Daniel Bernard uses his Federal Student Aid refund to pay four months’ rent up-front. With what remains, he buys a new pair of blue wingtip boots, which had been patiently waiting in an online shopping cart. His clothing is often representative of his professional, approachable demeanor: he irons a button-up dress shirt – usually blue – and he pairs it with a knit cardigan – usually red. The color scheme coincidentally aligns with his deep passion for U.S. government and his desire to influence it one day. Always expressive, he keeps a handful of five-dollar words in his back pocket for use during hyperbolic reenactments of the week’s events. He gets up early, stays up late, drinks a lot of coffee and goes out on the weekends. He’s sarcastic, uses colloquial slang like “lit” and shares ironic memes on social media.

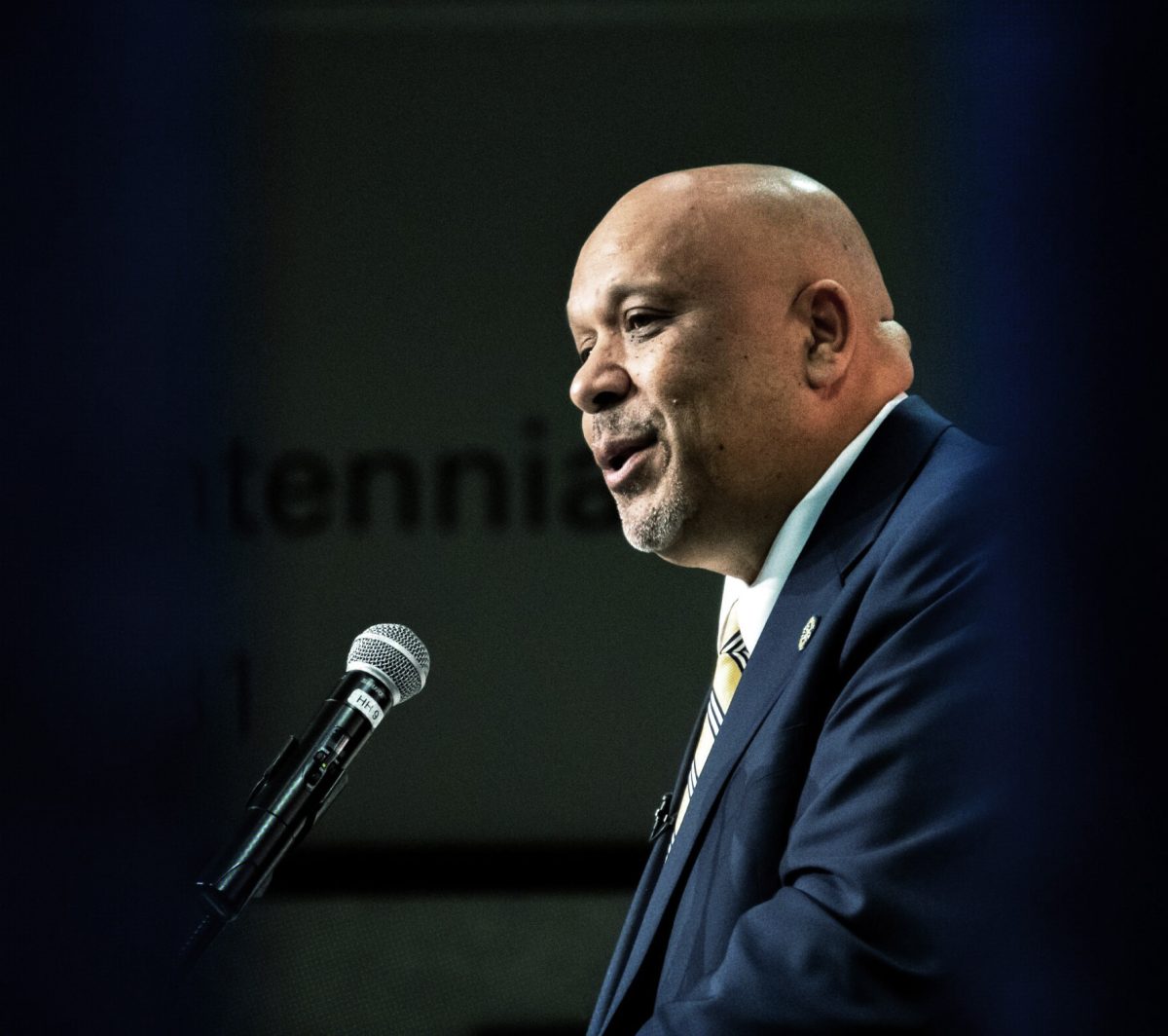

Photo by Maryam Tunio

Photo by Maryam Tunio

Bernard, a senior in the College of Arts & Sciences, is the poster child for the “relatable college kid,” or at least he would be if his father was not West Indian and his mother Puerto Rican. Bernard isn’t white, so his personality comes second to his skin tone. A conversation Bernard had during his freshman year solidifies this.

“He told me that I was one of the whitest people that he knew,” Bernard said, shaking his head, still in disbelief four years later, recounting which traits his then-roommate attributed to whiteness, “Ironing my clothes, reading the newspaper, I use big words, I don’t have an accent, I’m clean, I’m smart.”

I react to this with shock and associative guilt. Bernard reacts with a lesson learned. “These people will think what normal equals white, (but) white people don’t have a monopoly on civility.”

With the Supreme Court making an affirmative action ruling this summer and efforts by Marquette and other schools around the country to recruit more diverse student and faculty communities, it’s no secret that universities have struggled to engage appropriate numbers of minority members. Marquette diversity reports show, albeit slowly, campus is becoming more diverse and more accessible. In the last five years, Marquette has increased minority enrollment by eight percent.

However, compare that progress with the climate study published in September of last year and a very different narrative emerges. According to that study, one-third of the Marquette community reported at least observing acts of exclusion or hostility on campus. It also noted that a significantly lower percentage of African American, Hispanic and multiracial respondents and respondents of color were “very comfortable” with the overall climate at Marquette compared to white respondents. Clearly, an increased minority presence on campus alone does not ensure a welcoming, inclusive environment overall.

Socially, minority students are still ostracized by a society that caters to hegemonic white masculinity. The weekend offers reprieve from early lectures and D2L discussion posts, but unfortunately latent prejudices are only augmented by apartment pre-gaming and Saturday keg races.

According to the climate study, 150 respondents said they considered leaving because of feelings related to inclusion and exclusion. One wrote, “This is a very niche driven school. The community is perfect for those who fit the criteria. For those who fit the standard the school is amazing, but for those even slightly out of it, it can be very frustrating.”

Manny Hurtado, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences said he can relate. “It’s happened a couple times where I’ve been asked when entering a party if I go to Marquette,” said Hurtado, a member of Marquette’s Gender Sexuality Alliance and Marquette’s Urban Scholars, a university program that aims to promote inclusivity and diversity.

Photo by Maryam Tunio

Photo by Maryam Tunio

What Hurtado has too often encountered is that because of his ethnicity, people don’t automatically connect him to the university.

He says he gets questioned every time he wears something with Marquette’s logo.

Bernard, who worked as a Resident Assistant for two years, said that minority residents used to complain to him about Marquette’s LIMO service, which tends to ask non-white students to show their university IDs, but skips this formality for white student riders.

These presumptions aren’t purposeful. What most people think when they think Marquette is affluence, and what most people think when they think affluence is white.

“People think of (Marquette) as unattainable,” said Josh Miles, a junior in the College of Communication and co-chair for the President’s Task Force on Equity and Inclusion, a group of students, staff, faculty and community members that was formed to complement university diversity initiatives. “Being a minority, (people) have that automatic surprise like, ‘Oh my God, you’re doing all these great things.’ Yeah, I am. That’s what you’re supposed to do.”

Lyphenia Bryant, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, points to a much less subtle situation: “My roommate was like, ‘Oh you don’t have loans? That’s because you’re black.'”

Hearing these students’ personal accounts of micro-aggressions that minority students are so used to experiencing shows a deeper systemic problem. Climate study results support their claims: 44 percent of African American respondents and 29 percent of Hispanic respondents indicated they had experienced exclusionary, intimidating, offensive, and/or hostile conduct at Marquette. For white respondents, this figure was 15 percent.

How do we get the Marquette community to understand and empathize better to minimize these micro-aggressions and purposefully avoid exclusive behavior?

“I always tell people; you need to be your biggest advocate, you need to tell people when you feel like you’re being mistreated,” Miles said. “I don’t think most people are horrible human beings, I just think that most people are ignorant.”

It’s odd to use to ignorance to justify this serious issue that affects so much of our campus community, but Miles has a point. I consider myself socially conscious and sensitive to experiences outside my own. I was even genuinely surprised by some of the interactions different students have had. What’s more, I’ve absolutely perpetuated racially aggressive behavior without realizing it.

White members of the Marquette community aren’t intrinsically part of the problem, but being defensive about the associated privilege is. Inclusion matters, and everyone has the duty of contributing to a welcoming atmosphere, in and out of the classroom.

Our role as students is to be constantly learning, and that extends to social learning as well. The responsibility to hold one another accountable goes beyond our role as students and beyond our role as members of the Marquette community. It’s our role as humans to try to make other humans feel accepted and appreciated, and also to acknowledge when their experiences differ from our own.

Miles summed up the discussion with intelligence and hope, “Empathy is something we all have to do better.”

Photos by Maryam Tunio

Photos by Maryam Tunio