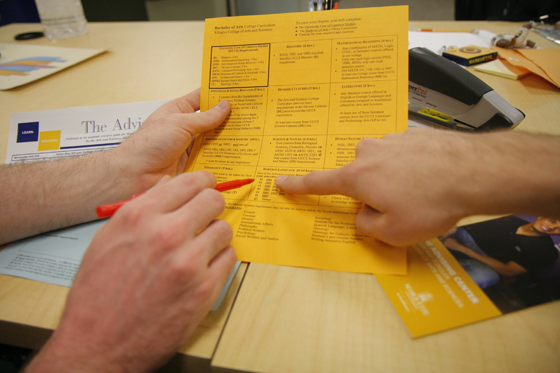

Monday marks the beginning of “Advising Week,” a week during which all students are supposed to meet with their advisers to discuss their schedules for the following semester, yet many do not.

Advising reform is not a new topic on Marquette’s campus. Marquette Student Government President Sam Schultz campaigned for reform, as has Richard Holz, dean of the College of Arts & Sciences.

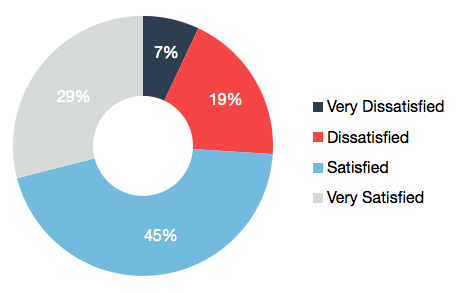

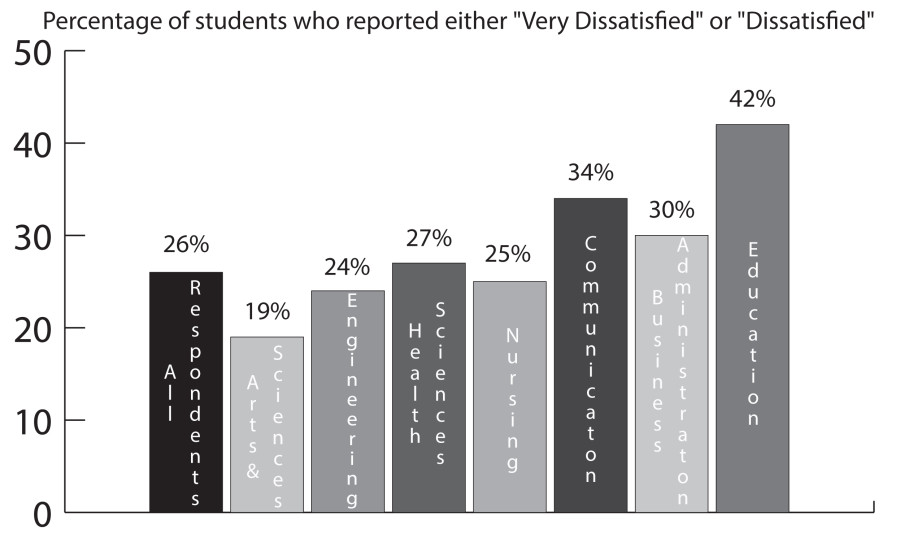

Yet, the problem persists. According to a 2011 Marquette Student Government survey, nearly one in five students in the College of Arts & Sciences were dissatisfied with their advising experiences, and the College of Arts & Sciences had the highest approval rating in the university at 80 percent. The College of Communication and the College of Education had approval ratings of 66 percent and 58 percent, respectively. The university as a whole maintains an advising approval rate of 74 percent.

More than one in four students is dissatisfied with their advising experience and nothing has yet been done to fix the problem.

One glaring example of bad advising is the case of Patrick Manner, a 44-year-old undergraduate student who decided to come to Marquette last year to complete his undergraduate degree. Manner said he hoped to enter Marquette’s Physician’s Assistant graduate program and was assigned an adviser in the College of Health Sciences.

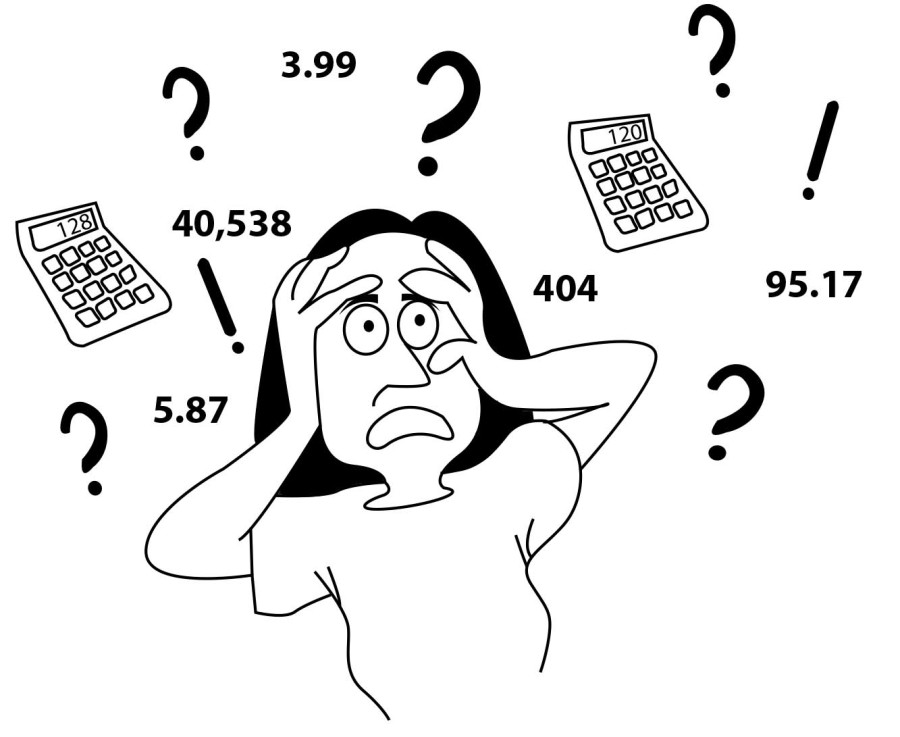

Manner said his adviser told him he would be able to apply to the PA program with the GPA he accumulated during his time at Marquette. When he applied, he said he was told that his cumulative GPA would include the GPA from his previous undergraduate experience from 25 years ago, making both his GPA too low and him ineligible to apply for graduate school.

Manner said he was told he would be required to take at least 70 credit hours — or two more years — to raise his GPA high enough to be eligible for the PA program.

“Not being able to apply is costing me two additional years of my life, if I pursue this,” Manner said. “It’s two additional years that I won’t be earning an income, two more years of my time in general.”

As a result of the advising fiasco, Manner said he switched to a public relations major because he could not afford to spend two more years in undergrad and another three in the PA program on top of that.

Laurie Goll, academic adviser in the College of Health Sciences, said Manner’s adviser has since left the university. Interim Provost Margaret Callahan said she cannot comment on student academic data.

Poor advising costs students time and money that they can not afford to lose as the economic recovery slowly continues.

While advising reform is obviously on the university docket, it is not something that can wait to be addressed. Students are getting nearer to graduation dates every day and many are unsure if they fulfilled all the requirements to receive their diplomas.

There are a number of initiatives the university could take to fix its advising problems.

Faculty advising does have its advantages, namely professional experience in the field and access to professional contacts. However, students in all colleges should have access to a team of full time advisers. Currently, the only college to have full-time advisers is the College of Arts & Sciences, and they are only assigned to students who have not yet declared a major.

DePaul University in Chicago, the largest Catholic university in the United States, has professional, full-time advisers in each of its seven colleges. Marquette should follow this method. Each student should be assigned a faculty adviser with whom they would be able to get career advice from in addition to a professional adviser that would focus on the completion of academic requirements.

The university cannot hold sole blame for students’ dissatisfaction with the advising process, even if the framework initiates many of the problems.

Students need to go into advising sessions as they would a study session or an interview – prepared with questions and a rudimentary knowledge of what they need to accomplish. College is a time of growing independence and self-discovery. Therefore, students need to take responsibility for their futures and be prepared going into advising sessions. The university should advertise this as they send out notifications for advising week.

Furthermore, if students are dissatisfied with advising, they ought to seek second opinions from other faculty members. While this would be much easier if all students had access to professional advisers, the lack of professional advisers should not stop students from taking the initiative themselves.

The university needs to revamp the way that it advises students, and students need not rely on the university to ensure their future academic success. Both students and the university should be more responsible for their respective part in the advising process.