There is a new set of eyes on men’s soccer players this season, and it is not just coaches, scouts or supporters – it’s satellites.

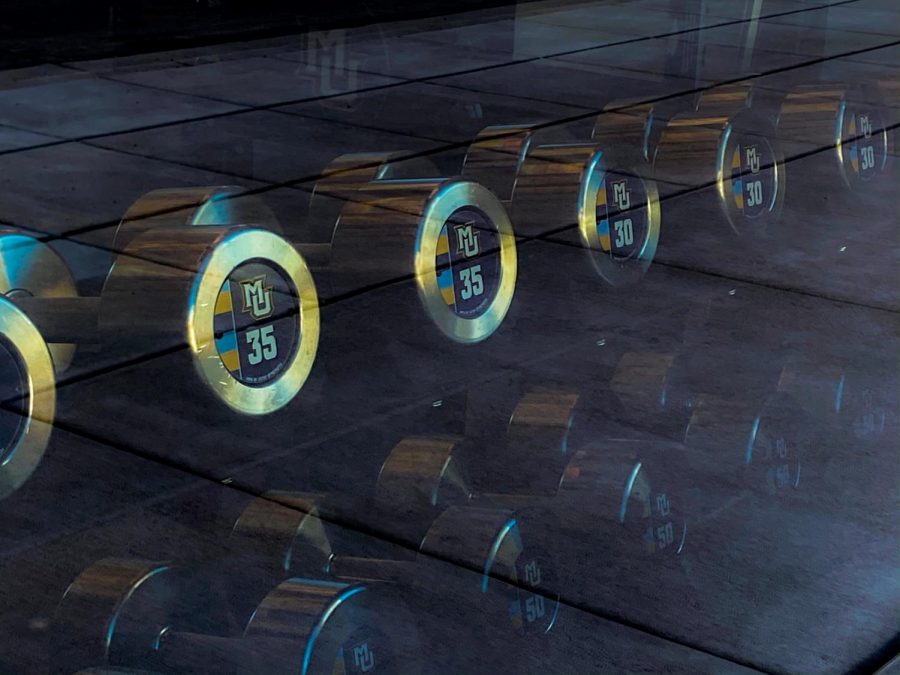

Marquette is using Catapult, a global positioning system monitoring device that measures various internal and external statistics, to help coaches understand how hard a player is working and how well they are standing up to the pace of a given practice or game.

Prozone and InStat are also analytical tools that help understand what worked and what went wrong during a particular game. It uses heat and pass maps, tracks players’ movements and precision, and gives coaches a comprehensive report on any player.

Head coach Louis Bennett believes in the long run, the technology can change the way that teams train.

“Back in my day, it used to be you trained 100 percent, 100 percent of the time and if you got hurt, you iced, strapped it and got on with it,” Bennett said. “Fast forward to today, we have the instruments to train smarter … Our hope is to be able to have a little more science behind the game and fuse it all together.”

The data is most helpful with health issues. Using a baseline at the beginning of the season, these tools can help coaches and medical staff understand how close or far away a player is from returning to injury, based on their start-of-season metrics.

Emily Jacobson, the program’s assistant strength and conditioning coach, monitors GPS data and analyzes the statistics such as monitoring heart rate and fitness, ensuring that each player gets the most out of practice.

“As a former player, I obviously knew what it was like to play,” Jacobson said. “When I started coaching, I all of a sudden wasn’t on the field, wasn’t going through what everyone else was going through, knowing that I’d been through similar things with the players. The data and the numbers for me, was a better way for me to understand what the players are going through on a daily basis.”

Jacobson, who graduated in 2013 and played on the women’s soccer team, started coaching and instantly embraced the data revolution. Jacobson realized the potential of statistics, so she and the rest of the Sports Performance team, along with the coaching staff, agreed to implement Catapult.

The GPS device is designed like a sports bra. Players wear it on their chest, and the monitor goes in-between their shoulder blades. Once the device is on, it tracks the player’s every movement and downloads the data to one of two storage systems. Open Field is a storing system that houses the data after the game. The other method is syncing the data to the Cloud, where Marquette’s Strength and Performance team and Catapult staff members analyze most of the data.

Thanks to Catapult, the Strength and Performance team analyzes rate of percieved exertion metrics, which measures intensity through internal and external factors. An internal load is a measurement in the body, such as heart rate. An external load is outside of the body, which includes metrics such as distance covered, how fast they run and how much force their bodies may be going through. Catapult is considered the gold standard in analyzing an external training load metric.

“We want their external outputs to be very high and their internal outputs to be relatively low,” Jacobson said. “That’s someone that is well adapted and is ready to the work that they are asked to do. That way we can see how much work a player put in.”

The program has used Catapult since August, and while Jacobson said they are still in the process of collecting data, which will continue into the spring season and next fall, the results have been telling.

“We will look at practice-by-practice and compare it to different weeks and games,” Jacobson said. “The possibilities are almost endless of what we can do with the data, and I think it will be really, really important to see how this Catapult piece fits in to the overall program plan.”

Despite the easily accessible statistics, Bennett believes that while numbers never lie, they must be integrated with a coaches’ intuition.

“Its told us something we’ve already known: that we’ve been in every game,” Bennett said. “You can’t just go off of the numbers; when you’re there in the game, you have to feel it. Like sometimes, we can make lots of passes, but we weren’t really in the moment. You can use the data and it certainly helps, but you have to use the eye-ball (test).”

While the numbers the account for plenty of data including players’ fitness, they can’t account for everything.

“The data is just to affirm what you see,” Bennett said. “We can’t have just science and numbers running soccer, because it doesn’t work like that. Soccer is a really passionate and emotional game. You can’t make up numbers for that.”

Jacobson joins Bennett’s coaching staff for meetings twice a week to dive into the numbers and see what they say about a game or practice. She also attends every practice to download and analyze the daily data.

Twelve players have worn the monitor this season, including midfielder Luka Prpa, who finds the data useful for his development on a game-to-game and practice-to-practice basis.

“I like to check out my workload to see if I am working hard enough or not, and it keeps both the team and the coaches all on the same page,” Prpa said. “I have not had any sort of technology and like this, and there’s certainly never been an emphasis on analytics before I got here, so I think it definitely helps a lot to give players a real sense of where they are at.”

While Marquette is still testing out the benefits of the wearable technology, one thing is clear: data analytics in soccer are here to stay.

“While the number’s aren’t everything, they are certainly a source of discussion,” Bennett said. “It’s fuel for the future, and I think that it will only help our sport grow, and players will only continue to develop and train smarter as a result of this.”