More than $60 million in campaign contributions have gone to gubernatorial candidates Scott Walker and Tony Evers, Senate candidates Tammy Baldwin and Leah Vukmir and 4th Congressional District candidate Gwen Moore in the state’s midterm election cycle.

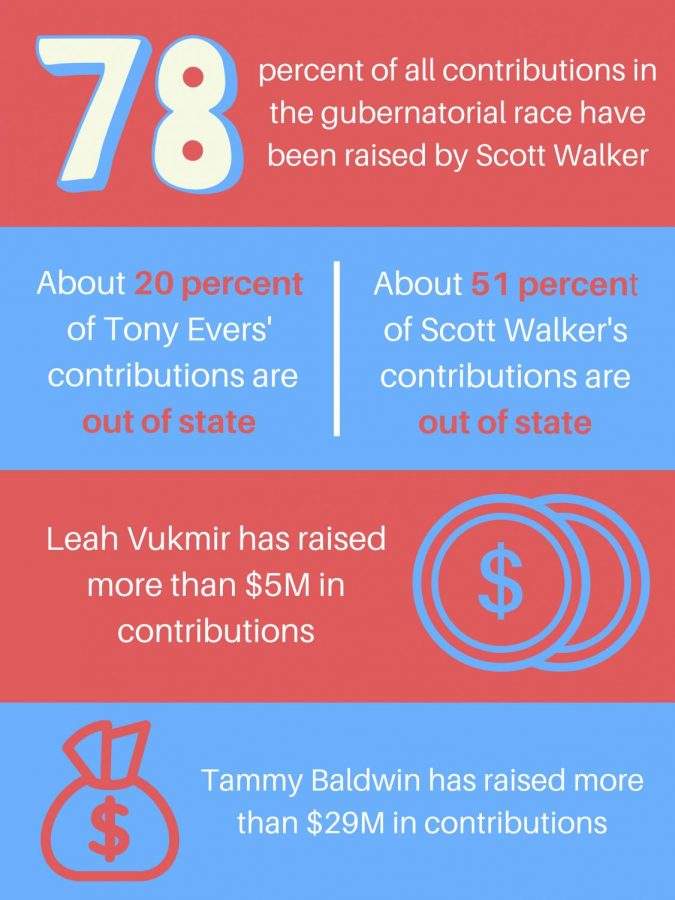

Incumbent Gov. Walker raised nearly $24 million in campaign contributions as of Oct. 16, according to data from the Wisconsin Campaign Finance Information System. The same data indicated that Democratic challenger Evers raised nearly $3 million in campaign contributions.

In elections, incumbents tend to raise and spend more money than newcomers, Hong Min Park, an associate professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, said.

He said incumbents have greater access to potential donors, existing relationships with past donors and an office position that allows them to provide benefits to donors.

“Those donors giving more amounts are more transactional in nature,” Sheila Krumholz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, said.

Incumbents can take advantage of the franking privilege, which allows current officeholders to send official mail to constituents without paying postage fees.

“If you’re an incumbent member of Congress … what they tend to do is raise money throughout their time in office, so they don’t really take a break from the electoral process throughout the course of their term,” Christopher Murray, a visiting instructor and coordinator of student programs for the Les Aspin Center for Government, said.

Incumbents who spend more money can face higher chances of losing elections, Park said.

“That’s a sign of weakness rather than strength,” Park said. “When the campaign is not going well, that means the election is very competitive with a qualified challenger.”

Sources of money differ depending on candidates’ party affiliations, Murray said. He said Democratic candidates typically raise more money from unions, while Republican candidates usually yield more from business groups. With a House win possible for the Democrats Nov. 6, Murray said the party has received more business donations than usual.

Out-of-state donations also play a large role in elections, with more than half of Walker’s contributions coming from outside Wisconsin. About 20 percent of Evers’ contributions came from other states.

These contributions are often coordinated by party organizations to strategically input money in specific districts, Park said. He said this is done in an effort to increase the party candidate’s chance of winning.

“Out-of-state donations are tricky because they can provide much-needed support, and yet it can present the illusion of popular support,” Krumholz said. “But those donors can’t do much for the candidate on Election Day when it counts. You can have all the money in the world, but if you don’t have votes, you’re going to lose.”

Krumholz said out-of-state support can backfire on candidates if constituents feel like outsiders are trying to meddle in the election.

Candidates with national profiles can attract donations from outside the state, Murray said. He said Walker’s past run for president in the 2016 election elevated his recognition across state lines.

“He may run for president in the future,” Murray said. “He’s somebody that Republicans get excited about in terms of how he’s run the state of Wisconsin, so they may donate to him regardless of where they live.”

Murray also noted Democratic incumbent Sen. Baldwin’s nationalized race, with out-of-state individuals and groups donating to her in support of pro-LGBTQ policies.

Baldwin has raised more than $29 million this election cycle, while Republican challenger Vukmir has raised more than $5 million, according to data from the Federal Election Commission aggregated by the Center for Responsive Politics. About 60 percent of Baldwin’s donations are from out of state, compared to nearly 32 percent of Vukmir’s donations.

Murray said Senate races tend to garner more attention than House races. While senators get elected every six years, House members serve two-year terms. Murray also said senators represent larger constituencies, and those races attract more qualified candidates.

“Senators represent entire states,” Murray said. “That’s a much larger audience that candidates need to reach, which means that it’s going to be more expensive, and especially in bigger states.”

District 4 congressional representative Moore, a Democratic incumbent without a challenger, has raised $943,769 in contributions.

While television, radio and print advertising remain traditional tactics candidates employ, online advertising and social media messaging has emerged in recent years, Murray said.

“If they are a good candidate and they have a really compelling message, what they’re also able to take advantage of are social media tools which are really inexpensive ways to reach potential donors,” Murray said.

Outside groups, such as interest groups, political action committees and super PACs, have also played a larger role in recent elections. As long as these groups do not directly coordinate spending activities with candidates, they can spend as much as they want on advertisements on behalf of candidates, Murray said.

However, outside groups can lack true independence, Krumholz said.

“They can be set up by my former chief of staff or my dad, my mom,” Krumholz said. “Then they act basically as extensions of the campaign.”

Despite the influence of these outside groups, Murray said campaign spending has been having a smaller impact on voters over the years. He said most voters are consistent in their party support, lessening money’s effect in today’s political climate.

“A lot of it is basically not doing anything to change the minds of voters,” Murray said. “The return on that spending is getting smaller and smaller and smaller.”

Money spent can make a difference in tight races, Murray said. This can be seen in the governor’s race, where Walker has 47 percent support and Evers has 46 percent support among likely voters, according to the Marquette Law School Poll.

“I don’t think people realize money’s influence when they make a decision in a voting booth,” Park said.

Krumholz said whether they realize it, money certainly affects voters.

“Money isn’t a panacea for a bad candidate,” Krumholz said. “But you can’t win without it.”