Lonny Sun smoked his first cigarette at the age of 12.

His parents were busy running a restaurant in Beijing, so Sun, a junior in the College of Business Administration, spent his time interacting with the kitchen staff. He said he started smoking because it seemed cool and because of the staff’s teasing and pressuring him to smoke.

Twelve years later, he’s still addicted.

“The question you should ask is ‘when do I not have this?’,” Sun said as he grasped his e-hookah, a $100 handheld vaporizer of pure nicotine.

According to health assessments conducted for Marquette’s Center from Health Education & Promotion, Marquette students are smoking less tobacco, indicating a 5.2 percent decrease from 2007 to 2012.

Still, changing opinions on tobacco in American culture are not representative of global attitudes, reflected in what is said to be a higher number of smokers in the international student population, although official data on tobacco use by Marquette’s international students is not available.

“In a social context, I think American teenagers tend to be social drinkers rather than social smokers,” said Cassidy Bannon, a sophomore in the College of Health Sciences. “I’ve noticed that international students smoke in groups, which further emphasizes the social aspect of it for them.”

Jeffrey Drope, associate professor of political science and director of the American Cancer Society’s Economic and Health Policy Research Program, works on an international level with governments on tobacco-related policies. He described the years of his own college days when people could even smoke in hospitals.

“I remember when I went to university in the late 1980s early 1990s,” Drope said. “You couldn’t smoke, but I remember my lecture hall still had cigarette ashtrays in each chair. And I remembered my professor saying that not too many years before, students would smoke during class.”

This is still a reality for many people around the world, including Sun’s countrymen. He said people can smoke in supermarkets and other public places and there is no enforced age limit for how early one can start. About 45 percent of Chinese men smoke and the country has one of the highest rates in the world.

“In Chinese smoking culture, when someone gives you a cig, and you deny it, it’s not appropriate,” Sun said. “But it’s getting more appropriate, because people think you’re a good person. The culture is changing.”

WORKING TOWARD CHANGE

Change began over 50 years ago when then Surgeon General Dr. Luther Terry, released the first Report on Smoking and Health in 1964. Many other organizations including the World Health Organization and the Center for Disease Control have educated people ever since. That is not an easy task when smoking has a deeply cultural role in other countries.

“I also feel that people have a very negative opinion here when it comes to people who do smoke,” said Constance Gavini, a junior in the College of Business Administration. She immediately noticed that people at Marquette do not smoke in public places as well.

Gavini, a French native, explained there are government action and education programs in France, including graphic warning labels on cigarette packages showing tumors and other health issues that can develop from smoking. Such labels are used in 60 countries, and were proposed but not implemented in the U.S. She also attributed changing French attitudes to teens seeing the side effects of smoking and an increase in cigarette prices.

“Smoking is extremely social in France, and in my opinion, this is the biggest difference between smoking in France and smoking in the U.S.,” Gavini said. “Teenagers start smoking because they think it is cool around 16, then people realize they are getting addicted to it and start stopping around 20. The 40-year-old generation smokes also a lot.”

This is what people like Drope and his colleagues are working to overcome by educating consumers, reforming policy and helping tobacco farmers grow other crops. He said the actions are taking hold.

“Things are changing quickly in (other countries) as well,” Drope said. “Beijing is going smoke-free in all public places this summer. It’s a really big deal, in fact a number of other Chinese cities are going smoke free as well. I think that if we had had this conversation 10 years ago, nobody would have ever believed that would happen.”

Marquette students like Sun and Gavini believe it is possible for their homelands to create a cultural change. They said Marquette’s smoking culture is vastly different than France or China’s and both believe that changes are being made, however slowly, to decrease the effects of smoking back home. Sun plans to quit smoking for good in the future and said he will not let his children smoke.

As for Marquette’s American smokers, though their smoking is perceived to be more infrequent, the risks are ever present. Drope worries that social smoking a few times a week can easily snowball into addiction. Health organizations remain in a difficult battle with tobacco companies to keep people from the bad habit.

“The tobacco industry had profits of over $44 billion in 2013,” he said. “Think about that. Think about the resources that are available in terms of their marketing.”

Anyway, he is optimistic.

“Everybody smoked when I was in college and I see much much less of it (in my students),” he said. “And lower, I think, even than I would have expected. Which impresses me. I think Marquette students are usually pretty smart, sensible young people.”

A SHIFTING CULTURE AT MARQUETTE

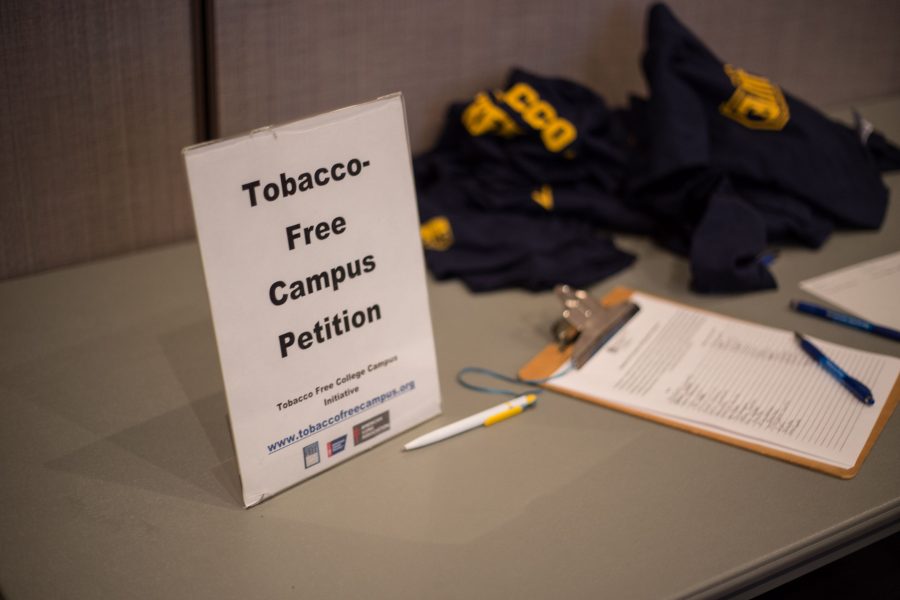

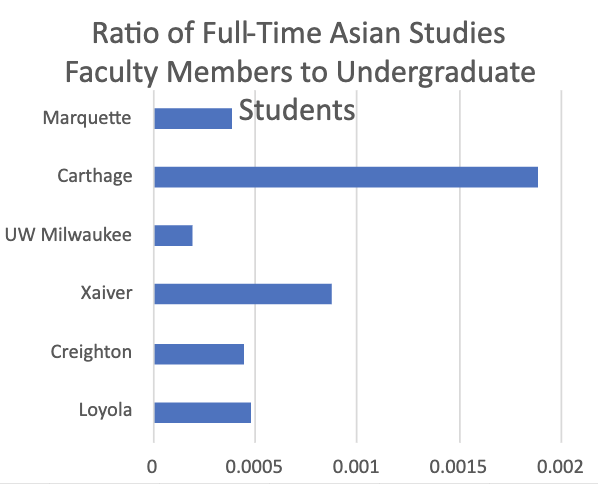

Like most campuses, Marquette has a dwindling number of students that consider themselves regular smokers: those who use cigarettes on a daily basis. Still, the university hasn’t taken the same steps others have to buck tobacco use.

More than 1,100 U.S. colleges are totally smoke free as of January 2015. This means students searching for a smoke must leave campus to do so. In Wisconsin this includes Alverno College, Milwaukee Area Technical College, University of Wisconsin-Stout and nearly a dozen others, but not Marquette.

Students are only allowed to smoke outdoors and at least 20 feet away from university-owned buildings.

The student’s daily indulgence was once a popular pastime for students everywhere. When Surgeon General Terry released his report about the negative side effects of smoking in 1964, 42 percent of adults in the United States were smokers. This number lowered to less than 25 percent in 1997, and finally down to just 18 percent today, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Although the rate of college-age smokers is decreasing, alternative smoking methods such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) are growing in popularity. While regular cigarettes burn tobacco, e-cigs run on battery power and generate nicotine, flavor and a cocktail of chemicals to the user while emitting an odorless vapor.

A starter kit can cost anywhere between $20 and $200, depending on the brand. Because of the limited research, the exact effects of e-cigs are still uncertain and the subject of widespread debate.

The devices are becoming increasingly popular among high school and college students. The 2013 National Tobacco Youth Survey found that in 2011 and 2012, 1.8 million middle and high school students tried the devices. Of these students, 160,000 had not smoked cigarettes prior to using e-cigs.

The study also discovered the percent of students who said they have used e-cig doubled in just twelve months, with 4.7 reporting usage in 2011 and 10 percent in 2012.

Connor Harold, a junior in the College of Communication, purchased his first e-cig last spring. He said he enjoys using the devices because they’re convenient and eliminate the three primary problems that accompany smoking cigarettes: the odor, the smoke and the waste. He started using cigarettes in high school and describes himself as a non-consistent smoker.

“E-cigarettes gave me the opportunity to not smoke cigarettes but still get that nicotine that I want–the action of sucking in through the cigarette without all the negative side effects,” he said. “But by no means is it a healthy alternative to smoking. I just kind of have this allusion that it’s better for me right now while I’m in college as a young adult.”

A PATH TO QUITTING?

Dave Dever, a sophomore in the College of Arts & Sciences, had his first cigarette when he got to college.

He said it started out as social smoking on weekends with his friends. Not long after starting to smoke, he purchased an e-cig, thinking it would be healthier to invest in one instead of cigarettes.

What started out as a weekend indulgence soon escalated into a full-blown addiction. He smoked his e-cig for over a year before he quit this January.

“At that point I was spending more money on it and I didn’t want to continue doing that,” Dever said. “I didn’t want to do something that was bad for me. I knew it was bad and I realized that I just needed to say, ‘I need to have the will power to stop.'”

Dever attributes his success in quitting largely to the fact that he had already made the switch to e-cigs. The liquid solution that is vaporized and breathed in by e-cig users can be purchased at different nicotine levels.

Dever began slowly lowering the percentage of nicotine he smoked over a few weeks until he was smoking a nicotine-free solution without dealing with withdrawal. Still, that was not the end of his habit.

“What I came to find out is that really, when you quit smoking, there are two kind of addictions that you’re breaking,” Dever said. “There’s the physical addiction to the nicotine, and then there’s the physical fixation. You learn to associate the physical act of smoking with stress relief.”

Quitting cigarettes is incredibly difficult in part because of the habit, or the motion itself, and also because nicotine is highly addictive. A study at Oregon Health and Science University has even found that it is as addictive as crack cocaine.

Dever said he believes that e-cigs are a chance that society must take advantage of as a possible route to quitting. He called for removing the stigma around e-cigs in public conversation.

“I think that’s the biggest issue, is that people want to make them into an enemy, they want to make them something to be afraid of,” he said. “They should be seen as A: a much healthier alternative, and B: if you so choose, a method to stop smoking.”

However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the CDC and world scientific community are wary of e-cigs overall. The FDA does not approve e-cigs as devices that can help stop a person from smoking.

They may have fewer harmful chemicals than other tobacco products, but they are not well researched or regulated, and still linked to adverse health issues. Worse, three in four e-cig users will also smoke cigarettes, according the CDC.

Dever still smokes cigars occasionally, but said he is under control and no longer addicted. He still remembers his addiction and what it was like to smoke but knows that it is bad for his health.

“I haven’t touched my e-cigarette or even had any liquid for it in two and a half months,” he said. “Honestly, it’s the kind of thing where now I don’t even think about it – it’s not something that I’m interested in.”