Sexual assault on college campuses is pervasive. The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network reports 11.2 percent of all students have experienced some form of sexual violence, and a study published in the academic journal Violence and Victims found that 63 percent of rapists were repeat offenders.

But sexual assault doesn’t begin in college. A 2013 study by JAMA Pediatrics reported that one in 10 young adults between the ages of 14 and 21 have pursued nonconsensual sexual behavior, and 50 percent of those perpetrators said it was the victim’s fault. The study also reported that most perpetrators committed their first assault by age 16.

Despite this data, consent is rarely discussed in high school or middle school. A survey by Planned Parenthood Federation of America reports that only 14 percent of respondents said they had learned about consent in middle school, and only 21 percent said they had learned in high school.

The failure to consistently educate on sexual violence contributes to a society that at worst excuses instances of sexual misconduct, and at best fails to prioritize its prevention. Ideas about sex and relationships begin to form in adolescence. It only makes sense, then, to begin conversations on this topic during this formative period in students’ lives.

A survey administered by the National Children’s Bureau in England asked 14 to 25-year-olds about their experiences with consent education. One third of students surveyed said they had not received any information regarding consent. Another survey conducted by the National Union of Students reported that 90 percent of high school students wanted sex and relationship education to be mandated in public schools.

Twenty-five states currently mandate sexual assault education in public schools, though the caliber of this education varies from state to state and school to school. There is currently no similar federal mandate.

While the increase in mandated education is forward momentum, it does not solve the problem. Girls and women are often educated on how to defend themselves against violence. It is crucial that women be cognizant of potential threats, but this approach fails to recognize the root cause of sexual violence in two ways. First, both men and women can be victims of assault, and teaching girls about defense forgets that boys are also often subject to sexual misconduct. Secondly, teaching girls to defend themselves against assault takes the stance that assault is inevitable. It fails to be proactive in the prevention of assault.

Students should know before they reach high school that any non-consensual sexual advance is wrong, regardless of the perceived severity of the advance.

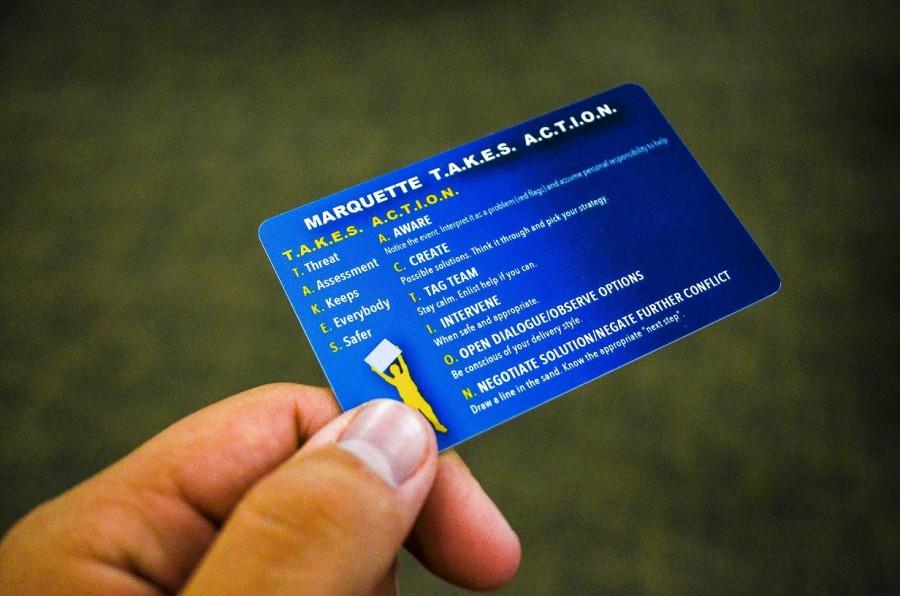

Sexual assault prevention should be discussed in conjunction with consent, and at a far earlier stage in students’ academic careers. These discussions need to happen at the middle and high school levels. Consent should be such a pillar of health education that by the time a student arrives on campus, they are fully equipped to intervene and educate others on the matter.

Fifty percent of all campus sexual assaults occur in the first four months of the academic year, according to RAINN. Making sure students have a basic understanding of sexual violence prior to arriving on campus is crucial in the prevention of assault.

This would not minimize the responsibility of universities to educate on these issues, but it would develop a foundational knowledge and facilitate further education on consent and assault prevention.