Before she was the “New York Times'” first–ever woman to be appointed editorial page editor or held a seat on the Pulitzer Prize Board, Gail Collins was an inquisitive and bright-eyed student at Marquette University.

Collins grew up in a fairly conservative town and attended a Catholic girl’s high school in the Cincinnati area before making the move to Milwaukee and enrolling at a Jesuit institution for her college years. Between Collins’ upbringing and the general ignorance of the time, she was not often exposed to LGBTQ+ related issues.

“When I went to Marquette, I was pretty reasonably conservative,” Collins said. “I hadn’t had much outside experience, and I was certainly not rebellious in any way, shape or form.”

However, she found herself thrust right in the middle of a gay rights protest on her college campus. It all happened when Allen Ginsberg came to town.

The power of poetry, a double-edged sword

Collins was sent to a student conference with a few other peers the summer before her senior year of college that took place at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. There, she met poet Allen Ginsberg.

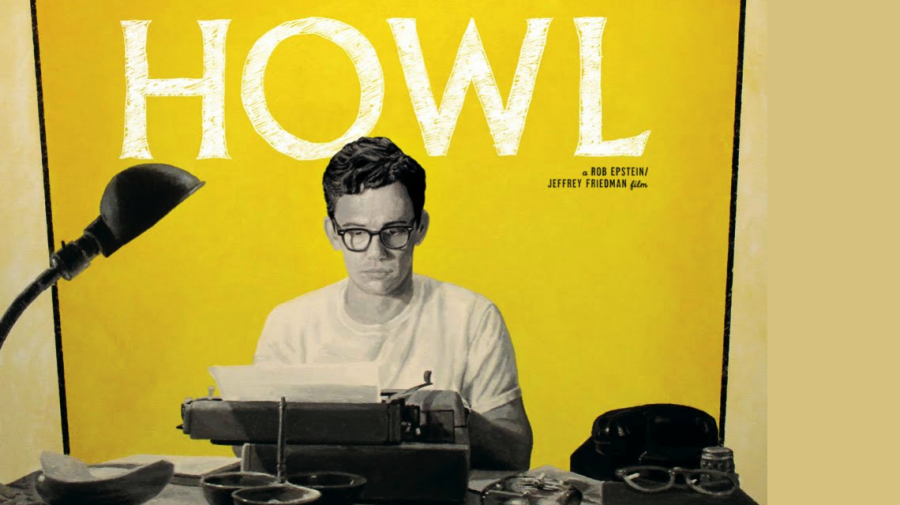

Ginsberg was an American poet and writer influenced by Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs and Neal Cassady — other formers of the Beat Generation. He was a highly decorated poet who won awards such as the National Book Award for Poetry and the Robert Frost Medal. However, he is most synonymous with his poem “Howl.”

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked / dragging themselves through / angel-headed hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night …”

Lines such as this proved to be dynamic, provocative and a bit unsettling depending on the reader’s perspective.

As a part of the Beat Generation, Ginsberg participated in peddling out this kind of daring poetry to the public.

“Just that idea (the beat movement) of a new way of looking at poetry and literature, that was sort of part of the rebellious spirit of the era even when it came to things like rhythm and words,” Collins said.

But to many college students, Ginsberg was simply “… famous at the time for being sort of a hippie poet,” Collins said.

Once on campus at Illinois, Collins had the chance to meet and speak with Ginsberg. She admitted that she was “near illiterate” when it came to poetry, but she felt welcomed by Ginsberg and remembered his kindness vividly.

“He was the nicest guy in the entire universe,” Collins said.

During their interaction, Collins and her peers asked Ginsberg if he would be willing to read some of his poetry at Marquette if he ever were to be in or around the Milwaukee area. He told them that he would love to.

The plans were being coordinated and finalized for Ginsberg to do a reading on campus, but the event was stopped in its tracks.

“Then, the (Marquette) administration looked him up and found out that he was taking his clothes off at a reading and that he was a lefty and that he was very into sexual liberation — things that Marquette was not into then — so they said he couldn’t come,” Collins said.

At the time, Father Richard Sherburne was the dean of students.

Taking action with the help of a friend

Soon after hearing this news, Collins and her peers formed a group that stood up against this decision and fought for their right to free speech. In 2022, Collins wrote an opinion piece about this for the “New York Times” titled “When Allen Ginsberg Came to Town,” where her longtime friend, writer Con Lehane, commented on his experience as part of the student rebellion:

“As I remember things, homosexuality was the reason the administration gave for canceling Ginsberg’s appearance,” Lehane stated, according to Collins’ piece.

Collins interjected to say that Lehane is still one of her closest friends and that he lives in Washington, D.C. now, but she still sees him once or twice a year along with his children and grandchildren.

Lehane was — as Collins noted — far more involved in the political left than her. But still, this was something new for both of them and she knew it was important to take action.

“It was just inconceivable to me that he could be a ‘bad guy’ — and of course, our knowledge of homosexuality back there was really, really pathetically limited,” Collins said.

Collins said that a group of students knew they “wanted to do something” about this incident and that the administration had given them a perfect way in to form a rebellion of sorts.

“It was like this opposition movement,” Collins said of their efforts to give administration a ‘piece of their mind.’

And that they did.

“We got very rebellious — we had demonstrations and a sit-in at the dean of students office,” Collins said. “Ginsberg came and we marched through the city. He went to UWM and gave his speech there.”

A forceful comeback, an undeniable turning point

Although he could not speak at Marquette, Ginsberg was down the road at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee where he read some of his poetry to its student body.

Collins and her friends went to the event. She said that they were interested to see what he had to say and how he would be received by the students there.

“‘We will all go upon the same cross ultimately — there is no need for anger,’ I remember Ginsberg telling the crowd. Still didn’t have much of a grasp of poetry, but I knew a good comeback when I heard one,” Collins wrote in her opinion piece.

Beyond just an opening for her to experience young adult rebellion and pushback, Collins said that she remembers this to be a major turning point in her life.

“I always saw myself as a moderate-works-within-the-system person before. Thinking back, I wonder how much longer it would have taken me to figure out I was against the war in Vietnam if I hadn’t been a veteran of the Ginsberg censorship fight,” Collins wrote.

Collins also said that, although she had already known she wanted to be a journalist, this experience opened her eyes to new possibilities within that career.

“I came to realize, again, how unlimited being a journalist was,” Collins said.

It also opened her eyes to the importance of standing up for social change and progress. A concern ahead of her time considering Collins’ young age and the decade she was living in.

Standing up for gay rights is something that Collins now regards as the “next wave of moving into the future” presently — comparing it to the progression women have seen in their legal and societal rights.

“The idea that women should be regarded as leaders and people who were capable of doing every single thing that guys did is something that only began in my era,” Collins said of modernizing the status quo, “and, to be honest, we didn’t know a thing about homosexuality back there.”

People can change and grow

There was much to learn and a long way to go. In that spirit, an olive branch was handed to Collins somewhat unexpectedly.

“Some time back – maybe about ten years ago – Marquette invited me back to give a talk and say ‘hi.’ So, I came back and the only pictures they really had of me were the ones where I was sitting in the dean of students office,” Collins said.

“After it was over, this sort of elderly guy came up to me and said ‘You don’t remember me but I’m Father Sherburne. I was the dean of students when you were there and that was my office you were sitting in. I’ve been retired for ten or fifteen years now in a monastery, but I left the monastery to come to see you today to tell you that you were right, and I was wrong.’”

Collins even remembered calling all of her friends from back then to inform them of what Father Sherburne said to her. Although, she did not hold any ill feelings towards the dean or Marquette.

“I had a great time — I think back on it very fondly. It’s (Marquette) a much better place in many ways now. You guys are getting a much more high level, exciting education than we got. But we got a chance to rebel against everything,” Collins said warmly.

A love long-held

Collins later bridged the gap between an interest in political issues and a love for writing by chasing a career in journalism. After graduating from Marquette, she went on to obtain her master’s in government from the University of Massachusetts–Amherst. Of course, later and after much grunt work reporting at other, smaller outlets, Collins landed herself a spot at the Times.

When first offered this position, Collins says that she told the inquirer that he was “out of his mind” to want her to be the editorial page editor. However, she took to the challenge when he told her that, “there aren’t that many first women left to do things anymore.” Unless she was interested in becoming the commissioner of baseball. She was not.

But, this opportunity for her was a long time coming.

She recalled that an early love for writing came largely from her mother — a wife and mom during the World War II era who was not granted the same kind of opportunities to pursue her dreams.

“My mother was really into it (writing),” Collins said, “but she never really got any opportunity to have a job or have a career, and she was always very into writing. When I kind of started playing around with it when I was a kid, she really encouraged me.”

Collins even noted that her mother registered her for an acting, writing and public speaking class within a small, private academy.

“I had to write something that I could perform, and so I did this sort of funny thing about a babysitter calling, talking to the mom of the kids and terrifying her with the report,” Collins said.

From then, she wrote about eight more of these short stories that went on to be published for children to perform as public readings. Collins was also involved with writing and journalism at an early age through other facets.

“I was in the school newspaper when I was like twelve, I think – so, I mean, I kind of always thought I would be a writer,” Collins said.

That was a large part of her choice to attend Marquette since they had a journalism program.

When Collins was a student at Marquette, she was offered the position of Journal editor. However, the tradition of student media was to have one male and one female co-editor. Collins was asked to make a selection between two male peers for who would be editor alongside her.

“Neither one — I just want it for myself,” Collins said.

Collins has carried that tenacious spirit and strong voice with her throughout her career. She now continues to write about American politics and culture for the “New York Times” balancing an informed arsenal and an edgy sense of humor.

This story was written by Grace Cady. She can be reached at grace.cady@marquette.edu.