History professor John Krugler, 74, has been working at Marquette since 1969. This is his final semester.

Krugler spent the last 46 years moving up the academic ranks until he became a full professor in 2007, but at the end of this semester, he is becoming a professor emeritus, a rank awarded to qualified professors upon retirement.

“If I wanted to get my full salary as a tenure buy out, I would’ve stopped at 65,” Krugler said. “Obviously I stayed on for nine more years. I did this not because I needed the money, but because I wanted to be here, and I still felt I had something to offer.”

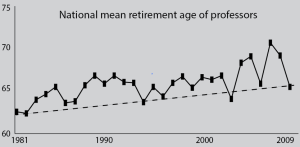

Krugler’s story of teaching beyond the standard retirement age of 65 is becoming more common on university campuses, and higher education studies show the trend has contributed to the rise in tuition prices.

Over the past three years, Marquette’s average retirement age of tenured faculty sat at 67, according to data from the Office of Institutional Research and Analysis.

Nationally, a study conducted by Fidelity Investments shows 74 percent of higher education faculty plan to delay retirement or never retire at all.

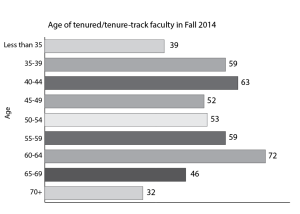

THE IMPACT OF AN AGING FACULTY

Joseph Daniels, chair of the Department of Economics, said the increasing age of faculty can be traced to a number of reasons.

“For an extended period we had lackluster returns in the stock market and very low interest rates that negatively impacted retirement accounts,” Daniels said in an email. Daniels added that uncertainty over health care insurance plans may have created situations where “there is a reluctance to retire.”

He also said that teaching is not a physically demanding job, which allows professors to remain active for longer. Compared to some jobs which require heavy lifting, long hours or a lot of travel, most professors are able to live a relatively relaxed life.

“If I was doing a 9-to-5 job, I would have been gone a long time ago,” Krugler said. “This is an ideal situation.”

But having older faculty may also have an impact on tuition prices. The Davis Educational Foundation conducted a study on the increasing cost of higher education, and listed the increasing average retirement age as one of the reasons.

“As the market stabilizes, faculty may return to retiring at a younger age,” the study said. “This would free up space for promising younger faculty and reduce costs.”

Economists put salary gaps between older and newer employees in terms of “compression” and “inversion.”

Salary compression happens when people are paid similarly, although they have different experience or qualifications. An example would be if a new faculty member was granted — or negotiated— a salary that is comparable to that of more experienced faculty.

Inversion, on the other hand, is when a new faculty member lands a higher salary than more senior faculty.

“The gap between new faculty and older faculty tends to be quite small (compression) and it is not uncommon for new faculty to come in at a higher pay level (inversion),” Daniels said.

This phenomenon is well-known for business faculty, Daniels said.

“Nonetheless, in just about any profession, someone who has been on the job longer and is productive will receive a pay raise that compounds over time,” Daniels said.

An aging faculty may also result in a generation gap between teachers and students. Tracey Sturgal, an instructor in the College of Communication who teaches a course on cross-generational communication, said age is a factor that can determine the effectiveness of an educator.

“Some people are better at recognizing that they need to connect with people through their language,” Sturgal said. “We like it when people talk the way we do.”

She also said effective teachers are able to adjust their communication when they recognize it is no longer clear. This is something Krugler said he and other professors “worth their salt” must do.

“Let’s face it, I recognize that when I make an allusion to something, students don’t always know what I’m talking about,” Krugler said. “That’s part of what makes this exciting is I’m still constantly working with 19- and 20-year-old students.”

University spokesperson Brian Dorrington said Marquette launched a phased retirement program in the 2012-’13 school year. The three-year program allows eligible faculty members to become part-time and receive 50 percent of their full-time salary, as well as a $14,400 supplement.

Part-time faculty must have a workload of at least six credit hours during both the fall and spring semesters to qualify for phased retirement benefits.

“A few faculty are currently taking advantage of the phased retirement opportunity and the university has had participants in the new program since its inception,” Dorrington said.

MAKING THE DECISION TO RETIRE

Krugler said the catalyst to leave Marquette was a partial-retirement offer made several years ago, allowing him to adjust gently to a lighter class schedule. Originally, he said he never intended to retire, but reconsidered that decision.

“As I’ve began to see the signs of aging, being in the classroom just took more and more energy,” Krugler said. “I didn’t want to be one of those people that someone had to come and take aside and say ‘Maybe it’s time you leave,’ so I thought I’d leave when I’m still ahead of the game.”

Krugler said faculty need to recognize their own limitations, and realize all good things come to an end.

Some students may hesitate to take classes with older professors, but Sturgal advises both students and professors should be authentic so they can reach a mutual understanding.

“I think trusting that everyone can learn from everyone regardless from where they are in their communication is key,” Sturgal said.

Alexa Decker, a freshman in the College of Arts & Sciences, said she does not believe in a mandatory retirement age. Instead, she said professors should realize when they are no longer good teachers and should take it upon themselves to retire.

“I think when you lose the ability to control the classroom and teach students is the correct time to retire,” Decker said. “If all he’s talking about is stories and not teaching, students have to learn on their own.”

For Krugler, the choice to retire was not a difficult one, aided in part by his wife’s desire to travel.

“She’s been pushing me to retire for some time,” Krugler said. “And I’ve resisted.”

For the time being, Krugler and his family will enjoy their travels to Amsterdam, Berlin and Ireland. Krugler also plans on finishing and publishing a book, which he will do under his new professor emeritus title.

Krugler said he will miss contact with his students and colleagues, and the refurbished Sensenbrenner Hall.

“People (teaching) history, we really tend to stick around,” Krugler said. “We love what we’re doing.”