In the United States, more than 2.3 million people are incarcerated in state prisons, federal prisons and local jails. The case Estelle v. Gamble in 1976 was a landmark decision, which ruled that not providing adequate care to prisoners violated their Eighth Amendment rights. Unfortunately, the health care system in prisons does not meet this standard and needs immediate reforms.

At least 35 states still allow prisons to charge copayments to inmates, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. The Federal Bureau of Prisons is the institution that allows prisons to charge copayments, which is extremely unfair.

Many people in prison come from impoverished backgrounds. The median income of those involved with the justice system is about 41 percent lower than those not involved with the system, according to a 2015 report from the Prison Policy Initiative.

In addition to that, inmates are underpaid. Prison Policy Initiative said the average wage is about 86 cents per hour. If inmates are required to make copayments in order to receive medical attention, they may decide to forgo necessary medical treatment in order to buy other necessities, like soap or food.

In most prisons, inmates are also responsible for paying for medicine prescribed by a doctor. For example, Tylenol, topical cream or allergy care have to be purchased by inmates using their commissary funds. Commissary is the store within prisons where inmates can spend their wages or money their family sends them. This can be a big hit to the inmates’ incomes.

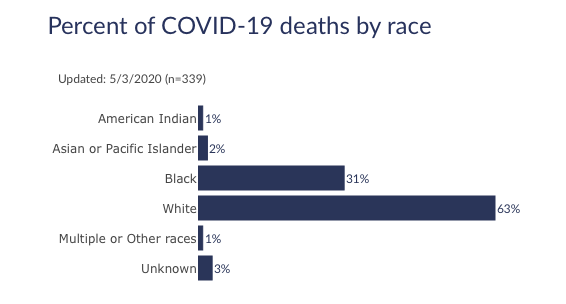

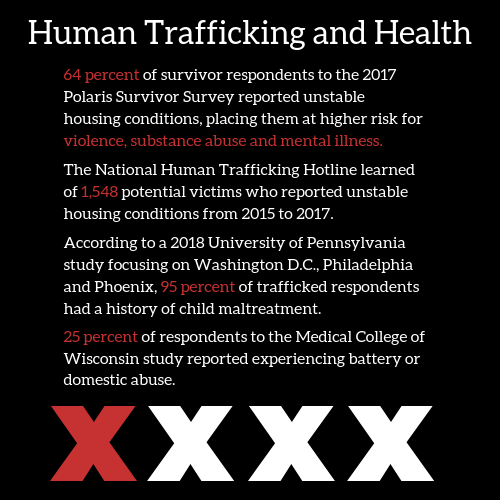

As a result of too few doctors and nurses, many inmates medical treatment is delayed or outright denied. In addition, many inmates struggle with mental health issues. More than 1.2 million people in prison suffer from mental illness according to Mental Health America. Sickness may be more common due to poor diet and unclean living conditions. Inmates have no control over these factors, so it is all too important that health care professionals are in place to help combat this. Diseases also spread through crowded prisons quickly and easily.

One place that is doing health care right is the Bernalillo County Metropolitan Detention Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Inmates have the ability to see nurses on a walk-in basis, compared to other prisons where inmates must submit a written request. Phillip Greer, chief of corrections at the institution, said in an article, copayments are a way to keep inmates from misusing the system. Typically, inmates pay $3 for a nurse visit and $5 for a doctor’s visit. But prisoners are not denied service if they cannot pay.

A study by the American Journal of Public Health in 2009 revealed that 68 percent of local jail inmates and 14 percent of federal prison inmates with chronic medical problems don’t receive a medical exam while incarcerated. The fact that prisoners are being denied basic human rights highlights how those who are incarcerated are viewed differently by society.

Another negative consequence inmates face is long waiting lists to see doctors. Because of extreme overcrowding in prisons, it is impossible to get inmates access to immediate medical attention, even if it is urgent and necessary. Inmates may be forced to endure long waiting lists to see a doctor even about something as simple as a cough.

It is essential that the health care system in prison be reformed to satisfy basic human rights.