When Nadja Simmonds finally sat down to receive her birth control implant last spring, her mother briefly hesitated, saying they could wait until the summer.

The provider’s response was one that stuck with Simmonds, now a sophomore in the College of Communication.

“The lady said, ‘If she doesn’t want to be pregnant, she has the right to not be pregnant,’” Simmonds said. “And that really stuck with me because I’m like, ‘Yeah, that’s right. If I don’t want to be pregnant, and I want to be sexually active and I want to be safe, I have a right to that. Especially when there’s information and safe tools and resources out there for me to use. I have that right.’”

For Simmonds, the issue of sexual health and protection hits close to home. Two of her closest friends have been sexually assaulted. Now, she said her birth control implant is primarily a method of protection. On campus, she finds herself interacting with people who have differing views on sexual health.

“I feel like here, I know a lot of people who either can’t talk to their parents about contraceptives or they say, ‘I don’t want to talk about it. We’ll worry about that when it comes to it.’ I’m like, ‘Worry about what? Getting pregnant? Because once that happens, you’re pregnant. You’re on a whole different level of responsibility there.’”

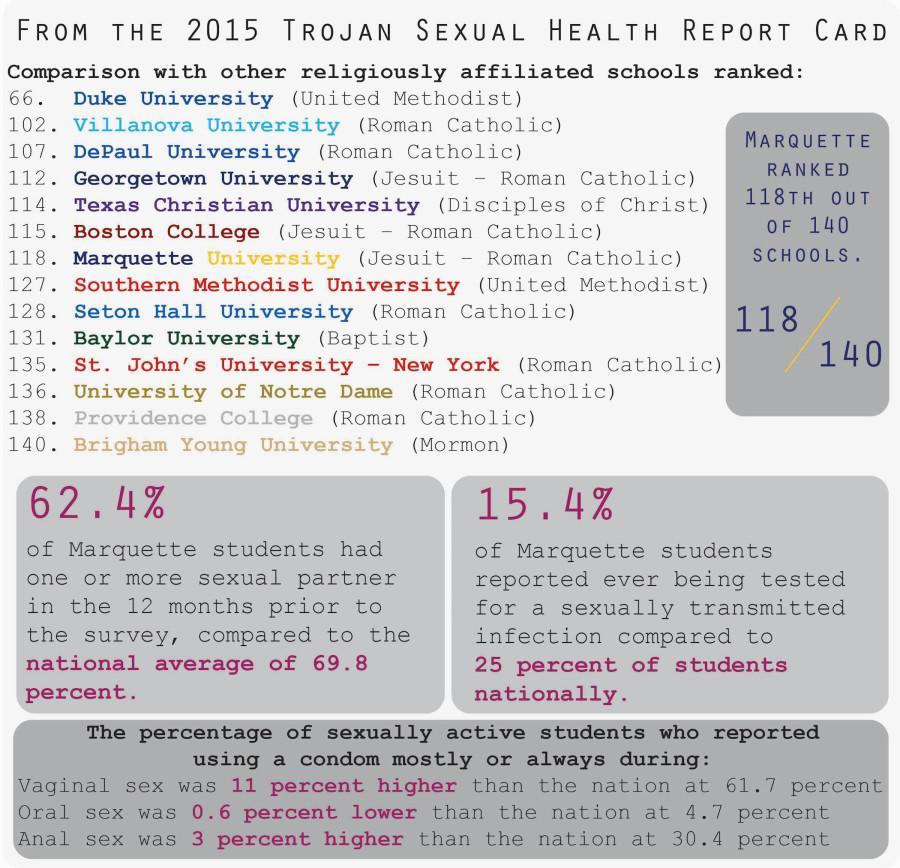

Contraceptive availability is one criterion evaluated by the 2015 Sexual Health Report Card, an annual sexual health resource study sponsored by Trojan Brand Condoms. Of 140 universities ranked nationwide, Marquette was 118th.

“It’s kind of embarrassing really,” said Heather Saucedo, a former case manager at the now closed Marquette Neighborhood Health Center. She said Marquette could have been the difference.

Over the years, Marquette’s rankings have been relatively consistent, staying near the 115 to 120 mark. However, Robin Brown, associate director of health and wellness at the Marquette Medical Clinic, cited several concerns with the ranking, pointing out that it represents only 140 schools and that Trojan sponsored the survey.

“It’s a corporation sponsoring this survey and ranking, promoting the sale and use of its product,” she said. “So you have a built-in bias with a survey such as that.”

Bert Sperling, lead researcher of the report card, said that the 140 schools were selected based on their national reputation and influence. He said there are about 2,500 schools with four year programs, but the 140 chosen include over 30 percent of the nation’s undergraduate population.

To overcome the bias of Trojan sponsorship, Sperling explained that the company let his firm, Sperling’s Best Places, do the research with little interaction.

“Because it is funded by Trojan, I think it’s only natural to follow the money,” he said. “What’s the point? Is this just an advertising mechanism? In actuality, we don’t have any contact with Trojan.”

Sperling said Trojan contacted his firm, but his firm proposed the methodology and focus for the study. He said for the 10 years this study has been conducted, Sperling has remained independent from Trojan’s direction.

Brown said Marquette decided to participate because the institution is interested in sexual health, and access to the data could be beneficial. However, Brown urged caution when deciphering Marquette’s ranking. Among religiously-affiliated schools, Marquette ranked seventh out of 14 religious universities. Only one religiously-affiliated school was in the top half of the 140 schools ranked.

“When you’re looking at something like this, the Catholic, faith-based Jesuit schools should probably be pulled out, because otherwise you’re comparing apples to oranges,” she said.

Of the 11 categories of sexual health resources the report card reviewed, two are not offered at Marquette due to its Catholic values: contraceptives and condoms. The remaining categories included quality of sexual health information available, sexually transmitted infection and HIV testing, sexual assault programs, education and outreach, website usability and quality and clinic accessibility.

Sperling said he did not differentiate religious affiliations on purpose.

“I think it is fair to go ahead and compare the (religiously affiliated) schools with all the others because we are comparing them without any sort of bias or singling them out as religious schools or not religious schools,” he said. “We’re just looking at the information that’s provided to students.”

He said schools might choose not to provide sexual health resources or information for a variety of reasons, including the objection to be seen as condoning premarital sex.

“That’s something they don’t feel comfortable with, and we certainly respect that, but there are certain consequences that go with it,” Sperling said. “It means students don’t get the information.”

A right or a choice?

Until last summer, the Marquette Neighborhood Health Center offered birth control and contraceptives to students, faculty and staff.

Operated by the College of Nursing, the clinic began to focus on women’s healthcare in 2011 and moved off campus in 2013. Heather Saucedo, formerly a case worker at MNHC, said students had taken advantage of the center’s services since it began as a primary care practice on campus in 2007.

Like the medical clinic, the center offered STI testing, men and women’s healthcare and other basic services. Unlike the medical clinic though, the university allowed the center to offer birth control to those who asked for it – though they could not advertise this service.

“It was a constant struggle, and we talked about it in every meeting,” Saucedo said. They were told that the subject was controversial and the goal was to respect Marquette’s Catholic roots. They could give birth control out, but few people knew.

“It definitely hurt the student population,” Saucedo said. “If more people knew, it could have helped a lot of students. (Marquette was) pretending college students don’t have these needs.”

Alex Dinkel, a sophomore in the College of Arts & Sciences, said that while he does not believe Marquette should have to provide contraceptives to students, there should be better communication overall about the sexual health resources available.

“There’s no information on it,” he said. “There’s no conversation on sexual health. I didn’t even know you could go to the medical clinic and get tested.”

Saucedo said that the inability to publicize the health center’s birth control resulted in many people not knowing the resource was at their disposal. After the clinic moved and eventually shut down, she said it is likely students began going to the Planned Parenthood on Wisconsin Avenue, as it is the next closest resource for such services.

The Planned Parenthood on Wisconsin Avenue offers contraceptives to students and community members.

Compared to the openness of discussion Saucedo said she experienced as a student at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Marquette’s lack of such resources and the inability to publicize the former clinic’s resources was frustrating.

Brown said the medical clinic acknowledges the protections condoms provide and refer students to several Milwaukee clinics for contraceptives or procedures they may not be able to perform, but when it comes to “the two Cs” (condoms and contraceptives), the clinic was not going to budge.

She said through referrals and students’ own resources, people are getting what they need.

“The student population is very supported by their parents, and they’re very, very intelligent about finding their own resources, as well as finding us,” Brown said. “We’re one of the resources, but there are many others, and students talk to each other, they go on the web, they talk to their … families, so I would say that it’s very, very rare that someone is not able to receive the service or the care they need.”

Saucedo said it is a poor assumption that familial support or financial stability exist, or that students have those connections. She said many college-age students are unaware of resources like the Family Planning Waiver Program under Wisconsin Medicaid or area clinics, but an even greater hindrance is that students lack time and will not likely seek out healthcare.

“If we’re really trying to do better for the patient, (we would) offer comprehensive services,” Saucedo said. “Where else could (a practice) justify doing this?”

Looking forward

It’s 10 a.m., and a Marquette Hall lecture is filled nearly to capacity with students aiming to become researchers, healthcare professionals or work in a science field.

The class: microbiology. The topic of the day: sexually transmitted infections.

The professor, Laurieann Klockow, explains the rampant nature of diseases that often go unnoticed by people who are infected. Nearly half of the people infected with STI’s across the nation annually are 15-24 years old.

“So, the age of most of you in this room,” Klockow told the class.

She listed three ways to prevent STIs: abstaining from sex, having a monogamous relationship with a non-infected person and using latex condoms. Some students whispered to their neighbors and chuckled, others shifted in their seats. Outside of the scientific safety of the classroom, dialogue about sex is not very common.

“I see a lot of groups starting up for (diversity issues),” Simmonds said. “But I don’t see (many) that are like ‘Hey, let’s talk about safe sex.’”

Simmonds said that the resources the counseling center offers are very helpful and she has taken advantage of them. She also noted the creation of a post-abortion counseling group on campus. Still, she said that while she has a very open friend group that talks about sex, she doesn’t see her experience as representative of the campus climate and does not feel comfortable visiting the university’s medical clinic for such purposes.

For Dinkel, who is a practicing Catholic and centers his idea of sexual health on Pope John Paul II’s Theology of the Body, the concept of a human life and natural conception are core values that he believes Marquette can and should justify sticking to. However, he agreed that the university’s low ranking is deserved, mainly because of the lack of conversation.

“There’s a lot of misconceptions that comes with Catholic values and sexual health,” Dinkel said. “The fact that it took Pope John Paul II to really open up the curtains and dust off (the idea) and start talking about sex – I think that was really important, and it’s still kind of under-discussed, because a lot of people think that the Catholic Church is anti-sex. That’s not the truth at all.”

He said that Marquette could be doing more.

“I think that the most important thing that we can do is just start a conversation,” he said. “Marquette doesn’t really do anything. They could at least set forth some sort of an initiative and empower student groups to spark a conversation about sexual health.”

Brown said this year the medical clinic has more services, up-to-date testing methods and a larger staff, and they cut the price of STI testing in half (the cost is the minimum to have the sample sent to a lab). The clinic also launched a sexual health peer education program in freshman residence halls. Currently located in Cobeen Hall, the six-week health and wellness program includes sexual health.

Brown said she would like to have more offerings of that program available in the future. Last year, Brown rewrote the clinic’s website to provide more straightforward information about testing, safe sex and online resources. She also referenced the university-wide efforts to improve the community’s response to sexual assaults. Twenty-seven students took advantage of free HIV testing days Dec. 1 and 2.

Sperling said such improvements are not to be discredited. While some schools may not necessarily move up in the rankings, there has been an overall improvement in sexual health resources available at universities nationwide. He said he has no doubt that every student health center cares for its students. The goal of the report card is to address possible barriers between students getting the healthcare they want and need, he said.

All admitted that there is still work to do.

“We do as much advertising as we’re allowed in the venues that we can use,” Brown said, referencing posters in residence halls and clinics, news briefs, social media and the clinic’s website. She said an important area of improvement is in communication.

“I’d like to see more,” she said. “I’d like to see more.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misattributed the following quote to Heather Saucedo, instead of Robin Brown. The Wire regrets the error: “The student population is very supported by their parents, and they’re very, very intelligent about finding their own resources, as well as finding us,” Brown said. “We’re one of the resources, but there are many others, and students talk to each other, they go on the web, they talk to their … families, so I would say that it’s very, very rare that someone is not able to receive the service or the care they need.”