Last week, our campus hosted a variety of speakers, one of whom was conservative commentator and columnist Ben Shapiro. While his visit produced some controversy — a bit of which he highlighted in his talk — we, as a university, should not avoid controversy. A university, and a Jesuit one in particular, should be a place to search for the truth, in part through expressing and entertaining differing ideas, even those strongly in opposition.

Entertaining those ideas, though, does not mean we shouldn’t challenge them when we disagree. It is in that spirit that I wish to offer a challenge to the Marquette community to not simply listen to speakers for the sake of listening, but to also think critically about what they’re saying, and in some cases respectfully test their claims and assertions. After all, that is one of the promises of a liberal arts education: to help students become critical interrogators of the information and opinions we constantly receive from friends, family, media, pundits and political leaders.

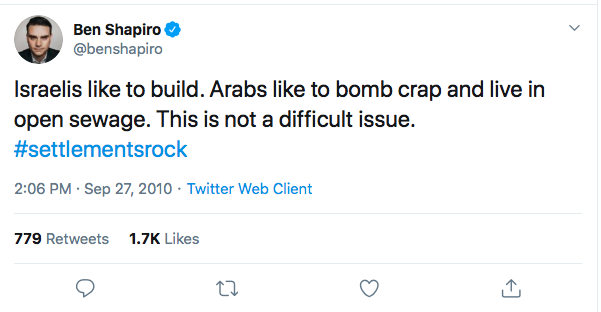

As an exercise, let’s take a more critical look at one of Shapiro’s key claims: There is no institutionalized racism in the United States. There are, he admits, individuals who are racist and do racist things, but there is no structural discrimination that victimizes people because of race. He also concedes institutionalized racism existed 40 to 50 years ago, but, he says, that is now gone.

There is a lot to address there, but let’s focus on three critical questions before we express agreement. First, has the institutionalized racism of yesteryear really disappeared? Take one instance in our own world of higher education. It is widely accepted that back in the bad ol’ days, universities had racist recruitment and admissions practices that severely disadvantaged African Americans. That disadvantage is gone in our new enlightened era, Shapiro says.

But is it? Consider this: Almost all universities have long had recruitment and admissions practices that target legacy students (the children and relatives of its alumni). If the parents or grandparents were admitted using a racist standard, then doesn’t the legacy advantage replicate that racism in the next generation? Haven’t these legacy practices built racism into the access to higher education? Maybe it’s possible that racial advantages still exist more than we think.

Another Shapiro claim is that there are individual racists, but that does not mean there is any kind of structured racist system. That begs the question: Where does individual racism end and structural racism begin? If those racist structures that we agree existed in the past were the result of individuals enacting racist ideas, when do these bad individuals have enough influence to make the system racially biased?

Does a company become racist if the CEO is one of these bad people? How about if a group of racists gets control of the board of directors? What if such people become influential on a school board — will the school system become racist through the decisions they make and the policies they create? What if such people become elected leaders? Can we really be so sure that these individual bad people, who we agree exist, aren’t finding ways of enacting their racism through our institutions?

I offer a story from my own life to illustrate: When I was growing up, the state where I lived sponsored an all-state high school choir. Students from all over the state vied for membership as the choir traveled around the world, singing at various events and for dignitaries. As it happens, the choir director was one of those individual bad people. We learned after his death that he had, for years, asked applicants to submit a picture so he could weed out the Black kids. After his superiors made him stop asking for pictures, he then tried to guess the race of the applicants based on their last names!

That was individual bad behavior, Shapiro would likely agree. But that individual, by virtue of his position, created structural discrimination. By his hand, the state government was enacting systemic discrimination. Doesn’t that make it hard to simultaneously contend that we have individual racists out there, but we do not have any institutional racism?

By denying institutional racism, Shapiro can boil racial differences down to individual agency: if Black people just tried harder and made better choices, they’d do just as well as Whites. Simply finish high school, avoid early pregnancy and get a job. If you do, you’ll be OK. Seems reasonable, but let’s pause again. Does everyone (regardless of race, income, where they live and family circumstances) have the same chance to finish high school? Does every high school produce the same results (learning, skills and chances of getting into college)? Does everyone have the same chance of getting a job? If the answer to any of these questions is “no,” we must rethink whether individual agency is the only thing that matters.

Let’s dig further into employment. Shapiro implies that everyone can simply choose to have a job. Are we sure that’s the case? In 2007, the White unemployment rate in the U.S. was just under 4 percent. By the middle of 2009, it had jumped up to 9 percent. Was this change due to individual choice? Did 5 percent of the White workforce just decide to quit working? The more likely explanation is that there were structural economic changes (namely, a recession) that caused that job loss.

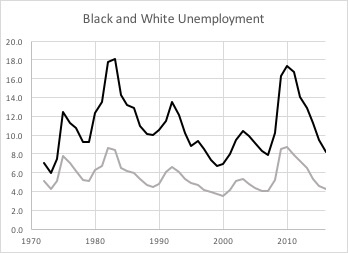

If a structural explanation is the likely one for Whites, why not for African Americans? As long as data has been collected, Blacks have consistently suffered about twice the unemployment rate of Whites (see graph). But it’s not as if African Americans won’t take the jobs if they are there. In 2007, Black unemployment went down to under 8 percent, lower than the rate for Whites just two years later. Were Whites in 2009 lazier and less responsible than Blacks were in 2007? If not, are these patterns really all about individual choice?

Inevitably, talks on our campus — similar to Shapiro’s and not so similar — will raise a lot of questions. And we could conduct this same critical thinking exercise for any number of our guest speakers. Some of their claims will stand up well to further scrutiny, and others won’t do so well. But, as seekers of truth, we need to demand that they do.

Healthy skepticism is at the very foundation of active learning. We should be suspicious when we hear that “it’s simple” or “it’s obvious.” Those are the exact moments we must think critically and start cross-examining what may appear simple and obvious. More often than not, it’s neither.

Dan Myers is the University Provost.

He can be reached at daniel.myers@marquette.edu