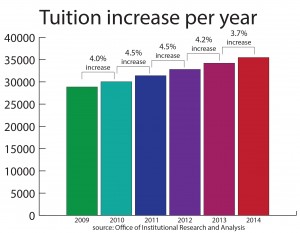

When I started college in the fall of 2011, the cost of a year at Marquette was about $42,000. In the three years I have been here, that price tag has risen nearly 12 percent, twice the rate of inflation, to $46,930. And this is not just a phenomenon here at Marquette. Across the country, colleges, both public and private, are raising their tuitions and charging more for housing and fees. As an example of how rapidly the cost of higher education has risen in the past 25 years, look at my father’s alma mater, Boston University. In 1979, my father paid $4,720 to attend the school, which, when adjusted for inflation, comes out to about $15,489.53. The actual price to attend that same university today, without even factoring in other costs such as housing, is $45,686.

When I started college in the fall of 2011, the cost of a year at Marquette was about $42,000. In the three years I have been here, that price tag has risen nearly 12 percent, twice the rate of inflation, to $46,930. And this is not just a phenomenon here at Marquette. Across the country, colleges, both public and private, are raising their tuitions and charging more for housing and fees. As an example of how rapidly the cost of higher education has risen in the past 25 years, look at my father’s alma mater, Boston University. In 1979, my father paid $4,720 to attend the school, which, when adjusted for inflation, comes out to about $15,489.53. The actual price to attend that same university today, without even factoring in other costs such as housing, is $45,686.

It is a fact that universities are spending more each year, requiring tuition to rise in tandem. For the 2011-2012 academic year, not-for-profit private schools spent more than $13,400 more per student than they did 10 years prior, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Costs are rising due to increased demand and expectations. According to the latest NCSE statistics, in 2012, 42 percent of Americans ages 18-24 were enrolled in some form of post-secondary education with 28.3 percent enrolled in a four-year college. When my father went to school in 1979, those numbers were 25 percent and 18.7 percent, respectively. And with easy-to-access loans from both the federal government and private lenders, more young people can go to college without having to deal with huge costs upfront.

Attending college in this country is no longer just about education. Students come to campus in the fall seeking an “experience,” and universities have been more than happy to accommodate. Comfy dorms, better food and nicer places to work out are all things students demand from their schools, and the cost of maintaining those amenities continues long after they are initially built. Programs and offices to manage all aspects of student life outside of the classroom, from fraternities to fitness, now cater to almost anything students desire. And with those new programs comes a new bureaucracy and its cost. Between 1993 and 2011, Marquette added 450 new full time non-instructional positions, with the ratio of students to administrators rising from 119 staff per every 1,000 students in 1995 to 145 in 2011.

We live in a culture that glorifies higher education for reasons outside of its original purpose. Our society views college as a means to get a well-paying job, as a rite of passage to adulthood and a way to gain respect and connections. In the American narrative, college is seen as a stage of life equivalent to childhood and old age, despite the presence of numerous alternatives that may suit students better than a four-year institution.

Now while a well-educated populace is a good thing, a piece of paper does not necessarily confer knowledge, nor does it guarantee success in life. People should have the ability to attend higher education, and preferably the ability to do so affordably. But societal pressure to attend, combined with unsustainable growth in the education sector, is creating a generation of Americans bound to billions in debt.

And so ask yourself this, why did you come to college? Because in the end, you get what you pay for.