“We really wanted to stay,” Morgan Schnabl says. “We loved that location … but after about two months, we realized ‘Dang. Well, it’s not really an option.'”

Schnabl is the owner of Milwaukee restaurant Brunch that was located along the Milwaukee riverfront at 800 North Plankinton Street.

The restaurant, dawned in blue paint and a big yellow yolk, has had problems with flooding for years, but was able to manage the water in the past. This past summer, the basement flooded and the city of Milwaukee told the employees food count no longer be served.

“The water just got too high and it’s something that we had battled with for a long time and once it got too high for us to operate anymore, we were forced to shut down,” Schnabl says.

Now at a location away from the river at 714 North Milwaukee Street, the restaurant lives on, but the memories of the flooding still remain.

The persistent flooding happens during the spring of 2019. The relocations occurs during the following summer.

The flooding is a result of a lack of infrastructure and improper precautions of those who owned the building Brunch occupied. Brunch had been at the Plankinton location since it opened in 2016.

Schnabl says neighboring businesses on Plankinton are able to keep water down with sump pumps, lift stations —which are housed below businesses and residences that collected waste water that is directed to a water treatment facility — and other systems. Brunch did not utilize those systems.

Rising river and lake levels is an effect climate change is having — and will continue to have — on the Greater Milwaukee Area.

Milwaukee Riverkeeper, a nonprofit organization that aims to ensure the health of Milwaukee’s water, notes Lake Michigan’s water levels have increased an unprecedented 12 inches per year for the last six years.

In 2013, the great lake reaches a record low. The water level was estimated to be at 576 feet, according to the Milwaukee Riverkeeper. But with increases in cumulative rain and snow, water levels are rising and are recorded higher than ever before. The Riverkeeper reports the lake has risen a little over six feet from six years ago, breaking its “high water record of 33 years.”

The river now resides at 582.18 feet.

Vince Bushell, a field staff member at the River Revitalization Foundation, says he has seen changing lake levels impact his work for the Milwaukee River. The River Revitalization Foundation empowers people to protect and restore water while its mission is to “establish an urban parkway for public access, walkways, recreation and education, bordering the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnicikinnic Rivers” to revitalize and improve water quality.

The Milwaukee River, which acts as an estuary, or where the river stream meets the tide of the lake, has risen largely due to an increase in yearly rainfall, Bushell says. Bushell looks to the extreme rain events, or disproportionate amounts of rain in the city over the course the years 2008 and 2010. Measurements from October to September of all rain, snow and rain snow mix is totaled.

The rain events were predicted to happen 50 to 100 years apart, not two years.

“That gives you an indication that it might be more climate than just weather” Bushell says.

In 2008, approximately 43 inches of cumulative precipitation in Milwaukee was totaled. In 2010, 41 total inches were measured, surpassing Milwaukee’s average of 34.5 inches cumulative precipitation per year from 1981-2010, according to the Wisconsin State Climatology Office.

Forty-two inches of precipitation was received in 2018 and 44.5 inches in 2019 for Milwaukee. Bushell says this rainfall is combated by an underground system that catches wastewater and stormwater, which is called the deep tunnel. It cleans water and prevents it from polluting Lake Michigan. However, if rainfall continues to far surpass averages, Bushell says it will create issues for the Sewerage District, a regional government agency that provides water reclamation and flood management services.

In its 2019 Resilience Plan, which outlines resilience challenges and plans to combat them, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District notes Milwaukee region storms beginning in 2000 and extending through 2018 has caused significant flooding, basement backups, and sewerage overflows that has caused millions of dollars in damage across the area.

The existing grey infrastructure, or man-made water transportation and storage systems that work to move and store stormwater, the city has is not designed for larger storms like those that happened during that time frame.

It’s the same infrastructure that plays a part in the flooding at Brunch. However, Schnabl says there is not much the city could do, saying “(the city) places orders on the building to have the foundation repaired so that we could operate and would not allow us to operate again until those fixes were made.”

Schnabl says it is a positive thing for Brunch to be in a bigger, better location in the long run. Yet, that did not come without its challenges to move.

“Money-wise, we lost over half a million dollars and we’ll never get that back,” Schnabl says. “It was a very, very hard summer for us, we were shut down for four months. And we’re a high value, popular restaurant, which is great. Until it shuts down. After that, you realize how quickly funds dwindle.”

The Milwaukee Common Council approved a Green Infrastructure Plan released by the City of Milwaukee in June 2019. It is an effort to combat issues like flooding and also invest in green infrastructure and renewable energy. Most recently, the Milwaukee Common Council’s Public Works Committee voted to confirm the city’s largest solar energy project in history.

This project was voted on again and confirmed by the full Common Council March 3. It will be completed in collaboration with We Energies.

Erick Shambarger, the city’s Director of Environmental Sustainability, emphasizes that Milwaukee is committed to implementing green solutions in a number of places. One particularly exciting switch, Shambarger says, is happening at Milwaukee Public Schools.

“Every year we’re working with five schools and removing blacktops and putting in green space for kids to play on, which also manages stormwater,” Shambarger says. Green schoolyards help to reduce flooding by removing pavement, too much of which can trap water and overwhelm the existing grey infrastructure.

Shambarger makes aware of the Commercial Green Lot Grants Program, where up to $25,000 can be provided by the city towards the design or implementation of green infrastructure. Organizations can fill out an application and submit other tax documents and forms as indicated by the program website. The program is set to begin in 2020 and the Review Committee will determine which projects to allocate funding to.

The Hop streetcar, which began operation Nov. 2018, is another new development the city has taken in widening public transportation options. By using electric energy, The Hop reduces reliance on traditional fossil fuel vehicles.

The city has a goal of cutting energy use in overall city operations 20% over the next decade, Shambarger says.

Along with an increase flooding and cumulative precipitation, temperatures in Milwaukee are expecting to shift due to climate change.

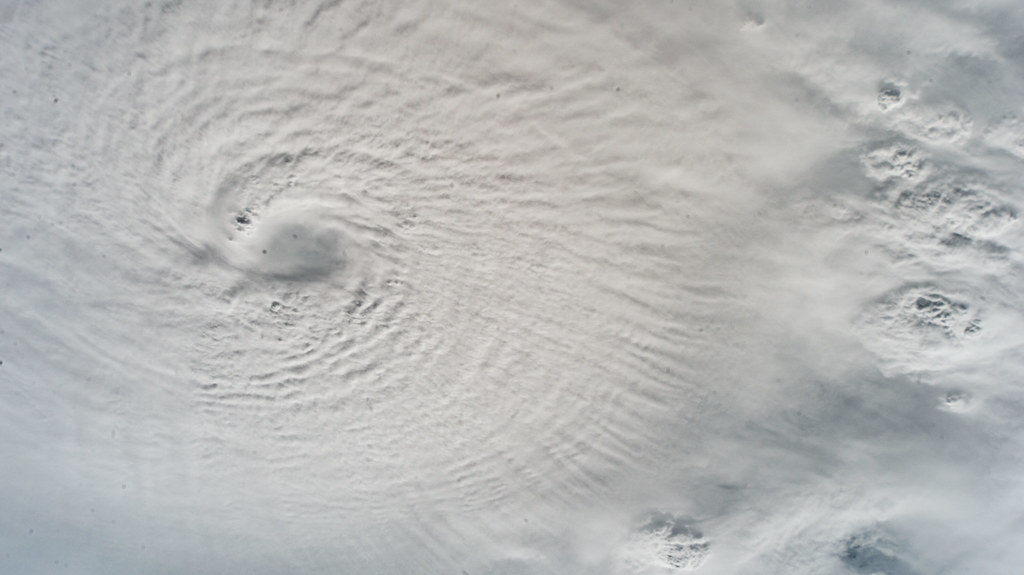

Stefan Schnitzer, chair of Marquette University’s environmental studies department, says Milwaukee will likely have hotter summers and winters that will bring abnormally cold and warm periods. Overall, variability in weather events such as hurricanes and tornadoes, is going to increase, Schnitzer says.

Schnitzer says Milwaukee, and the Midwest as a whole, is relatively buffered from some of the more drastic effects of climate change due to its region, as the natural lay of the region and its distance from the oceans offer a layer of relative protection.

“The West Coast is going to suffer greatly from drought, the East Coast and the Southeast are going to get slammed by hurricanes…Milwaukee is kind of in this more stable area,” Schnitzer says.

One major impact that Milwaukee, and many cities, will face is the urban heat island effect.

Anthony Parolari, assistant professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at Marquette, says an urban heat island is a city which tends to be hotter than its surrounding areas.

With summer temperatures in the city averaging about 1.4 degrees higher than the rural areas, the city of Milwaukee can be up to 18 degrees hotter than surrounding rural areas, according to Climate Central.

Parolari says this is because the dark surfaces placed in the city absorb more sunlight, which increases heat. Additionally, the high number of cars and headed buildings add to the urban heat island effect.

Parolari says that fellow Marquette faculty are working to produce energy from sewage by creating methane, which is recycling energy, as well as extracting nutrients from waste streams. Parolari himself works on creating green infrastructure such as green roofs to offset the urban heat island and capturing pollutants from stormwater to reduce flooding.

Parolari notes the urban heat island effect will disproportionately impact economically disadvantaged areas, as they tend to have less vegetation to block sunlight from pavement.

Schnitzer says affected individuals are also likely to have less access to air conditioning.

“When temperatures get really high, people die,” Schnitzer says.

Bushell says environmental scientists are using cloned plants — grown from clippings or seeds of existing plants genetically identical to them — to test variation in temperatures, planting them at different distances north and south of equator. Because cloned plants do not have the genetic capacity to adapt to new weather situations, they are used as an ecological method of gauging temperature increase, as they will die if the temperature is not suitable.

While the River Revitalization Foundation is not currently participating in this study of cloned plants, Bushell notes that the foundation plants Ohio Buckeyes and Redbuds, both non-native trees, because they survive better in hot weather, which helps ensure there will be plant life in the area that can outlast the increased temperatures. Since these trees are not clones, Bushell says, they will have a chance to potentially adapt and survive in new weather conditions.

Schnitzer is studying tropical forests in Panama and says tropical forests have a major effect on carbon. Forests store about 40% of the world’s carbon produced by life on land. As climate change progresses, tropical forests are storing less carbon. Trees are one of the reservoirs that participate in the carbon cycle.

Schnitzer and his team of researchers are working on large-scale predictions surrounding what this will mean for global warming, the effects of which will reach Milwaukee and the rest of the planet.

Joe Wilson, executive director of Keep Greater Milwaukee Beautiful, says education about the environment is essential. He says the organization focuses on taking the climate as it is and working to improve it.

Wilson, and the rest of the organization, provides information to students in local schools about pollution and sustainability. One example of this is in their discussion of farming, an issue directly relevant to Milwaukee and its proximity to the state’s agriculture industry.

“We see that crops and farmers are all challenged with growing things and, you know, the condition of the soil, the condition of lack of rain or too much rain or whatever it might be,” Wilson says. “We work then to show people how to be better urban farmers, how to be more sustainable and not rely on some of the crops that may not have a good year.”

For students to combat climate change in their own lives, Wilson says to carpool, use reusable bags and buy in bulk, as those are some actionable solutions.

“Students ought to look at organizations that do things like plant trees, clean rivers, that really need their effort, that come and help stall the problem of people polluting…but also passing the word along to people that they should recycle, that they should be involved in organizations that help teach younger people about it so they could come and read to them or make visits,” Wilson says.

Parolari emphasizes the importance of making green choices, but acknowledges the accessibility issues it raises. He says that one of his friends recently bought an electric car, but not everyone can afford steps like this. The average price of a new gasoline-powered four-door sedan is $35,000, while the average price for electrics cars are $55,000.

However, the responsibility to help the environment does not lie entirely on individuals.

“We are only going to address these problems as quickly as our leadership recognizes them and addresses them,” Parolari says. He emphasizes the dual perspectives on combating climate change.

Focusing on electing officials who will listen and develop the necessary policies while also doing what you can in your daily life, is what Parolari says will help move us in the right direction.