In 2017, history professor Laura Matthew goes in search of local archives in Jacaltenango, Guatemala. Instead, she finds the larger-than-life legacy of Marquette alum and Maryknoll sister Dorothy Erickson, Class of ’52. Erickson is also known as Madre Rosa Cordis, the name she took as a Maryknoll novice. A few months later, students Francisco Hernández, Janet Peña, Luis Jiménez, Isabel Piedra and Ricardo Hernández begin a yearlong journey to understand why Madre Rosa is so beloved.

It starts in 1912.

In the town of Ossining, New York, the Maryknoll Order of global Catholic missionaries forms an order of religious women to serve the needs of impoverished communities around the world. Sister Mary Mercy Hirschboeck is the first Maryknoll doctor, graduating from Marquette Medical School — now the Medical College of Wisconsin — in 1927. She leads the Maryknoll Sisters to work in education, health care and pastoral ministry in places like Kenya, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, and in China, Japan, Korea and Cambodia.

Beginning in the 1950s, the Maryknolls begin to serve in Latin American countries like Peru, Ecuador and Guatemala. They arrive in the remote village of Jacaltenango, Guatemala, at a moment of political uncertainty and growing violence. In 1952, the Guatemalan Congress approves an agrarian reform law that expropriates land belonging to the U.S.-owned United Fruit Company.

In response, the United States denounces democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz as a communist and helps forcibly remove him from power. A new U.S.-backed president reverses Arbenz’s policies aimed at improving the lives of farmers, many of whom are indigenous Maya.

This political conflict sparks Guatemala’s 36-year civil war. For the next two decades, left-wing guerrilla groups fight against a series of military regimes. Maya communities such as Jacaltenango are targeted by both the guerrilla and the military as possible supporters of revolution. The resulting violence is marked by abductions, torture, and massacres of entire villages.

The violence is just beginning when over 30 Jakalteko men and 100 Jakalteka women sign two letters in December 1959, asking for a “nurse specializing in childbirth” and a doctor to help end maternal mortality in the village.

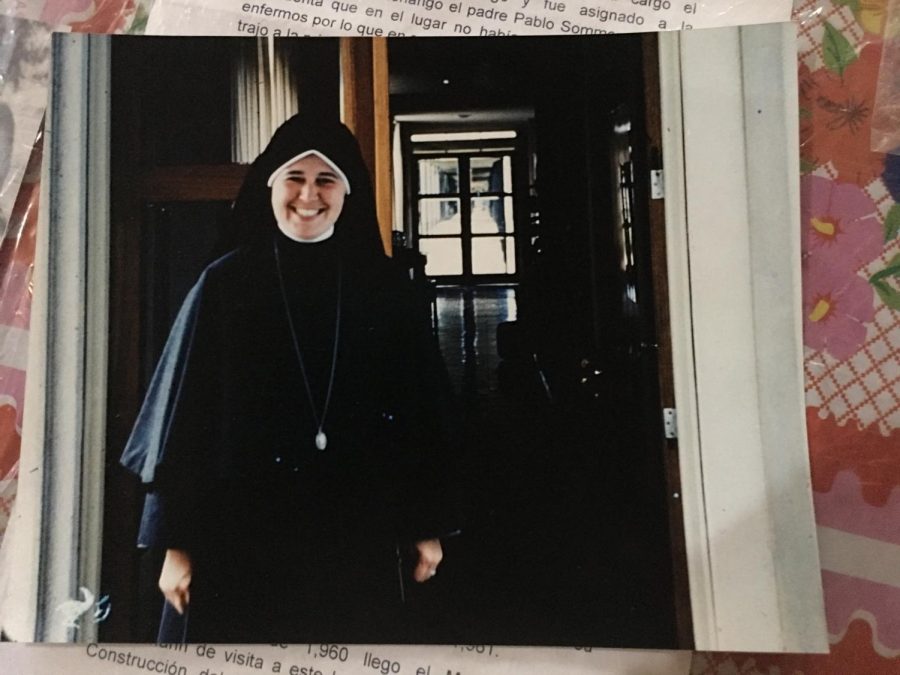

The Maryknolls’ answer is Dorothy Erickson, a Maryknoll sister and 1952 graduate of Marquette Medical School. She arrives in Jacaltenango in 1962 after a one-year internship in New York City and eight years in a rural Bolivian hospital. Jacaltenango, however, has no hospital nor even a clinic. Erickson, or Madre Rosa as the Jakaltekos call her, and the other Maryknoll sisters will have to build their hospital with the villagers from the ground up.

We get up early in the regional capital of Huehuetenango, and hop into a small, red sedan for a four-hour car ride to our final destination: Jacaltenango. I have the luxury of sitting the passenger seat – four others are squeezed in the back seat. The heat and constant curves take us up the Guatemalan mountains. While full of scenic beauty, the car ride puts transportation in Guatemala into perspective. I cannot even imagine the difficulty in an era before cars and the modern highway, yet this was the journey the Jakaltekos made to get medical care before Madre Rosa — Francisco Hernández, July 2018

Jane Buellesbach — a Maryknoll sister, medical doctor and native of Milwaukee — follows Madre Rosa to Jacaltenango in 1964. Sister Jane details the laborious construction of the hospital by the Maryknolls together with the Jakaltekos in a 1966 article published by The Linacre Quarterly called “Medicine by Muleback.” The difficulty of obtaining necessary, life-saving medical equipment to use at the hospital is followed by frustrations at not having a means to transport it efficiently. A main road has not been built. Even children are tasked with bringing a single brick to school each morning to order to attend their classes, their contribution to building the hospital.

I imagine the process of building the hospital as difficult, but nothing compares to hearing about it from the villagers themselves while sitting in the fruits of their labor. I can’t help but compare my prior knowledge of Madre Rosa from the Maryknoll archives in Ossining to all this new information pouring in from people that had many experiences with her. One of Madre Rosa’s nurse trainees, Juana Verónica Montejo, says that maternal mortality was something Madre Rosa took seriously, not only because she always strove to provide the best care possible, but because Madre Rosa lost her own mother due to complications of childbirth only a month after she was born. Madre Rosa tried to prevent anyone else from experiencing the same grief. To the Jakaltekos, Madre Rosa is a saint. — Janet Peña, July 2018

As the Guatemalan war heats up, Maryknoll Brothers Arthur and Thomas Melville; Maryknoll Sisters Marian Pahl, Catherine Sagan and Marjorie Bradford; and Maryknoll priest Blase Bonpane decide to join the guerrilla uprising. After years of political repression of democratic politics in the country, this group of Maryknolls forms a new organization of militant Christians. They dedicate themselves to defending the rights of the oppressed directly by supporting a revolt against the government. Though the Maryknoll guerrilleros do not commit any violent actions, their affiliation with the guerrilla leads to their suspension and excommunication.

The Guatemalan Civil War reaches its height during the 1980s when the military commits widespread massacres, profoundly impacting the country at its rural heart and disrupting daily life. Jacaltenango is occupied by the army in 1981. Two weeks after barracks are constructed, five men are kidnapped, and only two return home alive. Quickly, local military service becomes an obligation. Primary school students are trained to march during school. A building next to the church becomes a center of interrogation and torture. The violence becomes part of everyday life.

The Maryknolls have the option to leave the dangers of the conflict. But they decide to stay with their people in Guatemala and continue their work. Some feel that the core values of their order align with those of the guerrilla: to help the people. The Guatemalan military agrees and targets some Maryknolls for assassination. In Jacaltenango, however, Madre Rosa somehow keeps the hospital from being closed down.

As tensions mount, mistrust begins to rise among the Maryknolls themselves. Sister Mary Malherek, coordinator of the rural health program, travels to outlying villages to give courses in hygiene, but some Maryknolls express doubts about the health promoters’ program. Malherek feels as though she is being singled out for fraternizing with the guerrillas even though she is not connected to them. The Maryknolls live through the same crucible as the villagers.

One of our first opportunities to discuss Madre Rosa comes rather spontaneously. A group of women invite us to Madre Rosa’s memorial, a vibrant pink celebration of life. We sit on the steps to the tomb and converse in groups, using our phones as makeshift recorders. The women’s hospitality and kind spirits, the praise and happiness they express, solidify for me the impact of Madre Rosa and the hospital. It is incredible to be able to visit a place where one person has had such an impact on the lives of a community. — Isabel Piedra, July 2018

Madre Rosa and the Maryknolls stay with the Jakaltekos throughout the war until Madre Rosa’s death in 1994. Today, the hospital is run by a different religious order. But Madre Rosa remains. Her bust looks out over the church plaza. Her tomb towers over the cemetery. Her name graces the local secondary school. Most of all, Madre Rosa lives on in the hearts of the Jakaltekos and Jakaltekas, young and old, who shared their memories with us and still ask for her spirit to guide them.

Luis Jiménez and Ricardo Fernández contributed to this report.

This is a volunteered submission written by a group of Marquette students, who graduated December 2019.