For book-lovers, spring break is the perfect time to cast aside readings for classes and finally start that book you’ve been meaning to read for months. For me, that book was “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City” by Matthew Desmond.

Desmond, a Harvard sociologist, has spent nearly a decade researching the relationship between poverty and eviction in Milwaukee. I was initially drawn to ‘Evicted’ because it tells the stories of families in Milwaukee struggling to keep a roof over their heads. It was eerie being able to recognize street names and Milwaukee landmarks mentioned throughout the book, and heartbreaking to hear the disparities present between the individuals’ renting experiences in Milwaukee and my own.

In 2008 and ’09, Desmond lived alongside these families, witnessing first-hand the systemic racism and housing discrimination that plagues these individuals, and the effects of the lack of consistent housing on their mental and physical well-being.

For example, among Milwaukee renters, over one in five black women report having been evicted, compared to one in 12 Hispanic women and one in 15 white women. This sobering finding was one of Desmond’s motivations behind this book. Many people are familiar with the fact Milwaukee is home to an area with the world’s highest incarceration rate for black males, however, what I was unaware of is that housing discrimination — especially eviction — is a serious issue for black women. As Desmond puts it, “Poor black men are locked up; poor black women are locked out.”

What surprised me even more than the statistics, though, was that I had been living on the same streets where Desmond came to these realizations, and for three years. It’s hard for us students sometimes to understand the problems that exist beyond our campus sidewalks.

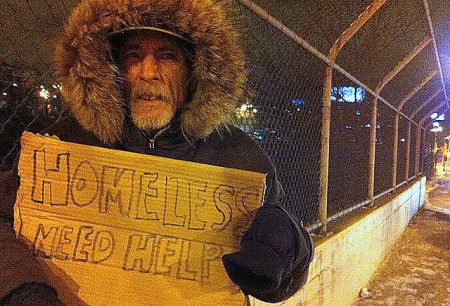

The stories ‘Evicted’ tells opened my eyes to this serious issue happening here in Milwaukee, but this book’s impact stretches far beyond our city. I learned just how far-reaching the affordable-housing crisis is in this country. Desmond urges his readers to recognize this vicious cycle and push for policy change to ensure affordable housing is a basic right for all Americans.

The most foreign perspective for me to understand throughout the book was that of the wealthy landlords in these impoverished areas. Being one of these Milwaukee landlords is actually extremely lucrative because when tenants can’t pay rent, they’re evicted, forced to pay the security deposit and the landlord can move on to the next family desperately seeking a place to stay.

With 20 percent of all renting families spending over half of their income on housing, the affordable housing crisis can no longer be ignored. Desmond argues, “public initiatives that provide low-income families decent housing are the most effective anti-poverty programs in the United States.” These initiatives, such as a more expansive housing voucher program and new policies set in place to protect impoverished tenants from being taking advantage of by landlords, would allow everyone the basic right of affordable housing that is reiterated by Desmond throughout this book.

As I read ‘Evicted,’ Desmond’s extensive fieldwork allowed me to step into the shoes of both the impoverished tenants and the wealthy landlords. He helped me recognize this harsh reality happening in Milwaukee and provoked within me not only a knowledge of the issue, but a desire for change.