Waiting.

When it comes to finding affordable mental health care, the word comes up quite often. Sometimes, it is waiting in line at a public access clinic and other times, it’s waiting to hear if a screening has come back positive. And when you’re waiting for help with depression and anxiety, the wait can feel like a lifetime.

Marquette students are not immune to this. Many of them are on their own for the first time, trying to navigate the bureaucracy and red tape of health insurance or lack thereof. The process can be complex, confusing and intimidating. Sometimes, many students in these situations believe they have to go through it alone. People like Nick Jenkins, a counselor at Marquette’s Counseling Center, want students to know that there are people there to help.

The first step for somebody who does not have insurance is to visit the Counseling Center, Jenkins says. The Counseling Center provides services to students regardless of their insurance on a brief model basis, meaning that they only have the staff and resources to provide base-level services Jenkins says that various factors can affect the number of visits a student makes to the center, including treatment history and the specific issues that a student has. It helps refer students to other services, and in some cases, can even help uninsured students acquire insurance. Jenkins says that most students do not know what resources are available.

“Once someone is on campus and living here they are Milwaukee residents,” Jenkins says. “They can access services through Milwaukee County Behavioral Health.”

For people who are struggling with depression, Milwaukee County does offer an alternative option for assistance: the Warmline. The Warmline is a phone service geared towards giving people with depression quicker access to counseling and assistance. It can be reached at 414-777-4729. For urgent needs, the Psychiatric Crisis line can be reached at 414-257-7765.

Jenkins says the Access Clinic, a mental health clinic located on 9945 Watertown Plank Road, serves uninsured patients on a sliding fee scale and is one of the best places to go to find long-term mental health care. They cannot refuse service to anyone and can provide counseling on site, while also referring people to low-cost or free services tailored to their specific needs. The site generally has a long waitlist, however.

Some of the places someone might get referred to include the Wisconsin School of Professional Psychology for counseling and the Healing Center for treatment with an emphasis on sexual abuse, violence and trauma. There are also organizations such as Jewish Family Services and Aurora Family Services which, despite their names, offer individual counseling at low rates.

One of the places that offers low-cost services is the Columbia St. Mary’s Center for Psychotherapies on the east side, an extension of the Medical College of Wisconsin. The Center was founded by Dr. Carlyle Chan in 1982. It is a training clinic that hosts about 25 psychology residents at a time. It, too, can develop a waitlist.

“We can get backed up around the end of the academic year,” Chan says. “That’s when we’re in transition, bringing in new residents.”

The Center for Psychotherapies offers a base rate of $30 for their services and full diagnostic testing for $80 (Chan says diagnostic testing is usually hundreds of dollars at other sites). The center also has full screenings available by phone. The center averages between 6,000 and 7,000 visits a year.

Chan and his team provide advanced care for depression, anxiety and panic attacks, among other things. The vast majority of their client base is uninsured or seeking low-cost options. Chan says that the root of the problem is allocation of scarce resources, and that more could be done.

“It’s a tragedy that there aren’t more providers,” Chan says. “What we provide is vital to people.”

For those who do not want to leave Marquette’s campus, however, there is a resource that seems to be relatively unknown among students: the Center for Psychological Services.

James Hoelzle is the director of the Center for Psychological Services, a facility located on the third floor of Cramer Hall. Hoelzle says that people come from as far as Illinois and central Wisconsin for consultations and research. Despite that, the center remains one of Marquette’s best-kept secrets.

“That’s partially by design,” Hoelzle says. “We’re usually at or near capacity for most of the year. If more people knew about us, we’d have a longer waitlist.”

Hoelzle says that he would want to provide services for more students, but the center does not generate the revenue necessary for expansion. For the most part, the center is on its own financially. Hoelzle says providing free therapy sessions and consultations does not bring in much money, but he wouldn’t compromise providing low-cost care for students.

“I take great pride in the work that is done here,” Hoelzle says.

Hoelzle says the split between students and members of the larger community is about 50-50. In order to access the CPS, clients fill out an intake packet that allows staff to begin treatment or refer them to other services that may be more appropriate.

“I don’t think we’re a sustainable solution on our own,” Hoelzle says. “We’re just a piece of the puzzle.”

There is generally a waitlist at the CPS. The graduate students employed there are working on a regular semester schedule, which means it is easier to access services earlier in the semester before classes ramp up toward the end. However, once clients are paired up with their providers, the staff at the CPS makes sure that appointments and engagements are honored.

Waitlists are a significant problem across all facets of health, but mental health has its own unique challenges. People who urgently need care are often bumped up on waiting lists, which alternatively bumps other patients down due to a lack of other resources being available. Due to the complex nature of mental health, many people are not fully cured which causes clinics to remain open to return visits, once again driving names further down the lists.

While Jenkins says he believes that there are quality healthcare options for people without health insurance, he also strongly urges students who have a permanent residence in Milwaukee to look into applying for Badgercare. The Counseling Center has facilitated many students’ applications for Badgercare, and they plan to continue doing so.

“Oftentimes they can find someone who is a good fit, but I think that’s also less of their choice and more limited by what’s available,” Jenkins says of uninsured patients. “Once you have insurance, you have more ability to say is this person a good fit for me for counseling and does this work out.”

Efforts have continued in Congress to try and achieve more parity for mental health insurance, meaning if someone receives general health insurance from their employer, they must also receive equal coverage for mental health insurance. In 2008, the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act was passed, providing increased parity for people who receive insurance via their employer and recipients of insurance options such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program and Affordable Care Act programs. In other words, if an insurer charges a $20 copay for a typical general health visit, this law stipulates that insurers cannot charge any more than a $20 copay for mental health visits. The Department of Labor estimates that 40 million, one in five, adults in America benefit from MHPAEA.

Had it passed, the 2017 GOP-proposed American Health Care Act would have derailed the program significantly by restricting enrollment to the aforementioned programs. It also would have allowed states to potentially skirt parity regulations. The American Psychological Association estimates that 90 percent of Americans are unaware of the law and its effects.

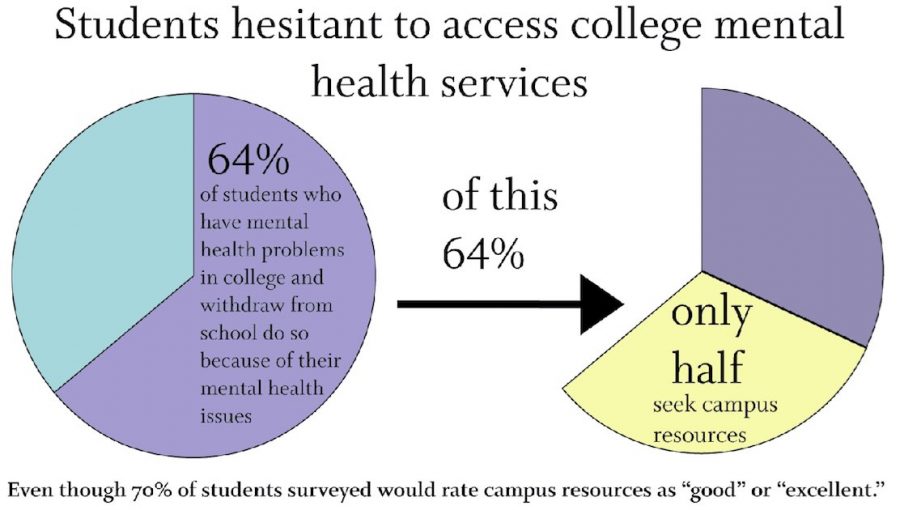

One of the biggest struggles that the Counseling Center and the mental health field at large still face is stigmatization of services.

“I think a lot of people think that going to counseling means ‘I’m crazy,’ which is just not true,” Jenkins says. “People come in for anxiety, anxiety about school, anxiety about financial issues, mood issues; stuff that affects us all. Issues after a breakup, when we lose somebody, when we struggle with our direction in our career. These are all very normal things.”

According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, about half of all Americans will obtain mental health services in their lifetime. Jenkins says that the Counseling Center is in constant conversation on how to address cultural and social barriers so people can receive the help they need.

“I hope that people, especially when they’re struggling, just know that there’s places to talk, there are people here to help out and we’re trying as best we can to help them,” Jenkins says.