Students living in off-campus housing may be subject to service lines made of lead, which could potentially contaminate water used to drink, cook and bathe.

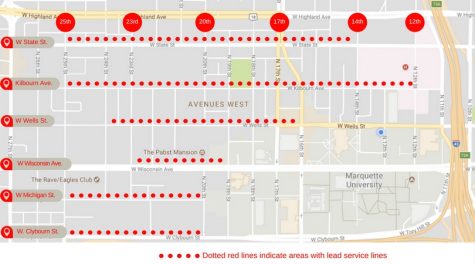

There are 123 properties with lead service lines located between 11th and 25th Streets and Clybourn and State Streets, where many students live. This number represents a fraction of the 70,000 lead service lines throughout the city.*

Many duplexes on 21st and Michigan Streets are among these 123 properties. Students who live in these homes do not make the call if the pipe needs to be replaced. Since the landlord owns the properties, he or she must be the one to replace it.

There are some discrepancies about whether the mere existence of a lead service line poses a hazard to the community. Some city officials and engineers say it does not, because the pipes have a coating that protects the water from lead contamination.

But several advocacy groups are wary of this conclusion.

“We are drinking water out of a lead straw,” Brenda Coley, co-executive director of the Milwaukee Water Commons, said. “We can’t predict how much and when the lead will leach into the water.”

Milwaukee water itself has no lead in it. The concern is the service lines. If they were somehow disrupted or moved, the lead could leach into the water supply, but the likelihood of that happening is unclear.

“You could test it 50 times and never get a defect and then on that 51st time maybe you get a flake,” Patrick McNamara, assistant professor and civil construction and environmental engineer, said.

McNamara said the coating is fairly effective.

“It would be rare to have lead in the water,” McNamara said. “We have pretty good control on our water quality.”

Although not everyone can agree on the imminence of the threat, there seems to be a general consensus that the service lines need to be replaced. The Milwaukee Water Works plans to replace over 600 lead service lines in 2017. There are about 380 completed and the rest are under contract.

Mayor Tom Barrett said the city’s goal for 2018 is to replace 800 service lines, when he proposed his budget to the common council. Coley fears this rate may not be fast enough.

“It’s not up to scale in any way or fashion,” Coley said, noting that the total number of lead service lines is upwards of 70,000.

“They are not handling the issue with the importance and urgency it calls for,” Coley said.

Public vs. Private

Part of the hold is a lack of funding. It’s difficult to establish a funding plan, because the service lines run past private owners’ property lines and into the public street.

Therefore, it is partially owned by the city and private property owners.

A proposal was introduced to the state legislature to increase the city’s water rates to help raise funds to replace more pipes. But it was struck down because public dollars from Milwaukee Water Works cannot be used to fund private repairs.

In emergency situations where there are leaks or lateral breaks, the city will pay for the public portion and subsidize the cost for the privately owned part of the service line.

Unless in the event of an emergency, much of the housing near campus will be unaffected by this initiative. Places such as daycares and schools will be a priority because they have vulnerable populations.

Lead exposure can cause damage to the brain and nervous system, behavioral problems, slowed growth and development according to the Center for Disease Control.

The current system addressing high-risk areas and emergency situations isn’t enough, Coley said. She added that all of the lead service lines need to be taken out.

“They need to come up with a systematic plan,” Coley said. “This can be done in a generation, so our children and young adults aren’t exposed to lead over time.”

But to work at a faster rate is not financially possible, according to Alderman Robert Bauman. There are about 74,000 service lines that need to be replaced costing about $6,000 apiece.

“That’s just not realistic,” Bauman said about removing all the service lines. “Someone would have to drop half a billion dollars on the city.”

If there was a decision made to replace all the laterals, half the cost would be covered by the taxpayers, Bauman said.

“It’s a convenient excuse to use the taxpayer as the problem,” Coley said.

She attributes much of the problem to a lack of awareness, adding that local government needs to do a better job of educating the public on this topic.

Many point to other initiatives the city has managed to fund.

“An example that people often give is we got together to fund a basketball stadium,” said David Strifling, director of water law and policy initiative and adjunct professor of law. “Why can’t we get a similar amount of money to do something about this problem?”

Close to Campus

Given the city’s aging infrastructure and water crises throughout the nation, Marquette partnered with an environmental engineering firm, Sigma Group Inc., to test the quality of the drinking water across campus in June.

Twenty-eight buildings were selected based on building ages, populations served and presumed drinking water consumption. Academic buildings, residence halls and university-owned apartments were some of the buildings included.

One drinking fountain in the administrative side of Straz Tower was identified as a concern, and was removed.

Many institutions and cities have become increasingly aware of water infrastructure after the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. However, water is not the sole culprit to lead contamination.

“I would say it’s interesting to note there have been some higher cases in Milwaukee area, but our lead in the water is not detectable, but we still have a concern about lead in blood levels,” McNamara said.

That means there are other sources of lead in Milwaukee area, McNamara said. He said that soil or dust in older residence areas are also points of concern.

“Part of my fear for the public … is we put all our time and resources into changing our distribution system and fix all the pipes, we could still have lead in other places,” McNamara said. “We didn’t even fix the main issue.”

Short-term Solutions

Strifling echoed the sentiment that Milwaukee’s water situation is not as dire as Flint’s.

“We’re not Flint because Milwaukee is doing more,” Strifling said. “You see Milwaukee doing some innovative things.”

Last year, the city partnered with A.O. Smith Corporation, a water heater manufacturing company, to provide free water filters. The city health department continues to provide them at a discounted rate.

Although filters will protect residents from lead contamination it is by no means a long-term answer, Strifling said.

“Milwaukee has to do more. Those pipes need to come out eventually,” Strifling said. “We just have to figure out a way to pay for that.”

Click here to see if your property is one of the areas effected.

*Editor’s note: The numbers used are courtesy of the city’s online database, which was collected in November 2016.