Marquette students have never been implicated in a cheating scandal as large as the one that’s currently rocking Harvard University, where school officials are investigating suspicious similarities in more than one hundred take-home final exams from a Spring 2012 government class. While such a case has not arisen here, professors on campus maintain that preventing academic dishonesty is a problem that is not unique to Ivy League schools.

“Faculty wish it were rare,” Pamela Nettleton, an assistant professor of journalism in the College of Communication, said. “But it seems it is not.”

Nettleton has taught large 250-person lecture courses and smaller courses in more specialized topics. Like most professors, she puts a detailed account of the university’s policies pertaining to academic dishonesty in her syllabus. Despite this warning, Nettleton says she comes across academic dishonesty of some type every semester.

Academic dishonesty is both a violation of the student code of conduct and the university’s policies and procedures on academic honesty, according to the text within Marquette’s 2012-13 student handbook. The student code of conduct says that participating in “any form of dishonesty, including cheating, plagiarism, fabrications or assisting others in doing so is an infraction subject to disclipinary action.”

According to the Division of Student Affairs Annual Report 2009-10, the number of students charged with dishonesty in conduct board hearings rose from nine incidents during the 2009 fall semester to 16 in the 2010 spring semester. Out of the 25 charges in the year, only 17 students, in total, were found responsible.

Since each college manages its own incidents of academic dishonesty, these reports may not accurately reflect the pervasiveness of the cheating culture on campus. According to Gary Meyer, the vice provost for undergraduate programs and teaching, the university does not have a compiled number of the reported cases that occur each year.

Christopher Perez, assistant dean for academic affairs in the College of Engineering, said there have been 60 reported cases in his college since fall 2008. Perez said he normally receives five notices each semester but has accumulated up to 15.

The College of Business Administration and the College of Nursing did not reveal their numbers of academic dishonesty incidents.

“While we could go back and count up instances (of academic dishonesty),” Margaret Callahan, dean of the College of Nursing, said, “we find it more helpful to focus on the positive approaches that foster a culture of honesty and integrity.”

The College of Communication, the College of Arts & Sciences and the College of Health Sciences also declined to comment.

Among Marquette’s most recent attempts to confront academic dishonesty was the creation of a subcommittee on academic integrity during the 2010-11 academic year by Provost John Pauly, Meyer said. The subcommittee submitted a final report in June 2011, according to Meyer, which was then reviewed in a University Academic Senate meeting February 20, 2012.

In the report, the subcommittee made several recommendations to the provost – most of which revolve around integrating the notion of academic integrity into Marquette’s community. Specifically, the subcommittee suggested making “integrity” more clear in the Marquette educational mission. This includes forming a comprehensive education program that encourages academic integrity, developing a centralized system for administering a comprehensive academic integrity policy and actually creating a code of academic integrity.

Meyer said Pauly is currently deciding how to proceed with these recommendations.

The university also retains a membership in the International Center of Academic Integrity. Last September, Marquette announced in a News Brief that it updated the software of its reporting hotline, EthicsPoint, to now allow students and faculty to anonymously report misconduct of any kind, including academic dishonesty and cheating.

According to its website, the ICAI is an organization of academic institutions based at Clemson University that aims to “combat” academic dishonesty and preserve academic integrity in higher education through the facilitation of conversation and provision of relevant resources.

“As a citizen, I am much more concerned with attitudes in broader society that condone the pervasive intellectual dishonesty that we confront every day and everywhere,” Dale Noel, a Marquette professor of biological sciences, said. “It infects us all.”

When attempting to answer why students decide to engage in these dishonest tactics, the responses varied among professors.

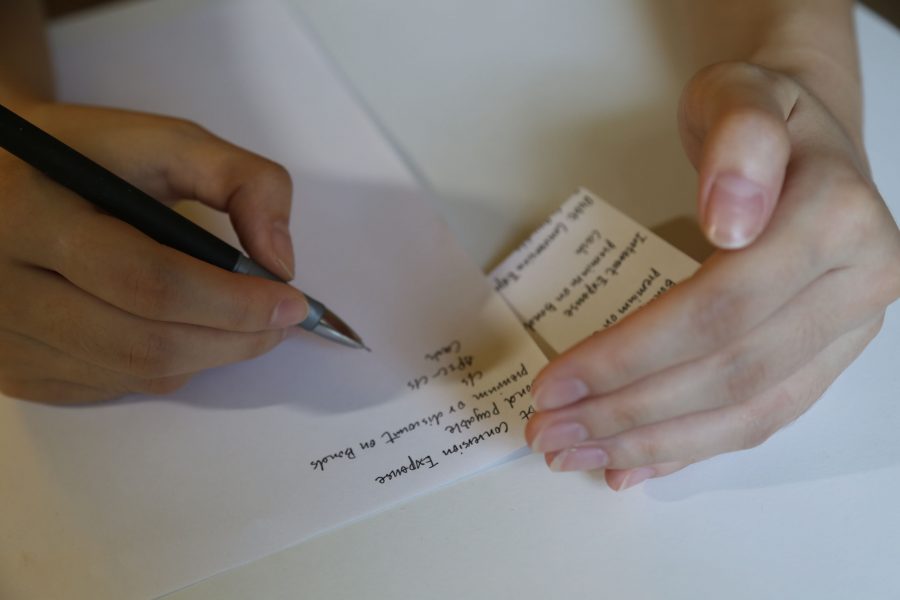

“I’ve seen a student approach assignments not as learning opportunities or ways to master material, but as if they were punishments,” Nettleton said. “Thinking like that, you might justify ways of working around doing your work. You might think of instructors as punishers, then think of yourself as a victim, and then tell yourself it’s morally acceptable to cheat.”