In the 20th century, the idea of “being green” was beyond any stretch of the imagination. One of America’s greatest architects and Wisconsin native Frank Lloyd Wright defied the limits of his generation by integrating nature into his residential and commercial designs.

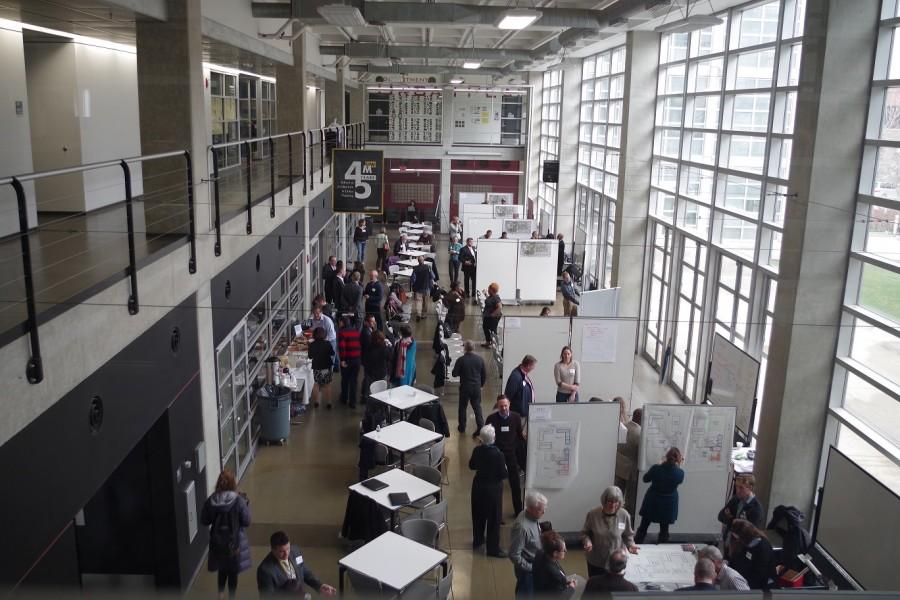

From Feb. 12 to May 15, the Milwaukee Art Museum presents “Frank Lloyd Wright: Organic Architecture for the 21st Century.” The exhibition celebrates the 100th anniversary of Taliesin, Wright’s home, studio and school in Spring Green, Wisc., as well as the 10th anniversary of the museum’s iconic, winged Quadracci Pavilion, designed by Wright-influenced architect Santiago Calatrava.

The exhibit is a major survey of Wright’s work, featuring more than 150 pieces, said chief curator Brady Roberts.

The works are primarily drawings on loan from the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives in Scottsdale, Ariz., but decorative arts, murals, digital animation and rare archival film footage are included as well. Thirty of the drawings in the exhibit have never been publicly displayed before.

Because Wright’s body of work encompasses hundreds of completed projects and still more unused designs, Roberts needed assistance to fully connect with his focus on nature. He found help in Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, vice president and director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, who served as guest curator of the exhibition.

Pfeiffer also offered a living connection to Wright himself, having worked with the architect for 10 years. Without that experience, Roberts said, navigating through Wright’s work would have been impossible.

Roberts and Pfeiffer decided to look at Wright’s architecture from a new perspective for the exhibition, through the lens of the 21st century. Shaping this perspective is Wright’s connection to nature, which magnifies itself in his work.

Roberts said Wright would describe “organic architecture” with three elements: time, people and place.

“By time, he meant technological innovation, which allowed him more freedom,” Roberts said. By exploiting the technological movement throughout his career, he added, Wright was able to design with a forward-thinking and futuristic approach.

As an architect, Wright was focused on the locale surrounding his works. He liked using local materials, and his designs were always a response to the surrounding terrain — he wanted them to reflect the landscape.

“He always said nature was his muse,” Roberts said.

Wright’s desire to design beautifully practical houses and integrated cities connected to nature is unfamiliar territory to the surveyors of today, noted Roberts, who offered up “cookie-cutter” houses and cities as the antithesis of Wright’s mission.

“Wright recognized early on that we were increasingly losing our connection with nature … particularly (in) big cities,” Roberts said. “He believed in a way to celebrate new technology and still connect to nature.”

Wright’s belief in “using what’s already there” is part of what makes him a timeless architect, said Mark Federle, a professor of civil and environmental engineering in Marquette’s College of Engineering. Instead of changing the landscape to fit the building, Wright fit his design into the landscape — an approach considered outlandish 100 years ago.

“He had a truly unique approach to design, and he stuck true to that design throughout his entire career,” Federle said. “He was green before green was cool.”

Lynne Shumow, curator of education at the Haggerty Museum of Art, said Wright received harsh criticism for his ideas, which were later deemed to be too innovative for his time. For that, she said, his work should be praised and should inspire architects today to take such chances.

“His ideas shed light on how we can integrate landscape with art today,” Shumow said.

“Frank Lloyd Wright: Organic Architecture for the 21st Century” begins Saturday and runs through May 15 at the Milwaukee Art Museum. For more information, visit mam.org or call 414-224-3200.