “A lot of them are low-income. They don’t live in the best neighborhoods, they don’t have good support systems. It was eye-opening to see some of the conditions people live in and what they’re going through.”

Mendoza, like the other students who chose to learn at the center, accompanied Saucedo to the homes of clients. She said she was able to visit neighborhoods that she would not have gone to otherwise and see the struggles that some community faces.

Some of the houses she visited were rundown and crammed with people – a stark contrast, she said, to her own middle-income upbringing.

These are the people Saucedo works with for hours almost every day. She said it is sad that even some nursing students do not know MNHC exists.

“It’s a totally different patient population here,” Saucedo said. “A lot of times they’re late. Sometimes it’s no shows, canceled appointments because they just have a lot of life crises going on. That helps (students) have a little bit of compassion.”

The center continues dealing with challenges, including funding, gaining more patients and attracting more students. Still, the work of the small staff has helped MNHC reach a pre-term birth rate of 3.75 percent, compared to 12 percent, nationally.

A new crowdfunding effort is working to reach $250,000 by June 30 and Petrie said maintaining the center is a top priority for the college. MNHC CNM Service Director Kathlyn Albert also wants more students to have the opportunity to gain experience there.

“Part of the problem is space,” Albert said. “But I think we can do better to help students get even a one or two day experience. It’s a work in progress.”

Working at the clinic gives students more than just nursing experience, Albert explained. The work can even involve helping clients find jobs, get their electricity turned back on or get their baby’s birth certificate. Much of the work is one-on-one with patients and the center prides itself on giving clients plenty of time with the nurses and midwives. The work is aimed at helping mothers stay healthy and get every resource they need to take care of their children and themselves.

“We all live here in this community,” said Saucedo. “If you live in a community, you should be at least somewhat engaged in your community. Even if you’re just here for a short time, like Marquette students, you do want to live in a healthy community. We’re all a part of it.”