I like to think I’m a pretty observant person. So I probably should have noticed all the red flags the cosmos were throwing at me as I tried to leave the country for spring break.

Early first semester, I decided to put my Spanish minor to use and sign up for an alternative spring break in Latin America with Marquette’s Global Business Brigades.

Our group of eight students was eager to work on a coffee farm in Honduras — until we realized the nation was still without a president after last summer’s coup d’état and the State Department had issued a travel alert. The Office of International Education didn’t like that very much. Strike one. Time for Plan B.

Plan B turned out to be a two-tiered project in Guatemala distributing drinkable water and maintaining a small macadamia nut farm.

I’m anaphylactically allergic to tree nuts. That means I better get to a hospital ASAP before my throat swells shut.

I learned at my eleventh-hour allergy test at Froedtert Hospital after my Minnesota in-network doctor messed up the results that macadamia nuts are tree nuts. In fact, on an allergy scale of one to four, I’m a red hot flaring four.

“And you want to go to a macadamia nut farm?” the doctor asked.

“Yeah.”

She just laughed at me.

Strike two.

Luckily our GBB adviser said I could focus on the water project all week to avoid deathly nut exposure. So I renewed my EpiPen prescription and asked my dad to send my passport, which he did – via regular U.S. mail. That means no tracking device. That means when I didn’t have my passport two days before we were to leave I had no idea whether it had been stolen or was just lost in Cleveland. Strike three.

Thirty-six hours before we left, I’d never been so happy to see a mail truck. Passport in hand, I breathed a sigh of relief.

I lived through Guatemala — nut project and all — and had an incredible experience. But I had no idea what it meant to have strikes against you until I met Miguel.

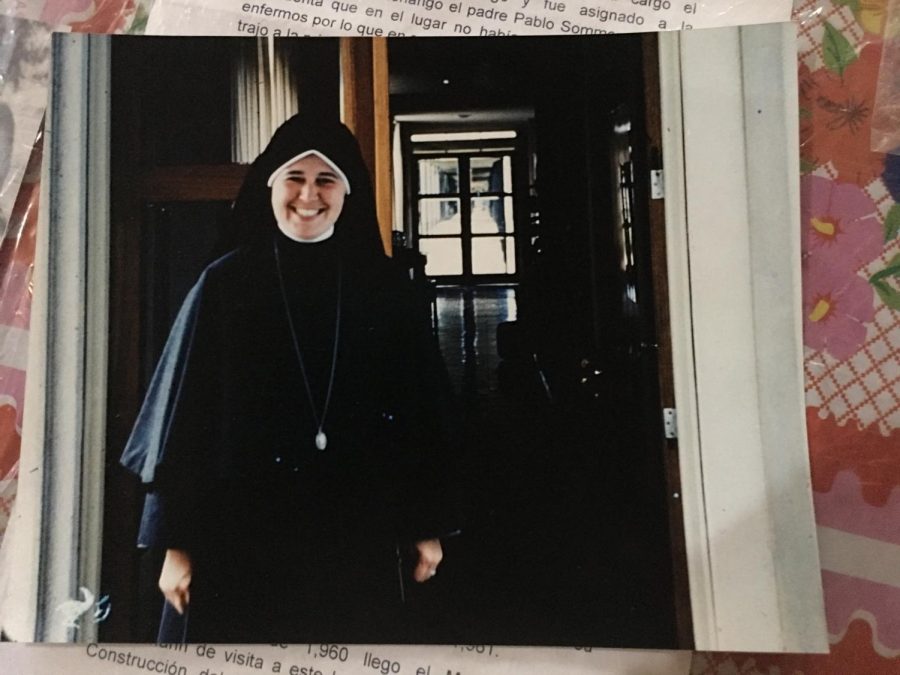

Miguel is a member of the Water Team from the Roman Catholic Diocese of Quiché in Guatemala. GBB worked with the team to survey the indigenous community of Patzalá, which was without access to drinkable water until four years ago.

Women and children used to haul jugs of river water more than 15 kilometers up a mountain. Now, the Water Team has installed a pump in the community to bring in pure water for drinking, cooking and washing.

GBB was to analyze the situation in Patzalá to determine whether similar projects would be sustainable in the dozens of Quiché communities still without drinkable water.

Miguel and other Water Team members brought us to Patzalá and translated the indigenous peoples’ testimonies from their native Quiché language to Spanish, which we then translated to English for our report.

Yes, our group was moved by the children who couldn’t go to school because they had to help their families collect water, the women whose children died of water-related diarrhea and the men who fought brutally with each other when the watering hole dried up. Their happiness and hospitality in the midst of poverty was stirring.

But most stirring was Miguel’s story.

Five years ago, Miguel had a run in with an electric saw that sliced off three of his fingers. Two years ago, he rushed home after a phone call from his sobbing wife to find their entire house had burned down. They have five children. The oldest is 14.

Miguel had to take out a loan to rebuild and repurchase his entire livelihood, from doors to pots and pans to underwear. The loan he took out has an interest rate of 10 percent — per month.

Just when Miguel realized he had no hope of getting out of debt, he and his wife got into a motorcycle accident. She lost her leg from the thigh down. Now, the 14-year-old is home from school and playing mamá by making the tortillas and caring for the other children.

So Miguel came to us, surrendering his pride entirely and asking. But he asked not for help with hospital bills or for full debt recovery. All he asked for was enough money to send two of his children to school, buy their uniforms and bus fare. This amount is $575.

We’d been working closely with Miguel for the entire week and had no idea any of this was happening. He has such a heart for the people, working with the poor even when he’s struggling himself. But Miguel was sure to add that he wasn’t the only one with hardships.

Everyone in Guatemala knows some sort of suffering, some kind of baggage that leads back to the 36-year Guatamalan Civil War, in which the government murdered unarmed indigenous civilians.

GBB is trying to raise funds to send Miguel’s children to school — e-mail me if you can spare a dollar or two — but first, look around. How many Miguels do you see walking down Wisconsin Avenue each day? These men and women have plenty of first-world strikes against them. I’ve found my Miguel to reach out to. I encourage you to find yours.

Wayne Milnar • Mar 30, 2010 at 9:36 am

Yolanda:

Great article! I have a question regarding interest rate. Is he really paying 10% per month or 10% per year? 10% per month would equate to 120% per year??!! Also, how do I contribute and to whom do I make the check payable?

As stated above,

Wayne