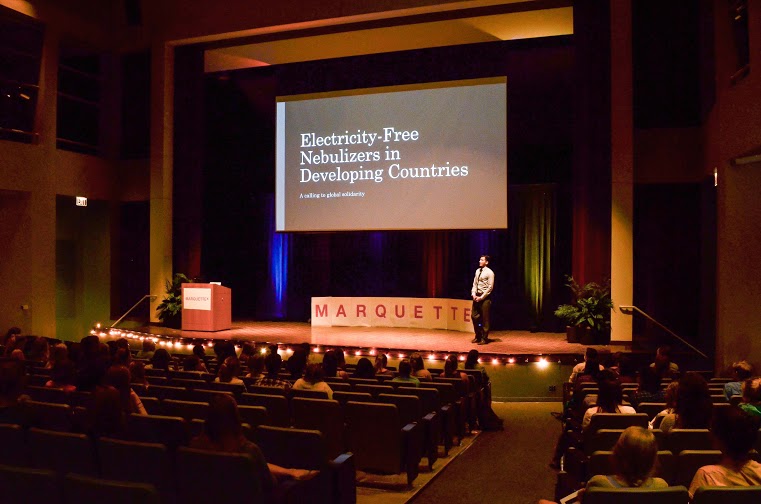

The College of Engineering is working to break cycles of disease and poverty one nebulizer at a time.

Lars Olson, interim chair of biomedical engineering, founded the human powered nebulizer (HPN) project around 2004 to serve people suffering from respiratory diseases in developing countries with limited access to electricity.

“Biomedical engineers make money making devices for people who can afford them,” Olson said. “At the same time, we should be making medical devices for people who can’t afford them.”

Since its start, the project has progressed from focus groups about the nebulizer’s design to field testing, clinical trials and a recent grant application to build an assembly facility in El Salvador.

Therese Lysaught, a former professor at Marquette, has visited El Salvador several times for the HPN project. She said the facility will be a resource if the nebulizer breaks and towns are too far from the local clinic or hospital. In addition, it will create jobs and contribute to the community’s overall development.

The HPN project is also a finalist for the Rolex Award for Enterprise. This award supports people who work on innovative projects that advance human knowledge or well-being.

Martin Rodriguez, a junior in the College of Engineering, got involved with the project after a presentation in his freshman-level biomedical engineering class. He said the nebulizer is a “single platform” in a larger effort to offset mortality rates in developing countries. Using human power to crank the liquid medicine into a mist, people can receive treatment for respiratory diseases like asthma, tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Lars added the HPN project is an example of what it means to be men and women for others.

“We want to make devices that help a huge number of people,” he said. “We really want to be walking and accompanying the poor.”

Lysaught said the project involves not only working with the poor, but letting them shape the whole project based on their needs.

“My favorite part about the project continues to be the amazing… enthusiasm and gratitude on the part of the people that we meet in El Salvador,” Lysaught said. “It overwhelms me.”

Rodriguez and three other students are planning a trip to Guatemala over winter or spring break to field test the nebulizer in a more rural area.

Lysaught said Guatemala does not have as strong of a medical infrastructure as El Salvador.

Rodriguez said he wanted to get involved with the project based on his upbringing in a rural town in Mexico.

“What I went through (in Mexico) I would consider as a privilege compared to what many people in Guatemala are going through and other countries of much lower income,” he said. “I feel entitled to give back.”

Rodriguez said the training is the biggest part of the project. It aims to enable rural towns in developing countries to be self-sustainable.

“The objective is you train one person from each village,” he said. “And then, that one person from each village is able to train their own villages.”

The model breaks down trust barriers between health care workers and local patients and provides immediate access to respiratory care at a low-cost. As a result, villagers become financially and socially responsible for the medical needs of others in their community.

The HPN’s motto is “to live and breathe for the poor.”

Lysaught said Olson has actively cultivated the project to identify with Jesuit culture.

“The ultimate goal is to put a million units in the hands of community health workers around the world and to make a serious dent in respiratory deaths,” Olson said.

AndrebMathrws • Dec 10, 2015 at 10:05 pm

May God Bless each and everyone of you. Your commitment and selfless acts of giving will be well rewarded. If there are ways I can assist, please share… Martin, I am proud of you. Stay the course…..

Fr. F. Melo • Oct 2, 2015 at 2:38 pm

“…a city becomes great when the righteous give it their blessings…” (Proverbs 11,11)