It’s flu season, which means my coat pockets are lined with cough drop wrappers and my head hurts with congestion. In the past four days, I’ve been to Walmart three times in search of various cold remedy products, none of which have proven effective. My complexion is pale, and the skin below my eyes is a cartoonish mix of purple and blue. I’m sick, and you can tell.

Though uncomfortable, the visible symptoms provide a degree of leniency toward my obligations: a friend understands why I had to cancel lunch, a professor gives me an extra day to finish an assignment and my employer lets me punch out early.

Had the symptoms not been apparent, I doubt I would be afforded the same degree of leniency. Most of the time we know what sickness looks like, we know what health looks like and if we don’t exhibit symptoms consistent with the accepted picture of sickness, then we must not be sick at all.

This rationale can work for parents whose children are faking sick to get out of an algebra test, but for people experiencing symptoms consistent with mental illness, it’s isolating.

It’s rare that we notice when someone is struggling with mental health. Mental illness is glorified in popular culture, attributed to the manic pixie dream girl or the beatnik wannabe. Depression makes people complex, anxiety makes them exciting. What’s more though, the unglamorous pictures of mental illness we have are that of somebody either entirely unhinged or immobilized with depression.

But there isn’t a color-by-number picture of mental illness. Not all mental illnesses are the same, and the symptoms for each can look different on different people.

On some, depression looks like a loss of motivation or interest, while others handle depression by throwing themselves deeply into those interests. Anxiety can result in panic attacks but doesn’t always, and bipolar episodes can be especially difficult to notice because “moodiness” can result from things completely unrelated to mental health.

People struggling with mental illness aren’t treated with the same amount of empathy they would be if they were struggling with a physical illness, in part because nobody realizes they are struggling at all.

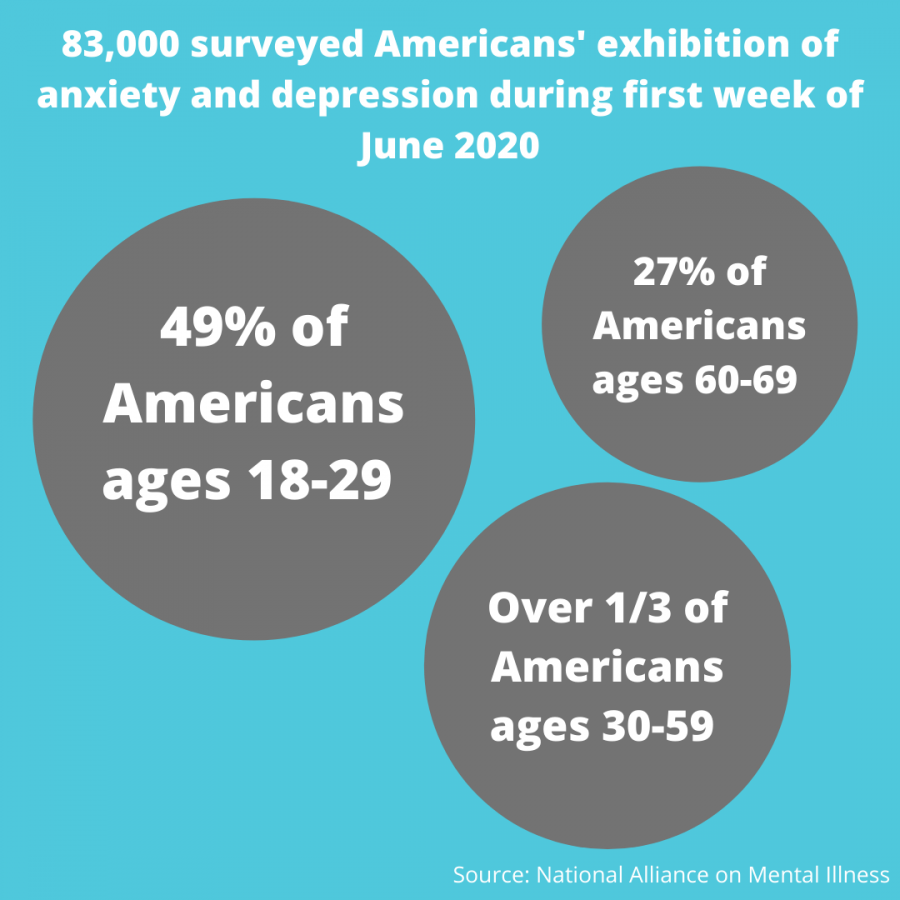

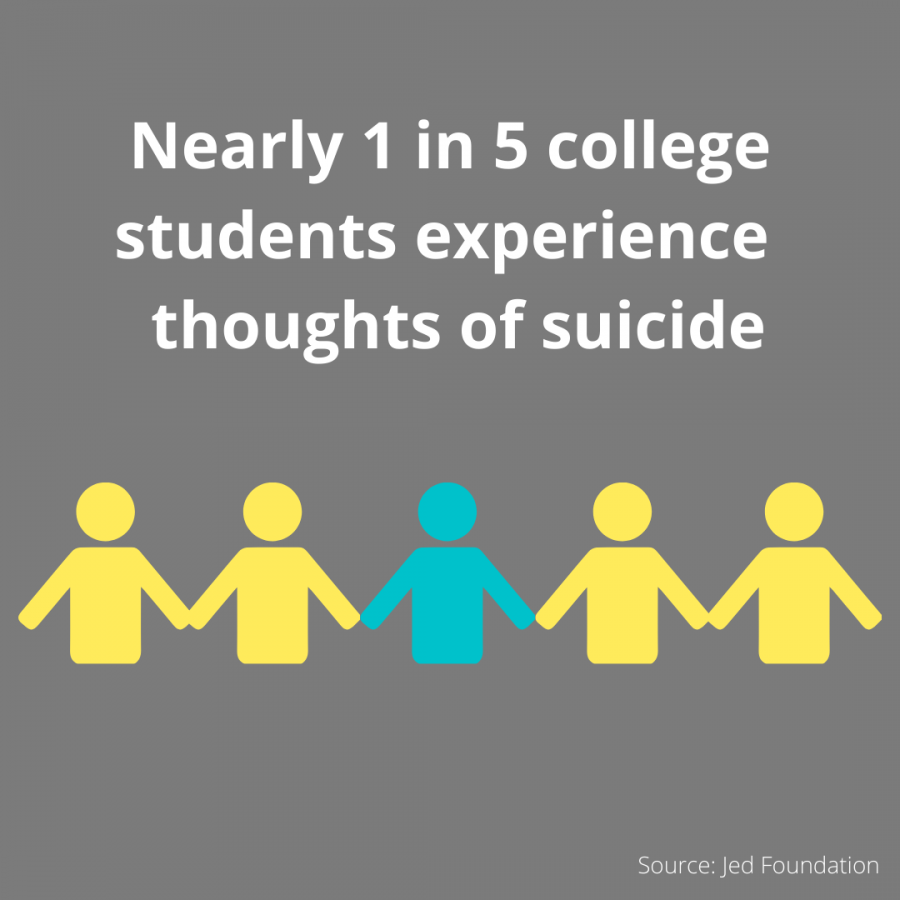

Is the problem a lack of proper education? Perhaps, but considering how one in five American adults will deal with some level of mental illness every year, it seems odd that our understanding of it would be so limited.

I think what’s really going on tells a much different story and has very little to do with education at all, but instead with acceptance. Society — American society especially — values those who can “pull themselves up by their bootstraps,” those who can power through the pain and overcome their obstacles without outside help. We value overwork, and we aspire to be as valued ourselves.

But because of those values, mental illness feels like something we ought to be ashamed of. It’s something for us to power through on our own. Under no circumstances should we bore our peers with our melodramatics and our mental woes.

We don’t notice when people are struggling because they hide their symptoms. We don’t have an accurate picture of mental illness because being candid about it means admitting weakness.

Sure, there needs to be better education and more accessible resources. But what we really need is to have a conversation about how to re-examine the implications of a value system that claims to empower us, but only tends to hold us down.