Many recent Marquette and University of Wisconsin-Madison law school graduates will find themselves in a unique position this month. While some law graduates throughout the rest of the country feverishly prepare for the grueling February Multistate Bar Examination, Wisconsin law graduates get to sit back and breathe easy knowing a Wisconsin Supreme Court rule from the 1800s allows many of them to practice law without ever taking the test.

Because of this, Marquette advertises a 100 percent bar passage rate without taking into account the passage rates of the students who have to take the test. Bar passage rates are often seen as one testament among several to the quality of a law school’s education, and Marquette is posing as the greatest in the nation in this regard despite coming in at 105th in US News and World Report‘s official law school rankings.

The Whole Truth?

Diploma privilege – the Wisconsin Supreme Court rule that allows graduates of Marquette’s and the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s law schools to practice law in Wisconsin without taking the bar if they meet certain requirements set by the state – is definitely something of a drawing point.

While it may sound too sweet to pass up, MULS graduates increasingly choose to practice law in states outside of Wisconsin. For these graduates, passing the bar is imperative in their pursuit to be legally admitted to practice law.

Kathleen Pagel, MULS Assistant Director of Academic Success and Bar Preparation, hypothesized that this increasing departure of graduates may be due in part to the increasing number of out-of-state residents enrolled at the law school.

“Over the past dozen years, as I understand it, we have gone from just over one-third of the first-year class being out-of-state residents to more than one-half this year,” Pagel said in an email.

Upon an initial search of the various ABA-required disclosures MULS submits every year, these particular bar passage rates cannot be found. Instead, the standard 509 Information Report of 2015 reads that the bar passage rates for both tests in 2014 was 99.50 percent, while the passage rates for both tests in 2013 and 2012 were a perfect 100 percent.

In fact, a quick look at certain websites like U.S. News and World Report, that rank law schools based on different criteria, will show both MULS and UW-Madison Law School top even the best law schools in the country for bar passage rates – with 100 percent. It should be noted that U.S. News’s bar passage rates lie behind a paywall, but other sites like StartClass do not.

Both institutions can report perfect numbers because, given the continued extension of diploma privilege by the Wisconsin Supreme Court, technically every student who graduates “passes” the bar, even though they are not required to take it at any point – assuming they meet the certifications and remain within state lines while practicing law.

It isn’t clear, however, whether this 100 percent passage rate includes all students, or only those who wish to practice in Wisconsin and take advantage of the diploma privilege. After examining dozens of other law schools’ ABA-required disclosures, most list the bar passage rates of several states where students most often take the exam.

Marquette lists only one: Wisconsin.

After contacting both the Illinois and Minnesota State Bar Associations – two states where many graduates choose to venture upon graduation – representatives from both institutions gave almost the same response: As a private institution, Marquette is not obligated to present that information to private individuals.

The Directors of the Board of Admissions to the Bar and the Board of Law Examiners of each of these states, as well as Wisconsin, corroborated this roadblock: This data is compiled but cannot be released to private individuals.

Yet, the data is reported to the law schools and then reported to the ABA.

A final inquiry to Erica Moeser, president and CEO of the National Conference of Bar Examiners, left all roads pointing in the same direction: “Concerning the data you are looking for, Marquette law school would be the only one to have that, if anyone.”

However, Pagel said, “We do not compile this data.”

Lowering the Bar

One troubling aspect of this is the overall decline in bar passage rates nationwide. If law schools across the country are struggling with passage rates more than in the past, it is difficult to assume Marquette would be immune to this if most students did have to take the exam.

Nationwide, scores on the MBE dropped to a mean score of 141.7 in 2014 – nearly three points lower than the national mean for the July 2013 exam. This marked the single biggest year-to-year drop since the start of the MBE. July 2014’s score was the lowest national mean MBE score in 10 years.

Some fear this is only the beginning of a more disturbing trend. Just a year later, the average score on the multiple-choice portion of the July 2015 test was 139.9, down 1.6 points from 141.5 in July 2014; its lowest level since 1988, according to data provided to Bloomberg by the National Conference of Bar Examiners.

But because Marquette and UW-Madison law students don’t have to take the bar, it remains a mystery how they might have fared.

Closing the Gap

A major reason law graduates struggle to pass the bar is because law schools are accepting students with lower qualifications than past years in order to keep enrollment numbers up.

Over the past decade, the number of students applying to law school decreased significantly. This decrease was most pronounced in 2011-’12, when the weak legal market and law school dishonesty came to the forefront of national news. According to prospective student data by admissions cycle and for ABA-approved schools since the 2002-’03 academic year, the number of applicants dropped by almost half, from 99,500 applicants to only 55,702 applicants in 2014-’15.

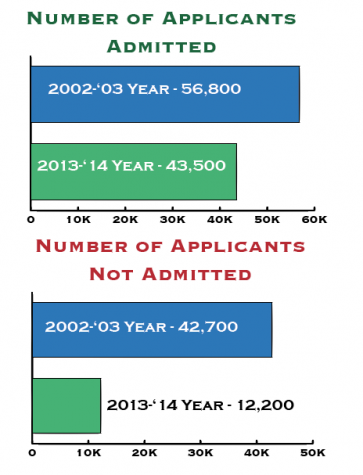

Consequently, the gap between the number of applicants and those accepted narrowed noticeably. While 56,800 applicants were admitted to law school in 2002-’03 compared to 43,500 in 2013-’14, 42,700 applicants were not admitted to law school in 2002-’03 whereas only 12,200 applicants were not in 2013-’14.

This means getting into law school became easier over time, specifically over the past decade. According to the same admissions cycle data, 57.1 percent of applicants were admitted to at least one law school in 2002-’03, whereas 78.1 percent of applicants were accepted in 2013-’14.

“Enrollment hasn’t caught up, and some students are at a greater risk of not passing,” Moeser said.

Enrollment at MULS is down significantly, with only 178 enrolled students entering the fall 2015 J.D. class compared to 208 in 2014, 209 in 2013 and the 10-year high of 247 enrolled students in 2010.

“Less qualified,” not “less intelligent”

Derek Muller, a professor at the Pepperdine School of Law, said in a Bloomberg Business article that law schools have relaxed their admissions standards and have “started filling their campuses with students who are not as qualified as they used to be,” in order to maintain enrollment figures.

He’s talking mainly about LSAT scores and undergraduate GPAs. These are key indicators of a student’s qualifications, ability to succeed during and after law school and ability to pass the bar.

LSAT scores also tend to correlate closely with success during the first year of law school and with scores on the bar exam, “so when schools admit lower-scoring students on the former test, they risk producing more graduates who have a hard time passing the bar,” according to a Bloomberg Business article.

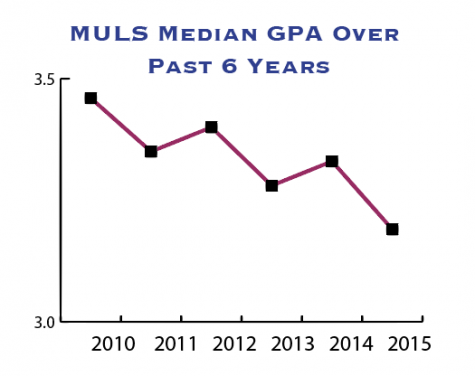

Marquette’s median LSAT score and GPA for 2015 entering law students is 152 and 3.19 respectively. In 2011, the median LSAT peaked at 157, and the median undergraduate GPA was 3.46.

Joseph Kearney, dean of the Marquette law school, said in an email that the significance of the decline in scores should not be overstated.

“At the same time, like a number of schools, we are taking steps to reduce the size of the entering class,” Kearney said. “In all events, it is difficult to see how a downward trend over the past five years or so, coming after historic highs, would lead to a change in the bar admission policy that has served Wisconsin well for nearly a century.”

Steps in the Right Direction

Despite MULS’s lack of data, Pagel said the law school hired her last year as the first in the position at Marquette, “primarily to support the increasing number of MULS students who will take another jurisdiction’s bar exam.” Pagel also teaches a class focused on developing and enhancing students’ skills in order for them to be more successful on the essay portion of the bar examination.

Additionally, Pagel is working to develop a bar preparation program that will support students during the summer after they have completed law school and are preparing for the exam.

“I plan to schedule several workshops and mock bar exams over the summer to help prepare MULS students for the MBE and performance test portions of bar examinations,” Pagel said.

When asked if students seem to struggle with the bar exam lately, Pagel responded, “It’s hard for me to say.”

She also said she doesn’t think diploma privilege undermines the quality of practicing lawyers in Wisconsin.

“We believe that in continuing the diploma privilege over time, the Wisconsin Supreme Court has shown great confidence in MULS’s ability to adequately prepare its students for the practice of law in Wisconsin,” Pagel said in the email. “We commonly hear from the lawyers who employ our graduates that our students are ‘practice ready’ and contribute to the success of the firm from the time they join the practice.”