Literacy is a big deal.

It has lifelong effects. People with lower literacy earn half of what their counterparts make, are more likely to report poor health and are less likely to pursue higher education which affects career opportunities.

This is a phenomenon that Maya Smart has likened to “reading for your livelihood.”

Smart has multiple roles in Milwaukee — “too many to fit on a business card,” she laughs. Some of which are educator as an affiliated faculty in the College of Education, parent, literacy advocate, wife of Marquette men’s basketball head coach Shaka Smart and soon-to-be published author.

Her debut book releasing Aug. 2, titled “Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six,” offers steps for caregivers to nurture language and literacy development as soon as a child’s wail enters the world. Smart’s book details the life of literacy like other developmental milestones: a skill needing practice and precision to be learned.

“You forget that children even have to learn what a letter is,” Smart says. “How do you know the difference between a ‘L,’ ‘one’ or a line?”

For all children, there was a time when parents needed to read aloud messages scrawled on birthday cards or convey menu options at a restaurant.

“You don’t think of it as a skill and something to be gained,” Smart explains.

Literacy is a skill not completely achieved for U.S. adults on a county, state or national level.

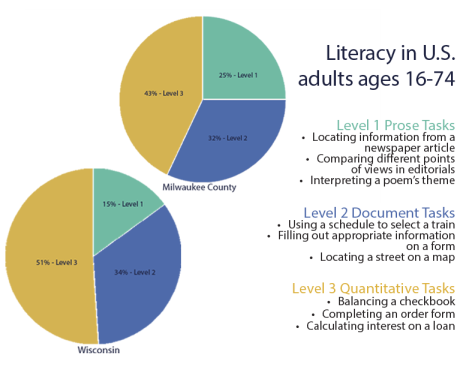

Data from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies estimates that Milwaukee County’s literacy rates for ages 16 to 74 are below Wisconsin and national average scale scores.

One in every four Milwaukee county adults are at or below the lowest level of literacy. This is the knowledge and skills needed to perform tasks like reading a news story from the Marquette Wire or scouring that brochure for that study abroad program you really want to do.

Milwaukee county adults at or below the second level of literacy is on par with the national and state averages at 32%. This means they can read the tiny black and white label on a bag of chips from Sendik’s or decipher the colorful Milwaukee county bus schedules that sit in the hallway of the 16th Street parking structure on campus.

Only 43% of Milwaukee county residents are at or below the third level of literacy. This is figuring out a tip after ordering lunch at Sobelman’s.

COVID-19 has negatively impacted literacy even more. A study from Stanford University shows that second and third-grade students were most affected, and their reading fluency is now roughly 30% behind typical expectations.

Marquette University’s Hartman Literacy and Learning Center is a campus resource that prepares teachers to effectively instruct reading while also providing children who struggle reading with additional instruction that targets their specific needs.

This specificity enticed Kathleen Clark, associate professor and director of the Center.

“Working in and directing the Hartman Center have been highlights of my professional life,” Clark says via email.

Clark has seen the research; she knows the lifelong impact literacy can have.

“That’s why it’s so important that teachers are prepared to teach reading well,” Clark writes via email. “We need to make sure that children get off to a successful reading start.”

Since she started at Marquette in 2004, Clark instructed an education course where students learned how to teach reading. Dominique Vazquez, who graduated from the College of Education in May 2022, was one of those 16 students in Clark’s spring semester class. The first half of the semester was instructional, but for the second half, every Monday and Wednesday afternoon, Vazquez joined a Milwaukee third-grader as part of his after-school reading program.

“For kids, (reading) can become a chore,” Vazquez mentions, “but it was our job to make it seem like it wasn’t anymore.”

Vazquez flipped through flashcards to help her student learn phonemic awareness. They also read together.

“I found out that he had an interest in national parks, so I would focus on books like that during the reading portion of our lesson plan,” Vazquez says.

After a book on national parks, they would turn to fiction; Vazquez says his favorite series to reread was “The Magic Treehouse.”

Vazquez’s student program is called Road to Reading, a road paved long before Vazquez ever appeared in the next lane.

“From the moment you have this child, you’re affecting their literacy trajectory,” Smart says.

But even if you’re not a parent or an education major, you still will affect the literacy of children in your life.

“(It’s important for) kids to have siblings, cousins, parents, teachers, all kinds of people in their lives that talk to them and listen to them and are really responsive,” Smart says. “Just even playing with them has a huge, huge impact, and it’s something none of us remember.”

This story was written by Randi Haseman. She can be reached at randi.haseman@marquette.edu.