Concussions have repeatedly been brought to the forefront of the controversy over sports-related injuries, given recent events in both the National Football League and the National Hockey League. In its second installment of the Marquette Presents series, the College of Health Sciences hosted a panel to cover the medical, social and legal effects of concussions.

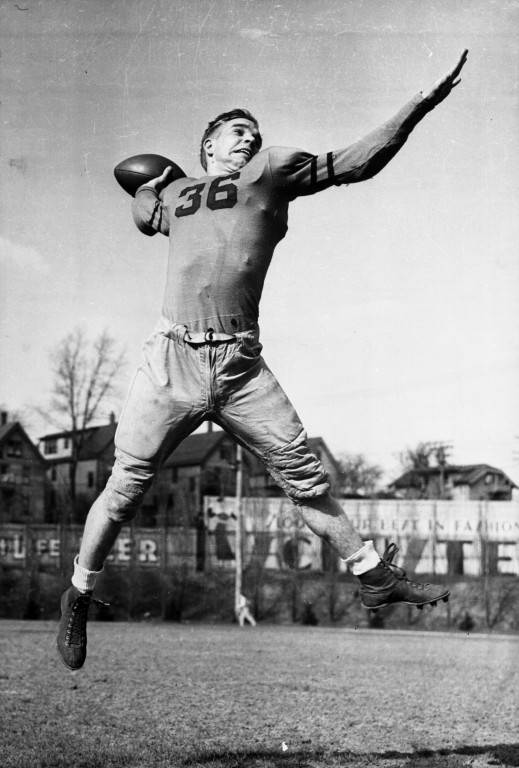

George E. Koonce Jr., a Marquette director of development and a former National Football League linebacker for the Green Bay Packers, was among the featured speakers at the event.

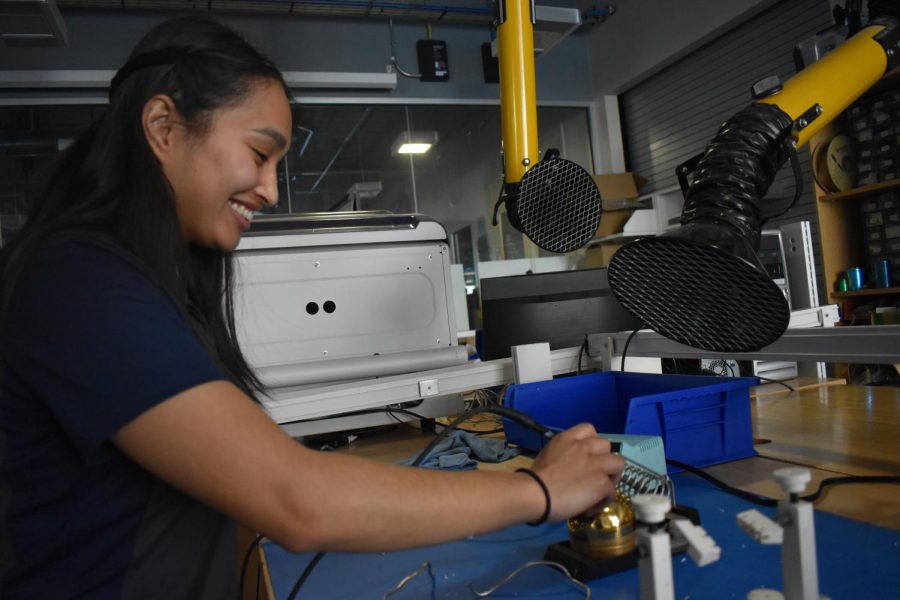

Other speakers included Michael McCrea, a professor of neurosurgery and neurology at the Medical College of Wisconsin; David Leigh, a clinical assistant professor and athletic trainer at Marquette; Carolyn Smith, director of Student Health Services and Matthew Mitten, a professor in Marquette’s law school and director of the National Sports Law Institute all presented at the panel discussion Monday in the Alumni Memorial Union.

“Everyone has been told that a concussion is a bruise on the brain,” McCrea said. “That was thrown out the window many years ago. This is an injury that happens at a microscopic cellular level. This is an injury that occurs by the virtue of a mechanical force causing disruption of normal neuronal activity.”

Koonce said that whenever there were challenges confronting the sport, the leadership stepped up to make sure students and professional athletes were accommodated. In contrast to Larry Williams’ recent comments in On the Issues, Koonce’s statements were quite optimistic.

“I think football is a part of our society,” Koonce said. “It’s a part of our fabric. Not just football but sport. Americans truly, truly love sport. It gives you so much. It brings families together, lets you learn a little bit about perseverance, lets you learn a little bit about communication.”

Koonce and other panelists agreed the most important thing athletes can do when it comes to recovering from concussions is to take time off from playing.

McCrea said that 80 to 90 percent of athletes take seven to 10 days to recover from a concussion, while the remaining 10 to 20 percent take up to 45 to 90 days for a full recovery. He said that 75 percent of all repeat concussion happens within the first seven days, and 92 percent occur within the first 10 days after receiving the first concussion, so sitting out is the only way to assure a player’s recovery.

“One of my pet peeves is if you’re injured you can’t play,” Koonce said. “I was all about playing because of the competition. I was trained to do that at a very early age, and I wanted to be with my friends. It’s a personal choice to play through the injury and play when you’re hurt. But I recommend that you just rest and come back when you’re healthy.”

“This movement toward a safer environment for athletes is going to be as much about George’s (Koonce) message as it is the science,” McCrea said. “This is where science and culture have the choice to merge or collide. In the past three years we’ve made great progress in convergence between the NFL and culture.”

McCrea said concussions have only been brought to the nation’s attention because of the high-profile nature of athletes in the NFL and National Hockey League.

McCrea said the stigma that a concussion only results from being rendered unconscious is fickle, and that if physicians are using that as the primary determinant of whether an athlete has a concussion, they are missing 90 percent of all concussions.

Smith, the director of Student Health Services, approached the presentation through the topic of allowing athletes to return to play. Specifically, she spoke of injured athletes at Marquette and how Student Health Services approaches concussions.

“Annually, all of our athletes undergo baseline evaluations,” Smith said. “We talk to them about their concussion history, we ask them about their risk factors and what medications they might be on. We do a baseline neurological exam. We do baseline cognitive evaluations. We are able to use a computerized program to talk about this. We do balance testing, and we apply all of this information post-concussion and compare it.”

Smith said athletes who sustain a concussion are not allowed to return to play the same day. She said symptomatic athletes are closely monitored before being allowed to play and that younger athletes often require conservative concussion-management.

“Concussions are an inevitable consequence of sport, and they cannot be prevented,” Smith said.

The importance of concussion-prevention and the scientific advances was presented at the beginning of the panel by William Cullinan, dean of the College of Health Sciences.

Cullinan said the human brain has some 86 billion neurons and is responsible for everything from personality to behavior. Therefore, all the recent concerns that have arisen concerning concussions are incredibly relevant today.

Cullinan said that up to 3.8 million concussions are reported every year. Players mostly get concussions from contact and collision sports, and there is increasing concern in the medical community about the severity of concussions.

Correction: The photo caption accompanying the print version of this story on Jan. 29 misidentified the man in the photo as George E. Koonce, Jr. The photo is in fact of Michael McCrea, a professor of neurosurgery and neurology and director of brain injury research at the Medical College of Wisconsin who also spoke at the event. The print story also misidentified Koonce as a senior athletics director at Marquette. Koonce is in fact a director of development for the university. The Tribune regrets the errors.