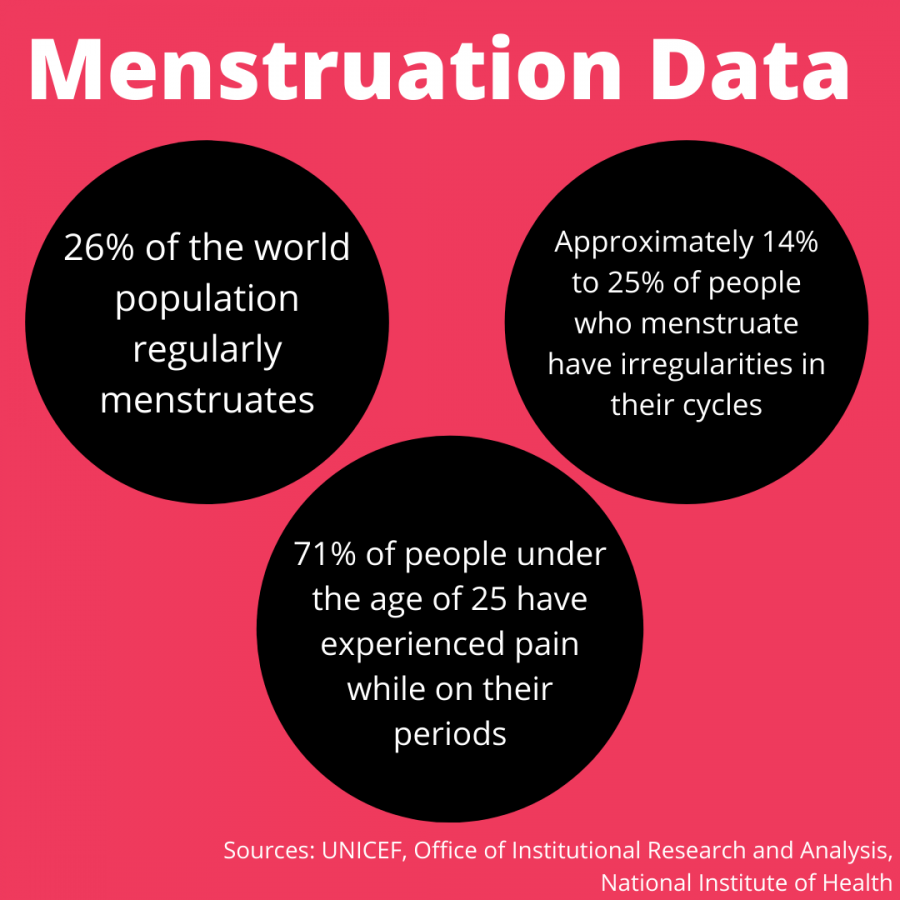

Menstruation is a regular occurrence for 26% of the world’s population, which are female-bodied people of reproductive age. At Marquette, that percentage is at about 54.8% for undergraduate students. An estimated 14-25% of people who menstruate have irregularities in their cycles, and another 71% of people under 25 have experienced pain while on their periods.

These can be anything from bad stomach cramps to chronic illnesses. All irregularities can leave people with severe pain and fatigue, making it nearly impossible to continue on with their everyday life. These conditions must be taken seriously and accommodated to in a college environment.

Many menstrual irregularities can be alleviated with hormone treatments such as birth control, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information. However, some conditions, such as endometriosis, when the uterine lining that is shed during menstruation grows on the outside of the uterus and can lead to pelvic pain and heavy bleeding, as well as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which results in cysts forming around ovarian follicles and can make it difficult for egg cells to reach the uterus and can lead to irregular and painful periods, will not always go away with hormonal treatment. Hormone treatment itself can cause unpleasant side effects like indigestion, mood swings and feeling sick, according to the National Health Service.

For PCOS specifically, people in a NCBI article describe going to multiple doctors before getting a diagnosis, and that the process of doing so is “exhausting” and “devastating.” An estimated 6-12% of people who menstruate have PCOS. Even if only 6% of women at Marquette had PCOS, that would still be 115 students.

More severe or chronic conditions like diabetes, thyroid problems or mental health disorders can have a major impact on the menstrual cycle, as well.

The Office of Disability Services exists on Marquette’s campus to help students who need accommodations in the classroom such as extensions on schoolwork or excused absences. In an email, ODS said that they identify a disability as “a physical or mental health condition that substantially limits one or more major life activity.” For menstrual health issues, getting accommodations are on a case-by-case basis. Fortunately, this means there’s a much more individualized approach to accommodations. As long as one has a proper diagnosis, recieving accommodations should be no issue.

However, getting a diagnosis for menstrual health conditions in the first place can be difficult and expensive.

Many menstrual health problems are brushed off as overreactions due to medical misogyny as well. Both male and female doctors’ internal misogyny can affect the way they treat female-bodied people.

The ODS requires a diagnosis by a medical professional before allowing for accommodations. This should not have to change due to our misogynistic medical field. However, the ODS should encourage students without a diagnosis to reach out regardless. They should help students navigate their potential disabilities and reach out to professors on behalf of students if needed.

Professors need to have a more unified consensus on accommodations, and while they work hard enough to support students, coming together and reviewing accommodation policies would be an immense help to students who have menstrual cycles. It can be anxiety-inducing going into a class not knowing if a professor will have a strict attendance or late work policy, or if they will be flexible and understanding.

For those with menstrual conditions, these worries increase tenfold. In general, one-third of female students have missed class due to painful periods, and many are reluctant to be honest about their absence. The stigma surrounding periods makes it so students are ashamed to give a valid excuse for missing class. Even if they were to be upfront, there is no guarantee that professors will be understanding of their issues.

The stigma around periods needs to change at the personal level, but it would be more effective if the rules of universities were to change first. Receiving more support and understanding from the institution they attend can help people with menstrual conditions feel secure and understood while navigating their health.

Menstrual health should be treated just as any other aspect of the human body. Treating it as a taboo or as a non-legitimate health concern will only lead to more people feeling lost within their own bodies. Starting a conversation with administrative powers like the ODS, being honest about our own menstrual health and encouraging others to educate themselves on menstrual health are some initial steps we can all take to begin empowering people who menstruate.

This story was written by Jenna Koch. She can be reached at jenna.koch@marquette.edu