Choosing a college can sometimes be a whole lot like buying a house.

We look at price and location, we tour to see where we would sleep and eat, and in both cases, most people are willing to finance a huge heap of debt for an investment they can’t afford right away.

Both purchases are a big deal, but they both also come with a frightening level of uncertainty. We don’t tend to investigate the minutia of details that can affect prices, and we don’t exactly know what prices will look like in the years to come.

And prices in both housing and higher education have recently experienced surges with huge impacts on the general economy.

Now let’s pause.

Clearly we’re taking some freedom comparing two extremely complicated industries, but it illustrates the major blind spot consumers can have in terms of cost in complicated markets.

Wisconsin is now experiencing a public debate on what is driving those costs now that Gov. Scott Walker created plans to make $300 million in cuts to the University of Wisconsin System over the next two years.

Those cuts translate to a 13 percent cut to state aid funding, or a 2.5 percent cut overall (without taking into consideration restricted funds).

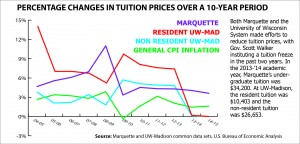

In exchange for the reduction, the governor proposed giving the system a lot more flexibility as its own public authority to restructure and cut costs. He also extended the system’s tuition freeze by two years and raised the prospect of mandating tuition rise at the rate of inflation for years after that.

Walker’s plan has attracted some fierce criticism from administrators in the UW System, who claim the cuts will result in layoffs and would threaten its mission. Walker’s office responded that the system should be able to cover some of the cuts with its unrestricted cash reserves. It also said the system can implement the cuts however it wants over the next two years (so not necessarily $150 million in cuts each year).

Leaders of the system’s statewide campuses reacted as any public bureaucracy would. UW-Madison Chancellor Rebecca Blank expressed concern in a statement that “large cuts have always been mitigated by additional tuition revenue from resident and non-resident students.”

Mark Mone, chancellor of the UW-Milwaukee campus, defended his school, calling it “one of the leanest and most efficient research universities in the country.”

Some UWM faculty members went so far as to sarcastically suggest cutting entire colleges to shore up the slashes.

It’s interesting to think how Marquette University President Michael Lovell would have responded to the proposal had he not left his chancellor post at UWM for Marquette last spring. In making the cross-town trip, he effectively took a position with a lot more budgetary flexibility to balance the books.

But make no mistake. Despite Marquette’s annual 3-percent increase in tuition, Lovell and his administrative team will continue to seek austerity strategies at Marquette.

Why? Because the university simply can’t keep growing the way it has been without impacting the families of students paying the tuition bills.

After tuition prices surged throughout the past decade, Marquette has expressly made an effort to keep costs down. The school made total budget reductions of $8 million in the current fiscal year, following up $2 million in cuts the year before. To put that into context, Marquette’s total revenues and expenses are expected to balance around $400 million.

The reductions included a major restructuring of top administrative offices and layoffs last spring. Marquette laid off 25 people in the spring and said another 80 positions were expected to be absorbed through retirements or not filling open positions.

And it’s not just Marquette. This is something that’s been happening across the country, at public and private schools alike.

So why, then, should we not expect it to happen in the UW System?

Yes, budget cuts are unpopular and never easy. And yes, they are certainly more difficult to make without a rise in tuition. We’ve certainly seen enough rhetoric on these points already.

But there’s another side of this debate that seems to be lacking: What should our society expect from our public university system?

The cost of higher education has not exploded because greedy college administrators are trying to take money from students. It’s exploded because there has been a demand for more non-academic services on our campuses — safety, IT, career counseling, on campus living amenities and diversity services to name a few, bringing us back to the consumer blind spot.

Just as people neglected to look at the details that led up to the housing crash, people generally do not look at the operating budget of universities while touring prospective campuses. They don’t look at administrative growth, or fiscal health, or even projected tuition prices in years to come. More often you’ll hear somebody say it’s about following that “gut reaction.”

To make matters worse, there’s a major distortion in what tuition actually means since very few people actually end up paying the sticker price. Most of us have some type of government subsidy on our hands too.

Here’s the kicker. Studies show that higher prices don’t actually have a negative affect on enrollment. In the meantime, student debt is piling up on the general public at unprecedented rates and is expected to severely limit our access to capital.

In a knowledge-based economy, that could be a big deal.

The governor may not have intended it, but his proposal could force Wisconsin to ask a question it’s been neglecting for some time — the same question people paying the bills to attend Marquette really don’t have the platform to ask.

How should our colleges be operated? What do we actually want to pay for?

We’ll just have to see if this conversation actually catches on.

Rob Gebelhoff is projects editor for Marquette Wire and a senior studying journalism and political science.