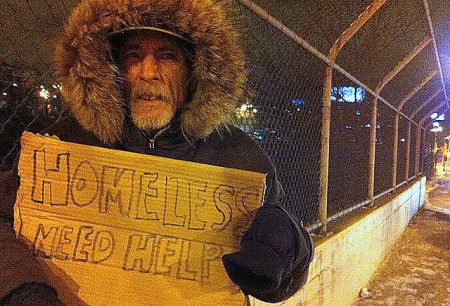

I could not believe my eyes. In the middle of our nation’s capital, amidst beautiful monuments and gorgeous government buildings, families were sleeping on the streets.

While attending the Les Aspin Center in Washington, D.C. last semester, I visited museums, gained professional experience and learned about policymaking. Despite these experiences, the pervasive issue of homelessness astounded me the most.

I was puzzled. How can the political hub of our nation, the city that represents freedom and opportunity for all, have such an issue with homelessness?

My curiosity continued in my Urban Issues class at the Aspin Center, where I started to investigate the problem. I made three observations: the first was the hard truth that homelessness was even more of an issue than I thought, the second was that much of the problem can be attributed to low hourly wages and the shortage of affordable housing, and lastly, that existing programs which could effectively end homelessness lack public attention and necessary funding.

To begin, homelessness and poverty are not unique to Washington, D.C. In Milwaukee, if you walk down to Lake Michigan at high noon any day of the week, you won’t get farther than two blocks before being asked for spare change.

Former CEO of Community Advocates Joe Volk said in an interview with James Causey from the Journal Sentinel that on any given day, around 1,500 homeless individuals can be counted in Milwaukee. In reality, this number is closer to 3,000, Volk said.

In D.C., though, the problem is even worse. According to an organization called Thrive DC, one-fifth of the city’s population lives in poverty, with 7,300 people homeless and 40 percent of those belonging to “families with small children.”

As I walked the streets of our capital city, these numbers became apparent. At night people slept under overpasses, in the courtyard of my internship building, and even in front of the Capitol.

Homelessness can be attributed to many things — unemployment, disadvantaged public education and disabilities, to name a few. However, low-wage jobs and the lack of affordable housing are the most pressing issues, especially in the District.

According to Linda Donaldson, an expert on homelessness in Washington and professor at the The Catholic University of America, the average individual should spend 30 percent of annual income on housing. In doing so, the person can afford other necessities such as education and food.

With the average rent at $2,026 per month, an individual making the minimum wage of $8.25 an hour in D.C. would have to work 157 hours per week, each week of the year, just to spend the expected 30 percent of income on housing.

This is a problem.

Many people you see sleeping on the street, whether in D.C., Milwaukee or any other city, have a job. They may catch the early bus to work in the morning but use backpacks as pillows in the park at night because they can’t afford rent.

James Causey noted in his article, “A developing crisis of homelessness,” that 20 percent of Milwaukee’s homeless are actually employed.

Before every business student in Straz Hall reports me to Fox News, I did take Intro to Economics my freshman year. I remember the chart that showed increasing minimum wage would create fewer jobs, cause more unemployment, and in turn, actually hurt the economy. However, I challenge you to tell a single mother working two jobs and still struggling to feed and house her children that raising her wage “will hurt the country in the long run.” An argument such as this does not register to someone who relies on shelters for a warm bed.

Still, raising wages and making housing more affordable will not fix the problem entirely. The continued funding of shelters and relief programs is also imperative.

One relief program we studied in D.C. is the Housing First model from Pathways to Housing. Getting away from the “prove yourself first” mentality, this program aims to meet people where they are in their lives and provide them with a safe and secure environment immediately. Only after housing is secured does the program address medical treatment, sobriety, mental health and employment.

A homeless individual suffering from addiction is more likely to beat that addiction if given the tools to do so. Providing patients with a place to live, Housing First allows an individual to get clean in a safe and comfortable environment. Other programs attempt to fix the problem by rewarding sobriety with housing. This is less effective because even when an addict is promised housing in the future, slipping back into addiction often becomes an easy fix to the horrible reality of sleeping on the street.

Housing First is a unique and abnormal approach, but one that has seen great success in cities like New York and D.C. This program gets people off the streets, and keeps them off.

Despite its proven worth, Pathways has headquarters in very few cities nationwide. Unfortunately, the program lacks both sufficient funding and widespread recognition.

These observations leave us with two underlying conclusions. First, the severity of homelessness in the U.S. must be made apparent, and educating those who are unaware must become a priority. Issues must be discussed and analyzed if we intend on fixing them.

Second, and most important, action must be taken. As Mother Theresa said, “Let us touch the poor according to the graces we have received, and let us not be slow or ashamed to do the humble work.”

In a country full of opportunity, there are still entire families sleeping on the streets of our capital. We can no longer be passive with the issue of homelessness. The discussion needs to change, and we must use new methods to fix this national crisis.