Many commentators characterize the recent health insurance reform law as a historic achievement on par with transformative legislation like the Social Security Act, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the creation of Medicare and Medicaid.

Critics lament that the reform is partisan and unconstitutional. These criticisms are unwarranted. More importantly, in its reliance on for-profit insurance companies and market-based designs, this law is premised on the assumptions of the conservative ascendancy that took hold during Reagan’s presidency.

The law may prove a lost opportunity to establish an effective progressive policy program. By enabling those under the age of 26 to remain on their parents’ insurance, preventing denial of coverage for pre-existing conditions, and extending coverage to 31 million previously uninsured taxpayers, the reform establishes a new tenet of American democracy: Everyone is entitled to health care. That idea will be difficult to undermine.

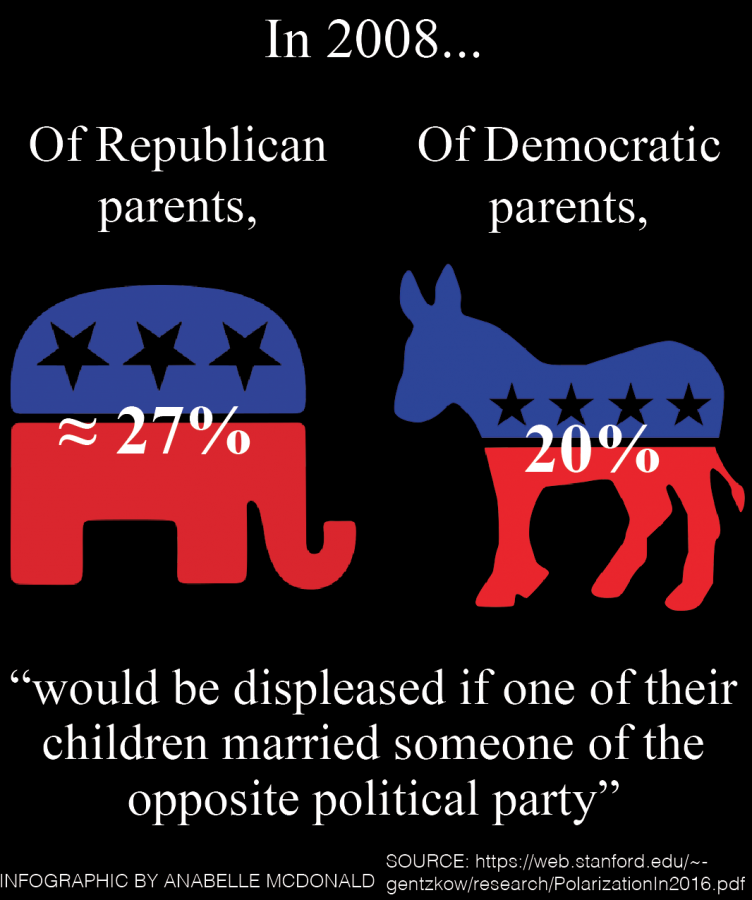

Yet, unlike social security, Medicare and Medicaid, which all garnered congressional Republican support, the new reform had none. However, criticism of partisan extremism does not consider how the national political parties have re-calibrated since 1980, becoming ever more ideologically unified and polarized.

That Republicans did not vote for the reform may say less about the law and more about how our parties have changed over time. Since the allegedly partisan bill is now law, criticism has shifted to its constitutionality.

Fourteen states’ attorneys general argue that Congress has no authority to compel people to purchase insurance. Their argument misunderstands the purpose of government, ignores precedent and does not acknowledge constitutional development.

Government regulation curbs instances where individuals acting in their own short-term rational self-interest create collective disaster. As a healthy young man, I could rationally forego purchasing health insurance.

The probability that I will need care is low, and insurance is an expense that might be better applied to other ends. But, if only the sickly purchase insurance, then the pool of money needed to cover their needs would not be large enough, and the system would collapse. The mandate solves this problem and the Supreme Court has ruled similar congressional regulation constitutional under the commerce clause.

The government, under the Agricultural Adjustment Act, fined a farmer for growing more wheat than allowed even though he did not bring it to market; he fed it to his livestock. In Wickard v. Filburn (1942), the Court considered the act constitutional. The farmer’s behavior undermined the act’s attempt to maintain a price floor for wheat by regulating supply.

The farmer’s “homegrown wheat … competes with wheat in commerce” because it lowered his own demand. Such behavior, writ large, would drive down price and undercut the regulation. In Wickard, the Court recognized the same problem that the mandate solves and considered the corrective measure constitutional.

Recent cases have narrowed Wickard’s reach, but they have not undone its underlying logic. Despite the mandate’s constitutionality, Virginia has balked at the law, thereby breathing life into the long-dead notion of nullification.

Nullification, popularized in the 1830s, discredited by the Civil War and revived to justify opposition to Brown v. Board of Education (1954), holds that state officials do not have to implement federal laws that they contend violate the Constitution.

Nullification runs counter to the Constitution’s supremacy clause and delegitimizes federal authority. Its advocates fail to recognize that the Constitution differs from the Articles of Confederation, which it replaced.

The Constitution grants more power to the national government, and its 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments continue that trend. Nullification foments dangerous politics, which do not recognize the loyalty of opposition. As such, a political culture premised on reasoned persuasion breaks down and violence may ensue. Sporadic instances of violence are already evident.

A progressive democrat may take pride in the achievement of universal entitlement to health care. But, if you were hoping that Obama would set the terms of politics on new progressive footing, the reform offers little reconstructive potential. That lack of transformation makes the opposition’s rhetoric curious and alarming, for it is out of sync with what the reform achieves and how it achieves it.

More people will gain access to health insurance and that insurance will be more reliable, but the policy is market-based and establishes little new regulatory infrastructure. In short, the expansion of coverage hardly changes the underlying conservative terms of politics in play for the past 30 years. We would do well to consider whether the opposition’s roots have little to do with the passage of a health reform per se and stem from some other concern.

Melkin • Apr 14, 2010 at 11:09 am

“But, if only the sickly purchase insurance, then the pool of money needed to cover their needs would not be large enough, and the system would collapse.”

Exactly. ObamaCare imposes tiny penalties on those who do not purchase insurance. People will quickly figure out that they are better off paying the penalty and only getting insurance when they need it, leading to a collapse of the system. This is already happening in MA.