For Reema Patel, choosing a career path after graduating from Marquette’s dental school will be all about helping people.

That’s an easy path to find in Wisconsin, which for years has had a persistent problem of low-income populations, many of them rural, with limited access to dental care.

“I don’t think I’d want to spend the rest of my life in a rural area,” Patel said. “But I’m young — I’m going to graduate at 25 — and it’s just so easy to take two or three years of my life and work in a rural area for people who can’t afford dental care.”

But a job like that also comes with challenges.

Working in clinics for these populations means providing care to patients who have no experience visiting dentists or little knowledge about dental hygiene.

“I’ll be honest, if you see these kids and the amount of decay in their mouths — it’s just terrible,” said Dr. Paul Levine, president-elect of the Wisconsin Dental Association.

Levine also recognized that the biggest obstacle to providing dental care for these populations is the cost.

Students who plan on serving these populations will have to rely on payments from limited state and federal government aid programs. That includes Medicaid, which can be used once yearly for cleanings and for some types of X-rays, and Wisconsin’s BadgerCare Plus.

Because these programs usually do not cover dentists’ costs, clinics often do not accept or limit the number of public aid patients.

On top of these difficulties, it is also difficult for students to commit to a career in the heart of central Wisconsin.

“You have no idea how much stuff could change in my life within four years,” said Abbey Christopherson, a first-year dental student. “Honest to God, I grew up in Milwaukee. I love volunteering, going for the weekend and serving everybody, but I’d prefer to be around my family in a more city environment.”

AN HOLE IN THE SUPPLY

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) identified 41 low-income population groups experiencing a shortage of dental care in Wisconsin, extending to more than 790,000 people.

In addition to wide expanses of rural areas in central and northern Wisconsin, concentrated shortfalls are located in urban areas like Milwaukee, Madison and Green Bay.

Overall, to eliminate the statewide shortage, the HHS estimated that Wisconsin needs to add 123 dentists to its workforce.

Marquette, which houses the only dental school in Wisconsin, is the main source of dental practitioners in the state, graduating 100 students a year. That number recently increased from 80 students during an expansion of the dental program in 2013.

Most of those graduates remain in Wisconsin, too, with about 30 percent leaving for careers outside the state.

While dental care shortages have persisted for years, William Lobb, dean of Marquette’s School of Dentistry, said he thinks his school will be able to graduate enough dentists to fill the demand in the state.

“It’s not really a shortage,” Lobb said. “It’s a maldistribution.”

Marquette does provide a fellowship program for students to work with rural areas in affiliated clinics in Appleton, Stevens Point and Eau Claire, giving prospective dentists the chance to work with patient populations they would not have considered otherwise. Lobb estimated these clinics to also provide dental care to people from each of Wisconsin’s 72 counties each year.

Still, Lobb stressed it is difficult to commit to these careers. Students may change their career path based on changes in their personal life, like getting married or desire to move to another part of the country.

“They get the opportunities when they’re here,” he said. “But we can’t tell them where to go.”

The Marquette School of Dentistry is working to add a rural track to its curriculum to help prepare students to enter their profession in areas in the state that need dental care the most.

The track would complement the fellowship program and would prepare students to enter one-person shops offering care for both emergency and regular dental needs. Still, implementing that track will require extra investment and time.

AN ABANDONED PLAN

Marquette has not been the only group trying to address the state’s shortages. The Marshfield Clinic, a health care system covering northern, central and western Wisconsin, also pursued developing a dental school that would specifically train dentists to provide care to needy populations.

The Marshfield Clinic abandoned those plans earlier this summer, giving up a $10 million grant it received from the state four year earlier.

A spokesman for the Marshfield Clinic did not respond to requests for comment, but Brian Ewert, the executive director of the health care system, told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that the decision was made based on whether it was a prudent use of Wisconsin’s dental resources.

The Marshfield Clinic secured the $10 million as a matching grant from the State Building Commission in 2010. Another $10 million came from Security Health Plan of Wisconsin, a nonprofit health insurance company.

The project would have developed a new rural dental education program, aimed at providing care to people who were uninsured, the Journal Sentinel reported.

But that plan attracted heavy opposition. Although the State Assembly passed the funding 61-35 in 2010, legislators who voted against — mostly Democrats — argued a better use of the money would be to raise fees paid by state health programs to dentists.

A few Republicans joined the dissent. Rep. Phil Montgomery (R-Ashwaubenon) said he did not think low-income residents in his district near inner city Green Bay would travel to central Wisconsin for dental care, calling the project, “a big white elephant.”

Peers in the dental trade, including Marquette and the Wisconsin Dental Association, voiced their opposition to the plan early on.

“We contended from the beginning that there wasn’t a need for two dental schools in the state,” Lobb said. “We probably would have been producing more dentists than we need.”

Lobb also said it would have required more resources for infrastructure and would pull away faculty from Marquette.

The new school would have put Marquette in direct competition with the Marshfield Clinic for more than $3.5 million in annual funding it receives from the state.

The School of Dentistry has been supported by the state since 1973 through in-state tuition subsidies and clinical operation support. When Marquette opened up the facilities it uses on Wisconsin Avenue, the state picked up half the cost at $15 million.

Both Levine and Lobb said they did not think the Marshfield Clinic’s decision to not open another school would not affect the number of dentists entering Wisconsin.

‘I’M LOSING MONEY’

Levine stressed the issue facing Wisconsin’s dental industry is not just getting dentists into the right areas offering care. It’s also about expanding funds to make it easier for dentists to offer care to public aid patients.

The state reimburses only about 30 to 35 cents for every $1 of services provided by private dental practices, and that doesn’t include the dentists’ salaries, according to the Wisconsin Dental Association.

“I’m losing money when I see patients from the state,” Levine said.

Part of the problem, he argued, is that public aid patients cancel or do not show up to appointments far more often than other patients, leaving unproductive gaps in his work day for him and his staff.

Part of the problem, he argued, is that public aid patients cancel or do not show up to appointments far more often than other patients, leaving unproductive gaps in his work day for him and his staff.

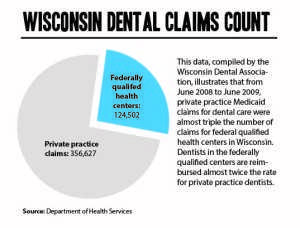

A few dental service providers, called federally qualified health centers, are reimbursed at almost double the rate of payment than private practitioners, but those do not cover nearly as many dental care claims as do private clinics.

“If they did that in certain areas with shortages, they could make a difference,” Levine said.

He also suggested the state could develop education programs to teach parents how to take care of their kids’ teeth or offer loan forgiveness to students who decide to provide care to the shortage areas.