Rhetoric surrounding this year’s layoffs and budget cuts echoed a common theme: Growth in administration at Marquette over the past decade is unsustainable, and leaders are taking action.

“We had added about 300 people over the past 10 years and an organization can’t just continue to add,” said interim University President the Rev. Robert A. Wild in his State of the University address. “You have to take a look and see whether we can operate more efficiently.”

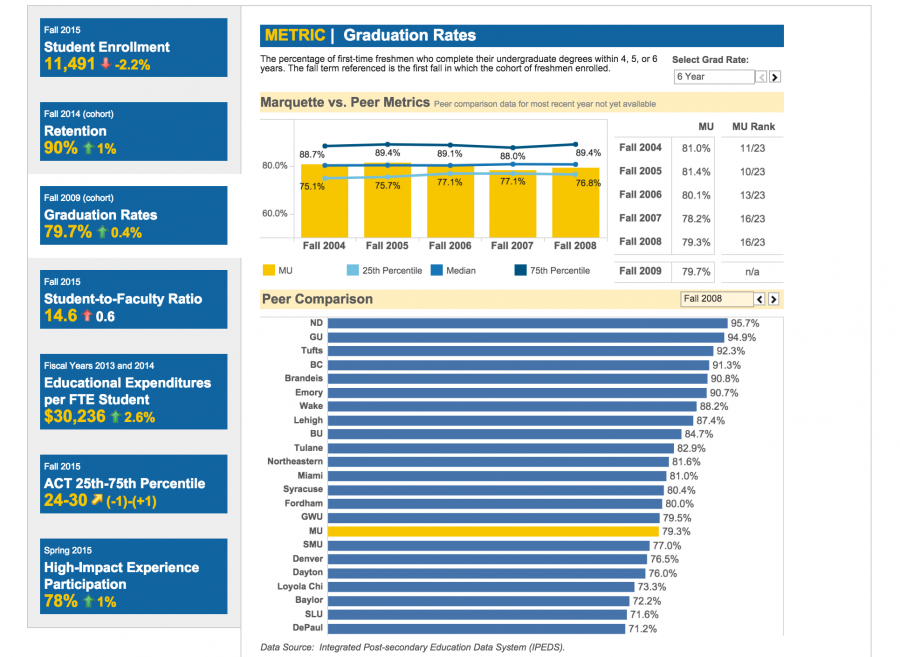

The bloat in administrative positions follows national trends, adding to skyrocketing tuition costs across the country. The size of Marquette’s non-academic administrative and professional employees increased 43 percent from 1993 to 2011, according to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System.

Newly released cost breakdowns for Fiscal Year 2015, however, show that administrative expenditures will take up a slightly smaller percentage of total university costs next year. With 25 staff members laid off from the university and another 80 positions expected to be absorbed through retirements or not filling open positions, university officials made reducing staff costs a budgetary priority.

“Marquette has responsibly managed its budget and has operated with a positive margin the past 16 years,” said Vice President of Finance John Lamb in an email. “We fully expect that will be the case for the current fiscal year, as well as future years, because of the proactive steps university leadership has made.”

Still, some remain skeptical of the effectiveness of cost-cutting measures. Richard Vedder, an economist and director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, cautioned students about taking administrative statements at face-value.

“There’s a lot of rhetoric — a lot of huffing and puffing about savings,” Vedder said. “They’ll brag about efforts to cut costs by switching to cheaper light bulbs yet staff lines will continue to rise.”

MU’S ADMINISTRATION

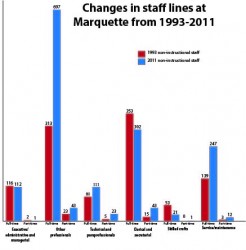

In all, Marquette added almost 450 full-time positions and more than 60 part-time positions between 1993 and 2011 – the most recent academic year for which comparable figures are available. These numbers include any staff other than instructional faculty or graduate assistants.

Following rhetoric from university leaders about administration jumps, it might be expected to see a large increase in the IPEDS category of “executive/administrative and managerial.” However, Marquette’s staff size remained about the same from 116 full-time employees in 1993 to 112 employees in 2011. Similarly, other categories like “skilled crafts” and “clerical” did not change much. Technical positions increased marginally as expected with the increased use of technology in higher education.

The category of “other professionals,” on the other hand, saw a 122 percent increase in full-time positions, from 313 people in 1993 to 697 in 2011.

According to the IPEDS website, “other professionals” is an umbrella term to “classify persons employed for the primary purpose of performing academic support, student service and institutional support.” Included in this category are employees holding a range of titles including business operations specialists, human resources, meeting and convention planners, accountants and auditors.

“(Those positions) do nothing related to research or students,” said John McAdams, a professor who joined Marquette’s political science department in 1997. “They hold a lot of meetings and do a lot of planning.”

McAdams expresses an attitude found among many vocal critics of Marquette’s administrative structure, and of higher education as a whole.

“It’s bureaucracy run amok,” Vedder said

According to staff and faculty figures from the Office of Institutional Research and Analysis, there are almost twice as many non-academic employees as there are instructional positions at Marquette. It is important to note, however, this ratio has not changed much since 2004, the latest data available.

BEHIND THE INCREASE IN STAFF SIZE

Adding services beyond teaching and research fuels the growth of campus payrolls. Lamb said 65 percent of the university’s budget is personnel costs, including salary and benefits.

Throughout the nation, most universities’ fundraising and marketing departments pay for themselves. Several others created only recently, such as those focusing on sustainability, gender and sexuality issues and diversity, cost the university a large chunk of change, Vedder said.

In addition, Vedder said universities blame the increased departments and hiring on government regulations. Financial aid alone has a slew of mandates for accredited institutions so each university has at least one person, or in some cases, whole office staff, dedicated to this task.

“But the numbers seem inconsistent with the idea that external mandates have been driving administrative growth at America’s institutions of higher education,” said Benjamin Ginsberg, a political science professor at Johns Hopkins University, in his 2011 book, “The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters.”

Nationally, universities cite demands from students and families as rationale behind their swelling staff numbers. Students recently started to receive services like remedial education, advising and mental-health counseling.

“(Universities) will claim they face so many demands,” McAdams said. “But most of the stuff they do is their own initiative.”

McAdams used the example of strategic planning, an extensive process colleges endure to receive accreditation.

“There’s no demand for this but we (Marquette) have to do it because other schools do,” he said. “It’s an excuse for a bigger bureaucracy.”

Andrew Brodzeller, assistant director of university communication, however, said the administrative positions “represent and support Marquette’s mission.”

“Directly or indirectly, Marquette employees help support the education of our students,” Brodzeller said in an email.

A HISTORY OF MU’S ADMINISTRATION

The data from IPEDS has a few faulty years, but this can be attributed to different definitions among schools.

“Some schools may see a standout year where people might be re-classifying staffers into different categories,” Vedder explained.

To reduce this ambiguity, IPEDS will increase its number of categories from nine to 18, said Alexandra Riley, director of the OIRA. Even though the data was collected by different departments in the past and some years may throw off the trend, Marquette’s administration is growing.

To verify this, the Tribune analyzed phone directories dating back to the 1960’s and compared the number of employees within each department throughout five decades.

For example, in the 1956-57 school year the Office of Academic Affairs was comprised of two people: the vice president and assistant to the vice president. Ten years later this office included a vice president, associate academic vice president, assistant vice president, administrative assistant and two administrative secretaries. This office was discontinued in 2002 and many departments were transferred to the Office of the Provost. Today, this office houses the provost, a special assistant to the provost, an executive administrative assistant, two vice provosts, one vice president, four associate provosts, three administrative assistants, and two directors.

The Office of Continuing Education displays a similar trend. In the 1960s, this office was run by six people – a director, three assistant directors and two assistants. Like the Office of Academic Affairs, it received a restructuring and is now called the Office of Professional Studies. Today, 16 people work in this office.

“They find work to do,” Vedder said. “They produce forms for people to fill out that they didn’t used to produce. They count things they didn’t used to count. They justify their existence.”

A NATIONAL TREND

The long list of bureaucratic titles extends beyond Marquette’s campus and permeates almost every other university. According to Ginsberg, the number of administrators and managers employed by private colleges and universities grew by 135 percent.

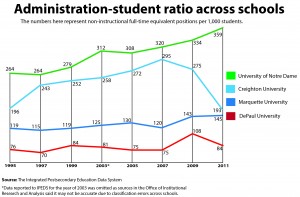

The Tribune analyzed data from four other Catholic schools – DePaul University, the University of Notre Dame, Creighton University and Loyola University of Chicago.

Each school saw a significant increase in non-academic administrative and professional employees from 1995 to 2011. DePaul University experienced the largest increase, 91 percent, while Creighton only saw a 24 percent increase. Marquette had the second smallest increase in administration size, coming in at 38 percent.

But the analysis gets more interesting when student size is factored into the equation. For every 1,000 students, the University of Notre Dame comes in first with 359 employees. Marquette again fell somewhere in the middle with 145 administrative staffers for every 1,000 students.

However, Marquette experienced the second highest increase with 34 percent in student-to-administrative staff ratio. Creighton University actually experienced a small decrease in staff size after numbers in the early 2000’s swelled. This suggests the Nebraska school is actively seeking to eliminate unnecessary roles.

GROWING ON THE BACKS OF STUDENTS

The number of non-academic and professional employees at U.S. colleges outpaced the growth in the number of students or faculty, according to an analysis of federal figures. The exorbitant growth slowed only slightly since the start of the economic recession, but was met with an increase in tuition at most universities.

Marquette tuition increases every year to keep up with the rising costs. Between 2003 and 2013, Marquette’s per-semester undergrad tuition increased by 76 percent, but when adjusted for inflation, increased by about 36 percent. In the university’s Financial Overview, the Office of Finance identified one of the key cost drivers as labor — yet several of the university’s administrators are paid yearly salaries upwards of $300,000, according to Marquette’s 990 tax form.

“There’s so many assistant-this and associate-that,” Vedder said. “We don’t really know what those words mean and what those people do let alone what it has to do with teaching kids.”

Regardless of the efficiency of the positions, however, the cost of bureaucracy is a ongoing concern for students.

“How much are these new positions benefitting students?” asked Christina Hoehn, a freshman in the College of Health Sciences. “If they’re not benefitting us, then why are we paying for them?”