This past weekend, Milwaukee hosted a film festival that was the first of its kind not only in the city, but in the United States.

The Minority Health Film Festival, which ran Sept. 12-15, was the country’s first film festival created to address the topic, said Heidi Moore, director of emerging markets and inclusion at Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin and one of the festival’s organizers.

The festival featured films and speakers that addressed topics of mental and physical health specifically regarding minority communities. The festival showed eight different films at the Oriental Theatre, each followed by a panel discussion.

Beyond film, there were three featured speakers and 11 panel discussions hosted at different locations across the city, including Turner Hall Ballroom, Kenilworth Square East Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Union Ballroom East and The Back Room @ Colectivo.

Among the speakers at the post-film talkbacks were president and co-founder of REDgen Amy Lovell, who was one of five panelists following the showing of the film “Resilience”; Sumana Chattopadhyay, an associate professor in the College of Communication, who moderated the discussion following the film “Unbroken Glass”; and Dora Clayton-Jones, an assistant professor in the College of Nursing, who participated in the talkback after “Spilled Milk.”

REDgen is an organization aimed to raise mental health awareness and promote general well-being of youth in all communities. The name means “resiliency education determined to make a difference in the health of a new generation.”

The group formed in 2013 after several youths died by suicide in the North Shore area of Milwaukee. One of those who died was a close friend of Lovell’s daughter.

Lovell said REDgen has shown the film “Resilience” multiple times. She said the film inspired her to address trauma in Milwaukee.

As a result, Lovell helped create Scaling Wellness in Milwaukee in 2018. SWIM aims to create a community supportive of victims of trauma, according to its website. Studies show widespread neurological trauma is a root cause of much of the unemployment, homelessness, addiction and mental illness in cities such as Milwaukee. SWIM is currently applying to be a nonprofit, Lovell said.

“Resilience” analyzes the Adverse Childhood Experience Study, a survey done in the 90s that asked participants to answer 10 yes-or-no questions about whether they had certain traumatic experiences before their 18th birthdays. The study reflected that individuals who answered “yes” to more questions on the survey had higher rates of health issues including diabetes, heart disease, addiction, mental illness and higher likelihood of death by suicide, Lovell said.

“Loving relationships and people caring can make a big difference and help promote resiliency in people’s lives,” Lovell said. “Like, that’s one thing that the science has proven, is that if children experience adversity but they have buffering adults in their life, they can develop resilience and come through it.”

Other films focused on specific experiences of individuals.

“Unbroken Glass” tells the personal story of director Dinesh Das Sabu’s journey to understand his family’s history. When he was six years old, Das Sabu lost both his parents — first his father to stomach cancer, then his mother, who suffered from schizophrenia, to suicide. Das Sabu is the youngest of five. His two older sisters, 21 and 16 years old when their parents passed away, raised him and his two brothers.

Chattopadhyay moderated the discussion panel featuring Das Sabu and two Asian American mental health professionals after the screening. The discussion addressed the theme of mental health stigmas, particularly viewed through a cultural lens.

“This film started as basically just an excuse to have a lot of really hard conversations,” Sabu said during the panel.

In the documentary, Das Sabu travels to India, interviews many family members and works to uncover buried family history.

Das Sabu said interviews with his aunt and uncle did not make it into the documentary because his aunt became nervous and chose not to sign the release form.

Both his aunt and uncle were doctors in India and provided valuable insights about mental health as well as family memories, Das Sabu said. However, his aunt refused to sign the release form because not only did her sons not know how Das Sabu’s mother died, but she feared her sons’ wives’ families would find out.

Despite this, Das Sabu said when the documentary came out a few years later, those relatives did see the film and “loved it.” Mental illness, particularly in Indian and immigrant cultures, often carries a stigma that results in silence, secrets and shame, the panel reflected. Das Sabu said sharing the story has helped eliminate that stigma.

Chattopadhyay said she was asked to moderate the panel because she has experience teaching classes at Marquette that focused on social campaigns and mental health and additionally because she comes from an Indian family.

Another film driven by personal experience is Jaqai Mickelson’s “Spilled Milk.” The documentary addresses the issue of sickle cell disease. The disease, Clayton-Jones said, is a genetic abnormality that causes blood cells to be sickle shaped. It causes complications of “traffic jams of cells” which can result in pain and severe health risks.

Mickelson documents his best friend Omar’s experience living with the disease in an effort to spread awareness of the affliction which in the United States primarily affects African American populations.

While sickle cell disease is rare, it is still one of the most common inherited genetic diseases, Clayton-Jones said, and is not widely known among health professionals in the United States.

It was Clayton-Jones’s idea to bring the film to Milwaukee. As president of the International Association of Sickle Cell Nurses and Professional Associates, Clayton-Jones said she feels passionate about spreading awareness of the disease, which afflicts a population that “suffers from an incredible amount of stigma and social injustice.”

Clayton-Jones suggested airing the documentary to Moore and Monique Graham, the director of community engagement at Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin, unaware that they were already in the process of putting together a film festival focusing on the very topic “Spilled Milk” addresses: health and minority communities. Fittingly, Clayton-Jones said, September is Sickle Cell Awareness Month.

Clayton-Jones participated in the discussion panel after the film, and Marquette officially sponsored the “Spilled Milk” showing.

While the Minority Health Film Festival addressed a variety of health issues involving a variety of communities, many of the films and discussions shared a common theme: hope.

Clayton-Jones said the festival takes topics not often addressed and promotes conversation about them.

“Sometimes it takes events like this for us to reflect and for us to have discussions,” Clayton-Jones said. “My hope is that whatever film that individuals are watching, that they will take that back to their families, to their workplaces, to their community and have some discussions.”

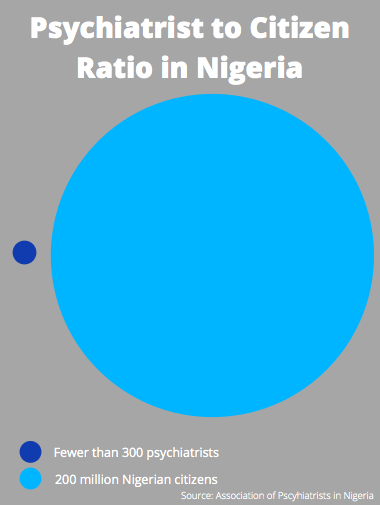

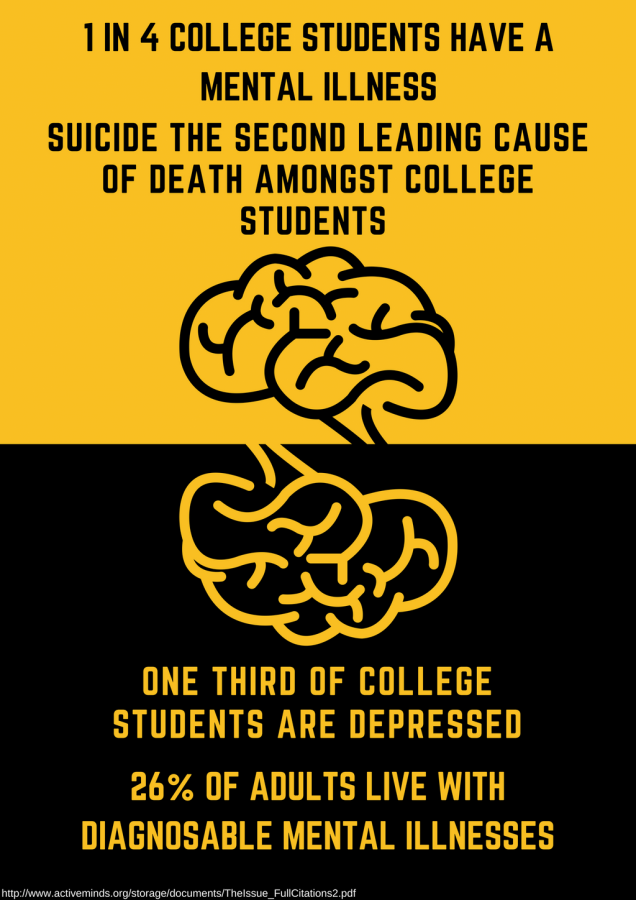

Lovell said discussions generated by the festival can help draw attention to resource disparities and promote action.

“There’s no boundary for … mental health challenges,” Lovell said. “There’s no boundary. It happens everywhere. But … there’s inequity in our resources, and so I think it’s important for people to see the impact this has across all people in our community, and hopefully people will want to work toward bringing more equity and fairness in the resources.”

Harold A Maio • Sep 18, 2019 at 4:09 am

I wonder why we so easily accept those who say there is a stigma to mental illnesses? Why do we so readily yield authority to them?