Women accounted for nearly 28 percent of the workforce in science and engineering careers in 2015, according to the National Science Foundation. From 2005-’13, females consistently accounted for about 40 percent of all STEM majors at Marquette, according to the Office of Institutional Research and Analysis. That number has grown six percentage points in the past four years.

Julie Murphy, the director of enrollment management and outreach for the College of Engineering, said though Marquette’s male to female ratio in STEM majors is less disproportionate than in the workforce, many women interested in STEM exit the field between school and job searching.

“It’s a struggle in the classroom. It’s a struggle at the college level. It’s a struggle in the industry, as well,” Murphy said.

To combat these challenges, Murphy’s department hosts a few pre-college summer programs aimed at female high school students. At the college level, the issue is addressed through interactive sessions with Kristina Ropella, the dean of the College of Engineering.

One session consisted of a focus group in which female engineering students shared their opinions on the college’s relationship with women in STEM. Murphy said some students identified challenges with class dynamics.

“When you’re in groups, being assumed that you will be the notetaker, being assumed that you will do the secretarial work as opposed to the more challenging math of the group, the organizer of the group, the mom of the group,” Murphy said.

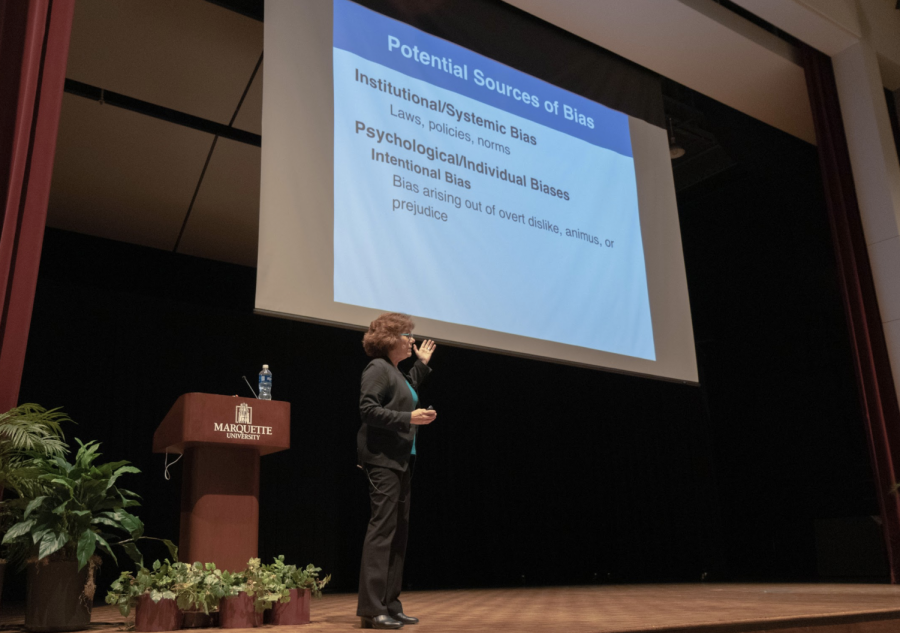

The Women in STEM Summit was held all day in the Alumni Memorial Union Ballrooms April 23. The Marquette Women’s Innovation Network and the Women’s Colleague Program put on the event as a partnership between Marquette and Johnson Controls.

The summit featured several prominent local women in STEM, including Ropella and Adonica Randall, a Marquette alumna and the College of Engineering entrepreneur-in-residence.

In her opening remarks at the summit, Ropella told the audience to “celebrate triumphs and victories,” while reminding them to encourage young girls to pursue futures in STEM.

Murphy agreed that early outreach is key because middle school classes set the path for the level of math students can attain in the long run. She said girls turn away from engineering while in middle school because they do not pursue the highest-level math track they can, or should, to be ready for engineering after high school.

“It’s not that they can’t make that up, but if you’re graduating and you have not had calculus or pre-calculus, that happened in middle school,” she said.

It’s impossible to know what directly causes this trend, Murphy said. One possibility is a lack of role models in the field.

“Middle school is a prime time to have role models, and we don’t,” she said. “There’s just this bias that we all have that I think we have to continue to fight against. Women are smart. We are capable — just as capable as men. Sometimes more so, frankly.”

Some women looked on-screen to find a role model. For Randall, that person was Nichelle Nichols, or Lieutenant Uhura on the television show “Star Trek,” which aired during the ’60s when she was growing up.

“Do you know how exciting that was for somebody young wanting to see somebody who looks like you — to grow up and see the figure of a woman who had a position of authority on a starship deck?” Randall said. “I wanted to do it because I wanted to not be common. I didn’t want the small aspirations that other people had. I wanted to be sitting on the deck of that starship.”

Alex Solecki, a freshman in the College of Engineering, said although she is outnumbered by males in all of her classes, she is encouraged by her mother.

“I never was really fixated on how male-dominant the field of engineering was. From a young age, (my mom) always encouraged me to do what I thought would make a difference, no matter what field,” she said.

Solecki said her goal is not to make girls feel pressured to enter careers in STEM.

“It’s about making sure that young women know that they are just as capable of and just as welcome to pursue whatever it is that they are drawn to — be it art, science, math, history, whatever,” Solecki said. “A valid first step is to show them that STEM is not just a man’s world. The more we de-gender learning, the more we’re opening up the next generation (helps us) bring the most driven and passionate people into the places they feel like they belong.”

Murphy said efforts to encourage women to pursue STEM are for the betterment of more than just women.

“You get a diverse group of people together, and your end product is going to be stronger every time,” Murphy said. “We all bring different lenses. Women see the world differently than men see the world, and they’re able to contribute differently.”