A missing picture

Marquette’s reporting to the federal government misses

just less than half of sexual assaults on campus

April 23, 2015 | Written by Rob Gebelhoff, McKenna Oxenden and

Patrick Thomas; photos by Rebecca Rebholz; design by Theo Syslack

-

- Paul Mascari, chief of the Department of Public Safety, said counts reported by the university in its morning reports and to the federal government are difficult to reconcile due to the boundaries included.

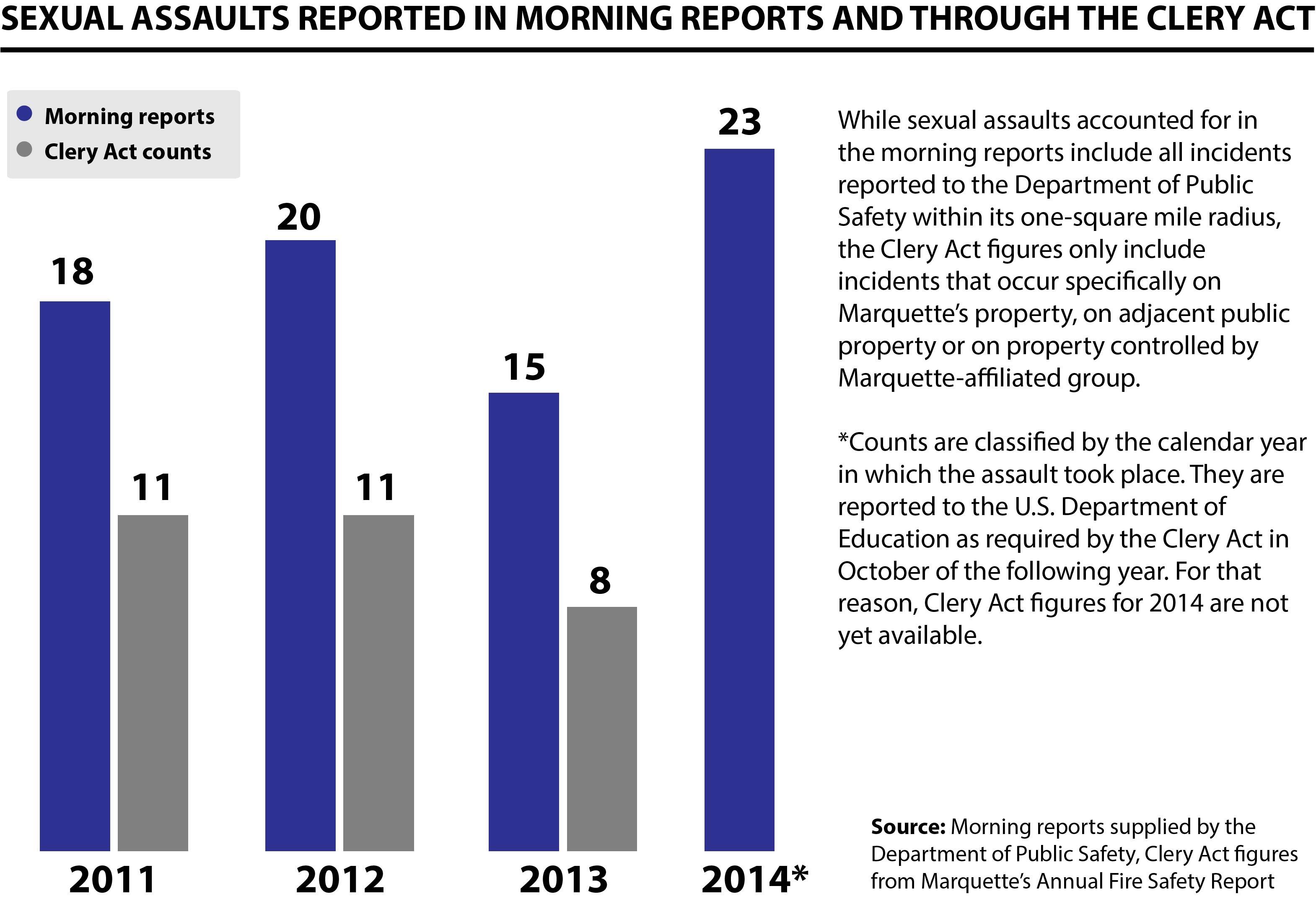

Over a three-year period starting in 2011, Marquette reported a total of 30 sexual assaults to the federal government, but that only accounts for just over half of the sexual assaults that took place in its one square-mile patrol zone.

The Department of Public Safety reported 53 sexual assaults in its daily morning reports during the same time period represented in its reports to the U.S. Department of Education, an analysis of DPS’s documents shows.

But the discrepancy isn’t a mistake, and in fact, it’s common among reports from colleges across the country.

“It’s kind of tough looking at those two (sexual assault counts) and reconciling them,” DPS Chief Paul Mascari said.

Mascari attributed the difference in reports to the specific boundaries in which universities are required to report crime to the Department of Education by the Clery Act of 1990.

Clery statistics include crimes that occur on property owned by the university; the property adjacent to university-owned property such as the sidewalks and streets; and non-campus property leased by the university or owned or leased by an approved student organization such as fraternity and sorority houses.

Those boundaries exclude any non-university house or apartment building where students live, where a good chunk of sexual assault incidents occur.

Take, for example, a sexual assault that was reported by a student on August 24, 2014 in the 800 block of N. 14th Street. Even though DPS put the incident in its crime log three days after it occurred, it won’t be counted in the university’s 2014 count submitted to the federal government, Mascari said.

That doesn’t mean that Marquette can choose when to publicly report sexual assaults. Marquette must report all sexual assaults that take place in its “patrol jurisdiction” — a loosely defined term.

While many universities limit their patrol jurisdiction to their physical Clery geography, Mascari said Marquette has expanded the patrol jurisdiction to its one-mile radius.

“We’ve expanded it, and we can contract it as well,” Mascari said. “But we want to serve our students, not only where they go to school, but also where they’re living in the off-campus area. We’ve expanded it to that one-square mile, so we have to report everything that happens there.”

‘DOING SOMETHING RIGHT’

The extended boundaries mean DPS has to publicly log all incidents in its patrol zone beyond university-owned property, even if the victims in the reports are in no way affiliated with the university.

That is rare, though. In all reports of sexual assaults made available by DPS, covering cases going back to October 2010, only one case in 2013 included a victim specifically reported as not affiliated with the university. Two were identified by DPS as alumni and the rest were students.

Regardless, Marquette’s relatively higher amount of sexual assault incidents means it goes beyond what is required by federal law to report, which is why some national sexual assault transparency advocates are, perhaps ironically, encouraged by Marquette’s relatively higher sexual assault counts.

“It means (Marquette is) doing something right,” said Annie Clark, co-founder of End Rape On Campus, a national advocacy group that advocates for sexual assault victims and has been pushing for greater transparency. “I wish all schools would do that.”

View Sexual assaults at Marquette in a full screen map

This underscores another problem, though: Reporting procedures required by the Clery Act don’t show the whole story about sexual assaults on college campuses.

The Department of Education reported more than 5,000 sex offenses in 2013, but the U.S. Department of Justice said the actual number of offenses may be at least six times that number.

A group of members in Congress, led by Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-M0.), introduced legislation last year that would force schools to go further in reporting sexual assaults, including publishing annual surveys of students’ experiences with sexual violence. The proposal also includes hiking up penalties for Clery Act violations, up from the current penalty of $35,000 to $150,000.

Although the bill received bipartisan support, it attracted opposition from a number of groups. Some argued it doesn’t go far enough in increasing police presence and promoting thorough investigations. Others have said it contributes to a system that unfairly treats those accused of sexual misconduct.

While changes to the rules in the Clery Act remain under debate, Clark said the law includes other requirements that would not be subject to reform, like mandated emergency notification systems when crime happens on campus or the sexual assault victim’s bill of rights.

“The Clery Act is more than just a crime log,” Clark said. “The point is to make people aware of what’s happening.”

For Susannah Bartlow, director of Marquette’s Gender and Sexuality Resource Center, increased transparency on campuses through greater reporting translates to reducing the stigma that is often attached to sexual assault victims.

“We want to have constant conversation on this,” Bartlow said. “It helps us to understand it’s a community culture change. I would love to see us get to a place in terms of national policy for transparency.”

This is the first article in a three-part series looking into the reporting of sexual assaults at Marquette. Click here to see the rest of the series.