The 2016 Iowa Caucus has certainly garnered the media hype that it usually does. The Internet has been buzzing, not only about how close the results came in on the democratic side, but also with a number of newcomers raising the fair question, “why again do we do this?”

In the technology age, many question the seemingly antiquated caucus process and why it receives national attention. Although Iowa has held caucuses since becoming a state, they gained significance in the 1970s when Jimmy Carter focused his campaign efforts locally across Iowa and went on to win the nomination.

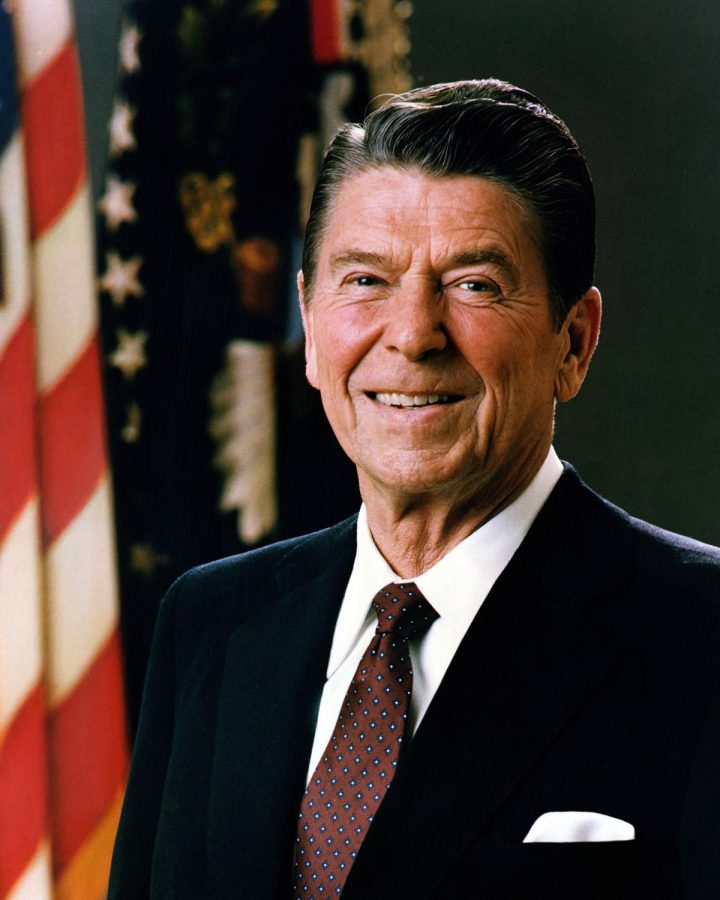

Still, the results are often inconclusive in terms of predicting the eventual nominee on the Republican side. Since 1980, only three Republican candidates who won Iowa went on to be the party’s nominee. In contrast, Iowa’s decision on the Democratic side has accurately predicted the party’s nominee all but twice since 1980.

This makes the tie in Iowa last week all the more unusual. Hillary Clinton was declared the winner, but Sanders fans don’t seem discouraged. And with a virtual 50-50 tie, they shouldn’t be. The Des Moines Register somewhat coolly announced that delegates are sometimes decided by a coin toss in the event of a tie. Some might say that decisions relating to the presidential nomination process are a tad more critical than who gets to kick first. Nevertheless, Clinton managed to beat insurmountable odds to win six coin tosses. Perhaps we should consider playing her Powerball numbers.

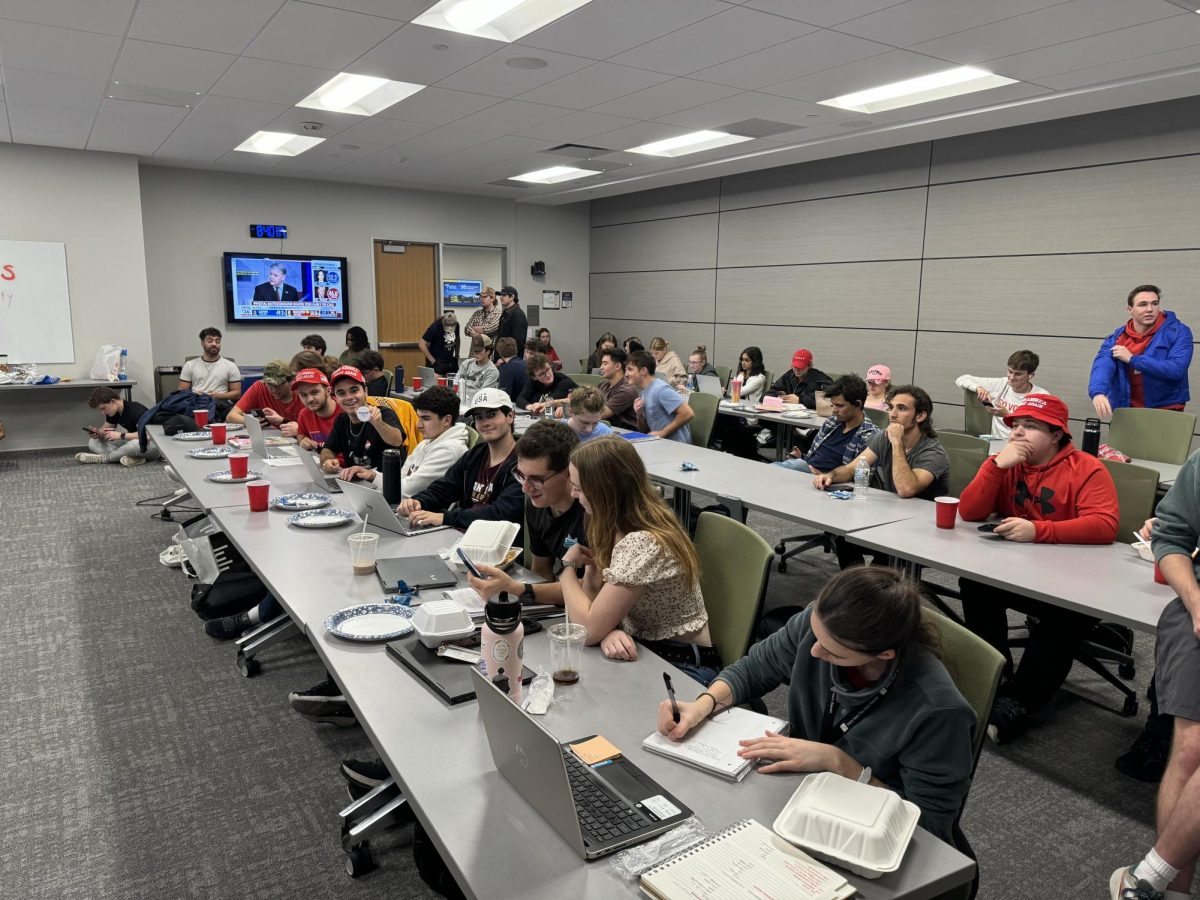

The Republican caucus in Iowa is pretty straightforward. The night begins at one of the 1,681 caucus sites where neighbors gather to discuss the issues and make cases for their favorite candidates. They eventually cast their vote by writing down their candidate and then tallying the candidates’ names. The Republican winner tends to be announced first.

The Democratic process is not as simple. With the attention it receives, it’s unlikely to change anytime soon. The night ends with the individual caucuses electing delegates to the county convention. The candidates are then assigned a state delegate equivalent. The state delegates will ultimately go on to represent Iowa at the party’s national convention in the summer.

Caucus-goers will choose a corner of a school gym, town hall or classroom to stand in, representing their candidate choice. Once the participants sort themselves, viability is determined. To remain a viable candidate in that particular caucus, candidates will usually have to meet a 15% threshold to stay in the game. If they don’t, participants are told to “realign” where they either recruit others to their group to become viable, join another group or go home. This was the point in which Martin O’Malley announced he was dropping out of the race, leaving his supporters to realign.

If the results are able to be converted evenly to a proportional amount of delegates, they are sent to the state party headquarters to be thrown in with the rest of the results. If not, it becomes pretty sticky. As we know, assigning the last delegates was a matter of mere decimal places, and evidently, coin tosses.

The caucuses primarily serve to determine a candidate’s chances of successfully moving forward, but not necessarily their strength vis-à-vis other candidates. To finish in the top four is not a death sentence. Anything below that, candidates drop out. It’s about time the GOP started to narrow a bit.

It’s not a perfect system, and Iowans seem to accept that. However, it’s a unique opportunity for everyday people to have their voices heard in the public arena and challenge each other face-to-face. It certainly inspires confidence in the political process when so many feel their vote matters little in an arguably convoluted campaign finance and electoral college system.

Still, Iowa is just the beginning of what seems to be an unpredictable race. The New Hampshire results have already dispelled any myths that one person or another has it in the bag. South Carolina and Nevada on deck.