When Josefina Martinez was nine, her family applied for tourist visas to the United States. They came to Chicago from Guanajuato, Mexico, and 11 years later, their vacation has yet to end.

“The visa expired while we were here, and still today we are undocumented,” said Martinez, whose name was changed for anonymity purposes.

Now a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, Martinez has been living without fear of deportation due to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals executive order. But President Donald Trump announced his plan to repeal former Obama-era immigration policy Sept 5.

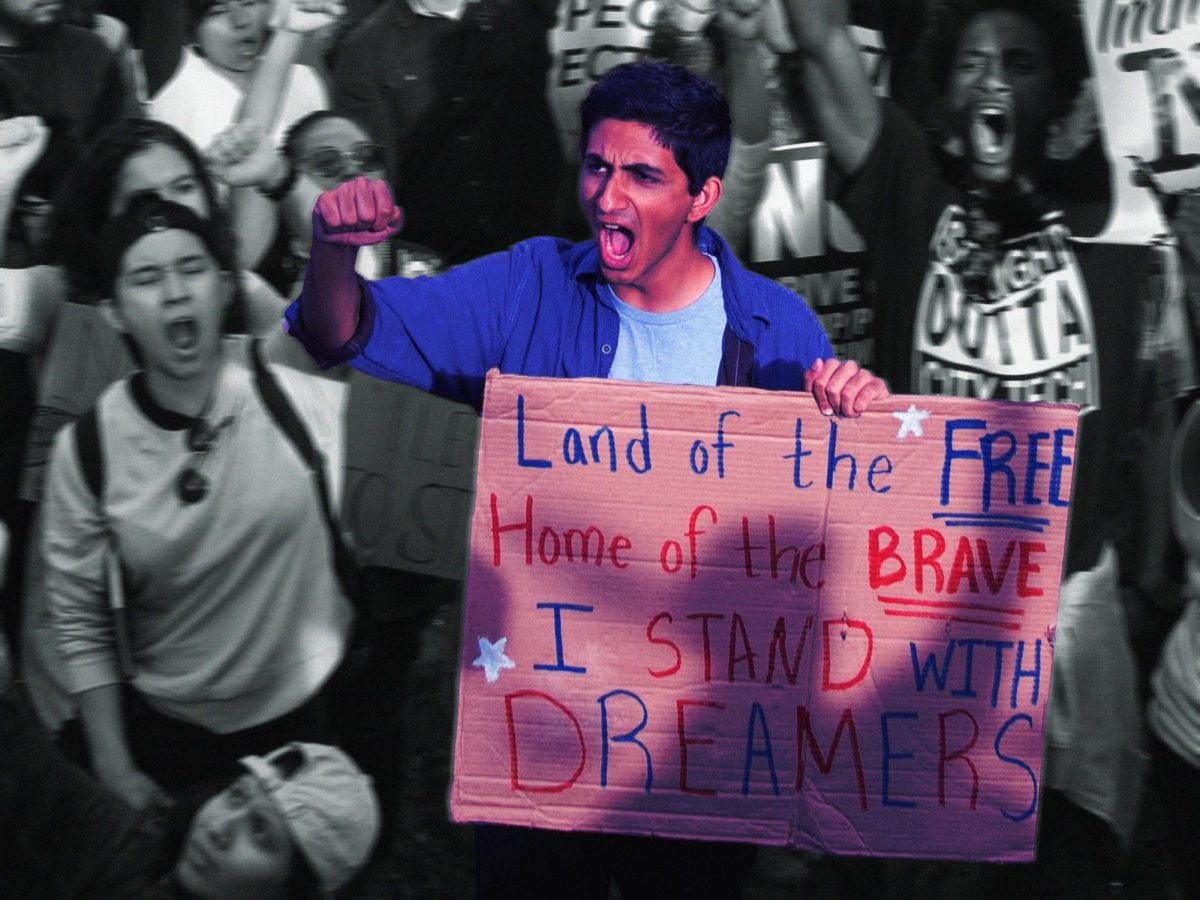

DACA provides relief for children who were under the age of 16 when they came to the U.S. illegally from fear of deportation. Removing DACA opens up the possibility of deportation as soon as next March.

If repealed, some 800,000 young people around the U.S. would be subjected to that possibility, many of them students. Marquette does not require disclosure of documentation status when applying, but the university has a good sense of how many undocumented students attend Marquette due to the responses received on applications, Jacqueline Black, associate director for Hispanic initiatives, said.

“People don’t realize that they’re in class with us every day, they pass us on campus, they live in dorms with us,” Martinez said in reference to the undocumented community on campus.

Growing up undocumented

Jonathan Irias vividly remembers crossing the Rio Grande at the age of six.

“The current almost swept me away … My father ended up using an inner tube and swimming back and forth across the river with one of us in it at a time,” Irias said.

His family rode a bus from Guatemala City all the way to the U.S. border, sleeping in bus stops along the way. For their first month in the U.S., his family was homeless while they saved up money to take a bus to Milwaukee.

Irias is now a freshman studying psychology. But the only legal citizen in his family is his younger sister, who was born in the U.S. Irias’ mother works as a janitor, and his father in the construction industry. His mother has a work permit, but his dad still technically doesn’t exist in this country.

“My parents didn’t come here for themselves, they came here for their children to have opportunities they wouldn’t have in Guatemala,” Irias said. “I didn’t want to leave Guatemala, it was a choice made for me by my parents … I wanted to stay with my grandmother.”

One large issue with deporting young people protected under DACA is that they grew up in the U.S. and are accustomed to the culture. “They don’t know anything else, they would be deported back to countries they don’t remember being in,” said Louise Cainkar, an immigration policy expert in the Social and Cultural Sciences department.

For students like Martinez, they feel a certain helplessness about gaining a permanent legal status.

“People who have lived here for basically their entire lives and who pay taxes, we can’t even vote,” Martinez said. “Politicians don’t favor undocumented people. That’s something you learn, and we can’t even vote for the politicians that might.”

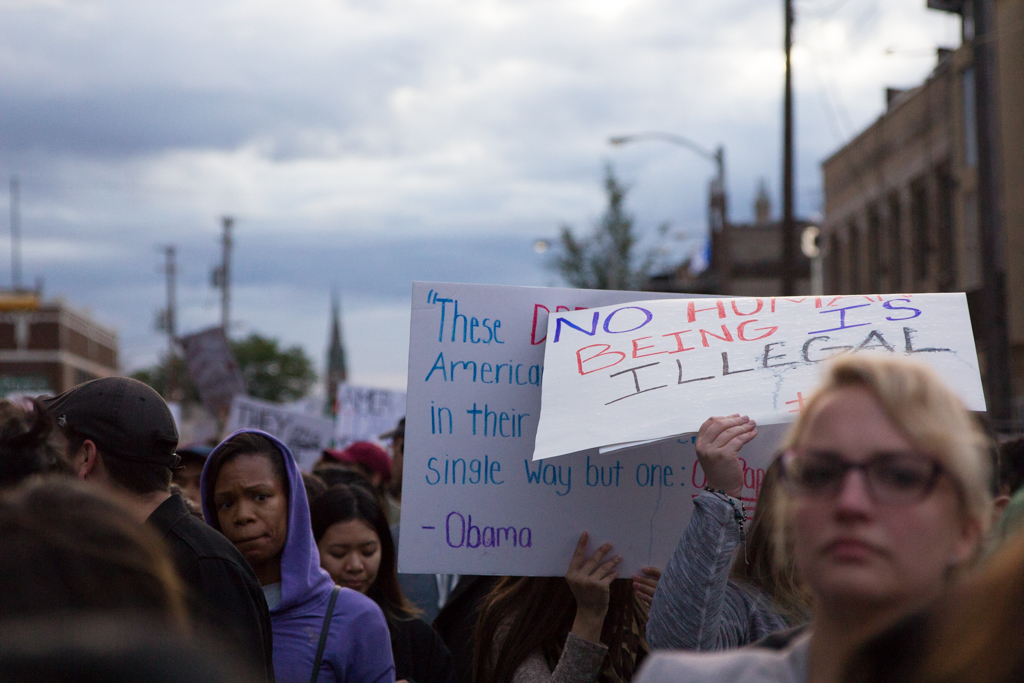

Trump’s repeal announcement has received backlash, with 58 percent of Americans support keeping DACA, according to a Politico poll.

Angel Fajardo is a junior studying secondary education whose father came to the U.S. during the Guatemalan civil war legally as a refugee, but that status eventually expired. His mother came illegally from Mexico, but Angel was born in the U.S. Today, neither of his parents are citizens, despite having lived and worked here for nearly 40 years.

After Trump announced his intentions to end DACA, Fajardo fears the buck won’t stop there and being born a citizen won’t protect him.

“I’m worried DACA will be just the first thing on the chopping block. (Trump) campaigned heavily on severe immigration policies, including things like birthright citizenship,” Fajardo said.

Fajardo said that almost every single student of Latin American descent he has met at Marquette has, to some extent, a similar story.

University response

The university has spoken out in support of undocumented students and their families.

“Consistent with our Catholic, Jesuit mission, we welcome all students to our campus. We’ve emphasized this welcoming message in numerous ways to start the school year making our stance clear, consistently calling for action from Congress to adopt a permanent solution to all of our students to achieve their dreams,” a university spokesman said in an email.

The university issued a statement in support of undocumented students Sept. 5, but declined to designate themselves as a sanctuary school, as other universities have.

“Rather than focusing on a general designation other schools have adopted, we’ve specifically and clearly outlined our Marquette University policies. You can find these policies as well as our university statements on our diversity website,” a university spokesman said.

The statement calls on congress to adopt a permanent solution that would allow all students to achieve their dreams.

“Marquette needs to keep student information confidential and offer financial aid if DACA was to go away,” Julia Paulk, director of the Latin American studies program, said. “Marquette is supposed to be committed to social justice … People who have grown up here should have the same opportunities as those born here.”

Students like Martinez and Irias have reason to fear they would not be able to complete their Marquette education if DACA were to be repealed.

“Immigration doesn’t care if I’m on a full scholarship,” Irias said.

When asked if he thinks the university is doing enough to protect students, Fajardo said he sees they are trying to navigate the political landscape. “It’s hard when the university takes any kind of stance, especially when they rely heavily on donors,” Fajardo said.

Rev. John Thiede, S.J. is a professor of Latin American theology and specializes in political theology. In his opinion, it is the responsibility of Jesuit institutions to provide resources and speak out against situations like a potential DACA repeal.

“Here at Marquette, if we actually want to ‘be the difference,’ we need to combine our pillars of faith and justice and see these people as human,” Thiede said. “Education is the great equalizer.”

Thiede takes issue with the idea of a human being considered illegal. “They are fleeing poverty for better lives … Jesus knows better than most what a true pilgrimage is, and I think he was walking with those parents when they came to this country,” he said.

Students like Martinez, Irias and Fajardo, along with their supporters from the university, want to see clearer legal paths developed for immigrants to gain citizenship.

Congress has six months to decide what to do about DACA, as it was never actually put into law during the Obama administration, but rather passed as an executive order.

Irias said he hopes those six months are productive. “I’m optimistic … I’m hoping that from this bad there comes a good,” Irias said. “Maybe out of this will come a solution. That is all I can hope and pray for.”