Eddie Daniels, a South African anti-Apartheid leader, was sick and imprisoned from 1964 to 1979 in Robben Island with Nelson Mandela, the leader of South Africa’s anti-Apartheid movement and first democratically elected president of South Africa.

“We didn’t have flush toilets, in our cells, so we had buckets,” Daniels said Monday evening while speaking in the Raynor Memorial Library Beaumier Suites. “Mr. Mandela comes into my cell; he puts his bucket on the floor and comforts me. Then he gets up, picks up his bucket on his one arm and my bucket on the other arm. He walks down to the common toilet, empties my bucket, cleans my bucket and brings it back to me. Mr. Mandela, an international figure, leader of the African National Congress, helped me, a non-entity.”

Apartheid, a system of racial segregation enforced by the government, officially ended, and democracy became South Africa’s form of government, in 1994. Four years prior, in February of 1990, Mandela was released from prison.

It was Mandela who set the precedent for peaceful reconciliation as president of South Africa.

“When he had the enemy at his feet, he could have smite them down, but he didn’t. And that is the greatness of Mr. Mandela,” Daniels said.

Apartheid was not a new institution; it was officially instituted by the South African National Party in 1948.

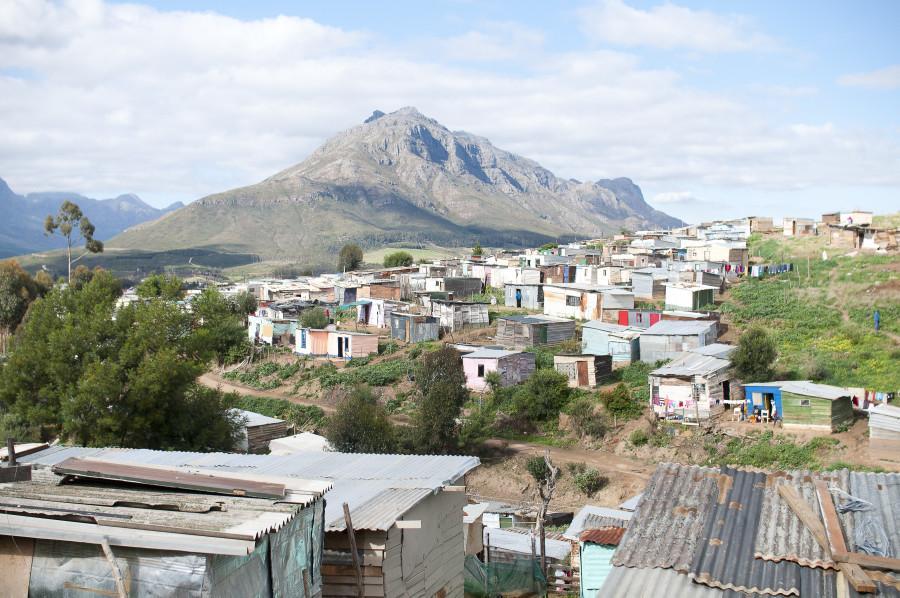

“I was born in a very poor area in District Six,” Daniels said. “With that poverty comes crime, gangs, and other unpleasant things.” Eventually, his family had to move because of gang violence and threats to his life.

District Six is a poor area in Cape Town, one of South Africa’s largest cities and the location of Marquette’s South Africa study abroad program.

“District Six is a physical reminder of the apartheid era,” said Steven Hartman-Keiser, an associate professor of English and the academic director of the South Africa program this past spring. “Tens of thousands of families were forced out of this neighborhood and the area was bulldozed, but it has never been redeveloped. So you have these inexplicably open, empty spaces right next to the high-rises of downtown. A reminder of the people who should be there but aren’t.”

Despite the commitment to reconciliation between races almost twenty years ago, South Africa’s political situation remains fragile.

Most recently, mining strikes have plagued the country. The South African government’s response to the strikes has been criticized internationally due to the deaths of 44 people, including 34 miners killed by police.

“I think that some observers also fear that the strike and the police violence are legacies of the violence of the apartheid era and see the strike and the police violence as symptoms of political instability and an undermining of democracy,” said Susan Giaimo, a visiting assistant professor of political science.

“The values of Mandela are no longer alive in the South African government,” Daniels said. “If I had my way, I’d kick them all out.”

Despite these setbacks, Daniels remains optimistic.

“We’ve come a long way from Apartheid, we will overcome these crimes of today as well,” he said.

Marquette’s South Africa Service Learning program is one of many that strives to continue the reconciliation that makes South Africa a better place, Hartman-Keiser added.

“The South Africa Service Learning program is the most remarkable example that I have seen of the university and its students living out the mission of Marquette,” Hartman-Keiser said. “All of the best that a Marquette education can and should be happens in Cape Town every semester.”