This university is constantly under attack. The prize at stake: the identity of its students.

Justin Webb, Marquette’s information security officer, has overseen the university’s cyber security since 2010.

“We haven’t had ‘the breach’ yet,” Webb said. “But our network is attacked 24 hours a day by anybody and everybody — and by attack I mean it’s being scanned. People are trying to break into things. So that’s where all our defense mechanisms come into play.”

University data centers are treasure troves for hackers. They hold thousands of pieces of private information like social security numbers, financial records and intellectual property as well as in-process credit card transactions, a potential jackpot for cyber thieves if they can identify and exploit a vulnerability in any stage of the process.

Protecting this information is becoming a central concern for universities as institutions increasingly come under attack, facing millions of threats weekly.

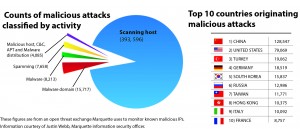

The constant barrage is typical, especially for large research institutions. The University of Wisconsin-Madison reported receiving 90,000-100,000 cyber-attacks a day in 2013, primarily from Chinese IP addresses.

At least 3 million people had personal information that could be used for identity theft exposed through an educational institution last year, according to the Identity Theft Resource Center, which records publicly announced data breaches. That number may be a low estimate as schools that have breaches often do not report the number of people affected and many breaches are never detected.

Two exceptionally large breaches at universities stand out. In 2010, a breach at Ohio State University exposed 750,000 names, Social Security numbers, dates of birth and addresses. Photo IDs of 60,000 former student with Social Security numbers and names were hacked from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2010.

More recently, though, St. Louis University, a Jesuit school of a comparable size to Marquette, experienced an attack in which 3,000 health records and 200 Social Security numbers of students and staff were exposed in an email phishing scam.

On top of the risks of exposing student information, security breaches cost schools millions. In November 2013, the Maricopa County Community College District in Phoenix, Ariz. reported a data breach that exposed information of about 2.49 million people associated with the district’s 10 colleges. The breach cost an estimated $14 million to cover services such as credit monitoring for people affected by the breach.

WHY ARE UNIVERSITIES TARGETED?

Schools may become targets for hackers because they have important data and can be easier to access than businesses.

“As businesses are locking down, hackers go after the next easiest target of opportunity,” said Bruce Boyden, a professor at Marquette’s Law School specializing in privacy law.

Boyden noted that this is a challenge for educational institutions, which are not used to taking the steps of securing confidential information.

“A university is supposed to be an open exchange of ideas, the ideal of the academy,” he said. “So it’s antithetical to their nature to lock down information, but I think that universities are going to become more and more of a target for attacks to get access to their databases of student information. It’s something universities need to be thinking more about.”

Schools are also made vulnerable by using new, cutting edge technology that is less vetted for security risks. IT professionals in higher education additionally wield less control over campus web traffic which adds another obstacle for security.

“You can walk onto campus with any device and connect to the wireless network as long as you have a login,” Webb said about Marquette. “So it creates this sort of Wild Wild West for security.”

Webb explained that Marquette does not prevent students or staff from going anywhere with its network, and it does not have the content restrictions for inappropriate sites standard in most corporations.

“That’s a good thing for academic freedom and research, but that’s a bad thing for me because those sites end up infecting people,” he said.

CYBER SECURITY AT MARQUETTE

Webb tries to avoid vulnerabilities in Marquette’s system and looks to eliminate “low-hanging fruit” that allow hackers to obtain valuable information because a system is configured incorrectly. There is too little oversight of students or staff who fail to update their computers or willingly give out information exposing them to attacks.

Every day new security flaws are discovered in hardware and software. Hackers use these flaws, often minutes after they are discovered, to infiltrate systems and bypass security controls.

“It’s a constant battle because security is always evolving,” Webb said. “So once you knock out one threat, something else comes along. As technology advances so do hackers. As hackers advance so do defenses … The old saying goes ‘You don’t necessarily need to outrun the bear, you just need to outrun everyone else the bear is chasing.’”

Webb communicates with a network of information security professionals who share developments and attempt to create patches for the system flaws hackers manipulate.

“The most important thing for me to do is to think like a hacker,” Webb said. “I have to think of the worst possible outcome and then hope what I’m testing has been engineered correctly so those nefarious scenarios cannot occur. The more you can think like a bad guy and test that stuff out, the better you are at securing it because that’s how bad guys think.

“It’s not all roses sadly, and I’d say it’s getting worse in general,” he added. “It’s not getting better.”

Phishing emails are also common at universities. IT professionals at Marquette follow phishing scams that come into the university closely and can block IP addresses from senders, report and disable malicious attachments and track when students or staff have clicked links or opened attachments that can harm their computers.

Phishing emails can vary in severity and the university responds differently to the scams accordingly.

“There’s very nonspecific phishing where there is a lot of misspellings and it is blatantly not legitimate,” Webb said. “But when it gets to the point where it starts mentioning the university’s name and the page looks like a university page, that’s when we’ll start sending out notifications.”

A TOASTER VENDETTA

While there have not been any large-scale breaches at Marquette, the campus did see an internal malicious cyber crime in 2012. It was a small-scale hack done to avenge a lost toaster.

The incident made news when on Jan. 30, 2012 a now-former Marquette engineering student and IT technician, Christopher Cichon, installed a keylogger on a Marquette residence hall official’s personal computer, according to a Milwaukee County criminal complaint.

The official had confiscated Cichon’s toaster, which is prohibited in university residence halls. Seeking retribution, Cichon donned the guise of setting up a printer on the official’s computer to install a keylogger called KidLogger. For one week the application allowed Cichon to access screenshots and keystrokes from the computer secretly.

He later told law enforcement his plan was to “post things to get back at her.”

Cichon withdrew from Marquette in February 2012 and pled guilty to computer crime. He was sentenced to 90 days in prison and one year probation that would include community service, anger management, a $500 fine and a requirement to “write an essay on how people can avoid being a victim of computer hacking after watching the movie ‘Network,'” according to court documents.

Brian Dorrington, senior director of university communication, said in a statement the school “takes any allegation of misuse of technology extremely seriously and monitors all aspects of its information technology systems. No university databases or servers were affected.”

Webb was responsible for the university investigation into the attack after the Department of Public Safety reported a suspicious email the official received.

“It’s like trying to find all the crumbs to put the cookie back together,” Webb said. “So in this case (Cichon) was using a specific type of keylogger and spyware so what I looked for was any computer in that area that had accessed that IP address. There were only two and it ended up being the offending computers, so once I found that I could look to see who logged onto those computers, and it snowballed from there.”

Webb finds the incident to be a testament to Marquette’s security system’s ability to root out malicious activity.

“Though it was unfortunate that it occurred, it was also good that we found out who it was,” Webb said. “It lets you know that if you were a victim of a crime that involves a computer you could come to us.”

RESPONDING TO CYBER CRIME ON CAMPUS

When Marquette’s information security incidents break laws as in the Cichon case, Webb turns his investigation over to law enforcement.

“I’ve worked with DPS, I’ve worked with the Milwaukee Police Department, the FBI, and there are multiple resources we can go to in those cases, but it doesn’t rise to that level, nearly ever,” Webb said.

In most cases security incidents don’t require criminal investigations. Generally, Webb and other university staff simply meet to discuss the incident, figure out how it occurred and make a plan to ensure a similar problem does not happen again.

But Webb said much of his attention is focused on prevention rather than investigation.

“I try and do security in a sort of proactive sense and not a reactive sense,” Webb said. “Any application that you ever log into, I’ve gone through and checked the security of it. We also do all sorts of audits on our systems. I run so many (protections) I can’t keep my head on straight.”

But despite the security entities in place, recent well-publicized data breaches at companies like Target and Neiman Marcus reveal that even institutions with protections can fall prey to attack.

“At Marquette, we are lucky because we do have very good review processes and monitoring tools to help keep things secure,” Webb said. “But when it comes to things getting through the system, it’s not really a matter of if, it’s more a matter of when.”