Samantha Kennedy is no ordinary Marquette student. At first glance, she may seem like just another face in the crowd, just another person going to the Marquette games and just another student taking notes in class, but in reality, she juggles her daily life with her life as a competitive, Olympic-bound hammer throw athlete.

The hammer throw is a technical track and field event that requires extreme discipline and precise movements. Kennedy competes on the Marquette track and field team, training during the year with a throwing and lifting coach with additional support from her coach at home, who has trained her since she was 16 years old.

“In hammer, you have to be fully relaxed to throw, so if you’re really high strung, it’s not going to work for you so a lot of times I just breathe and pray, which works for me,” Kennedy says.

Hammer throw is a unique and non-traditional sport, and Kennedy spent her childhood unaware of her amazing talent. She discovered it accidentally after an after-school spring sport didn’t work out.

“My family is very into baseball, so I was put into baseball [as a kid] because my older brother was in it, and my younger brother got into it too, but I was terrible at it,” Kennedy says. “I was so awful – I just didn’t have the attention span for baseball and I’d always be in the outfield because I wouldn’t pay attention to the infield. I did ballet at the same time, so I would be doing pirouettes and dances in the field.”

With baseball not going according to plan, Kennedy started looking to other sports to occupy her time and soon discovered track and field through a girl at her church.

“I thought going in that I could run and be a runner, because our school would go to cross country meets and I did fairly well at them, but I didn’t like that for very long,” Kennedy says. “I did get into hammer [throw] that year, though. That was the year I turned 12.”

By the time she was 15, Kennedy’s talent for the hammer throw was so evident that the throwing coaches at her club had to admit to her that they had nothing else to teach her. Kennedy spent a year training on her own without the guidance of a coach – a year that helped to focus and discipline herself before she found a coach qualified to train her.

The talent, discipline and dedication to her sport paid off, and in 2012, Kennedy, a resident of British Columbia, won the gold medal for hammer throw at the Canadian Junior National Track and Field Championships. Her record is stellar, but Kennedy has set her sights on bigger goals.

“For this upcoming season, I’d love to go to regionals, place in the top 12 and then go to nationals. That’s the end goal,” she says. “This summer, I hope to make Team Canada to compete. Once I’m done at Marquette, I’m planning to move to a training center in British Columbia to stay for about five years to see if I can make the Olympics in 2016 and 2020.”

Kennedy is already a veteran member of Team British Columbia, having made it when she was 16 and 17 where she subsequently won Youth Nationals both years. During her junior year of high school, she placed second her first year as an 18 year old, and later won as a 19 year old during her freshman year at Marquette.

Juggling academic life and Olympic-bound life is incredibly difficult with strict training session five days a week, but Kennedy is quick to say that she can handle the workload.

“It is a lot, but I’m a very organized person and I schedule things very efficiently and know exactly what I need to do each day so I’m not overwhelmed,” she says.

Balancing life as a track and field athlete with school life is a common occurrence in the sport, according to Kennedy. The men and women she trains with in Milwaukee are also in school, and at her track club at home, most athletes are college-bound high schoolers. A lot of the athletes she’s been on Team Canada with are also college students in the United States.

“A lot of higher Canadian athletes will go to the States to train to compete on Team Canada because Canada doesn’t give good scholarships and the U.S. competitions here are tougher and good for training,” Kennedy says.

She is right about the scholarships; Kennedy has a full-ride to Marquette.

“I love being a part of something that’s not just you, I love being a part of a team,” Kennedy says. “Traveling can be fun too, especially when we go places like Florida or California, so there are a lot of fun aspects to it.”

Kennedy has a full schedule with academics and athletics that can be difficult to understand, but one member of the Marquette community who understands her commitment to competitive athletics is Brian Hansen, an Olympic speed skater taking a break from Marquette to compete in Sochi.

Hansen has already graced the Olympic podium, winning a silver medal in the 2010 Vancouver Olympic games in team pursuit. Team pursuit is a form of speed skating where teams of three skaters make a total of eight laps around a track, and race against another team of three at the same time. Hansen took a year off between high school and college in order to train, and he balanced his freshman year at Marquette with competitive speed skating.

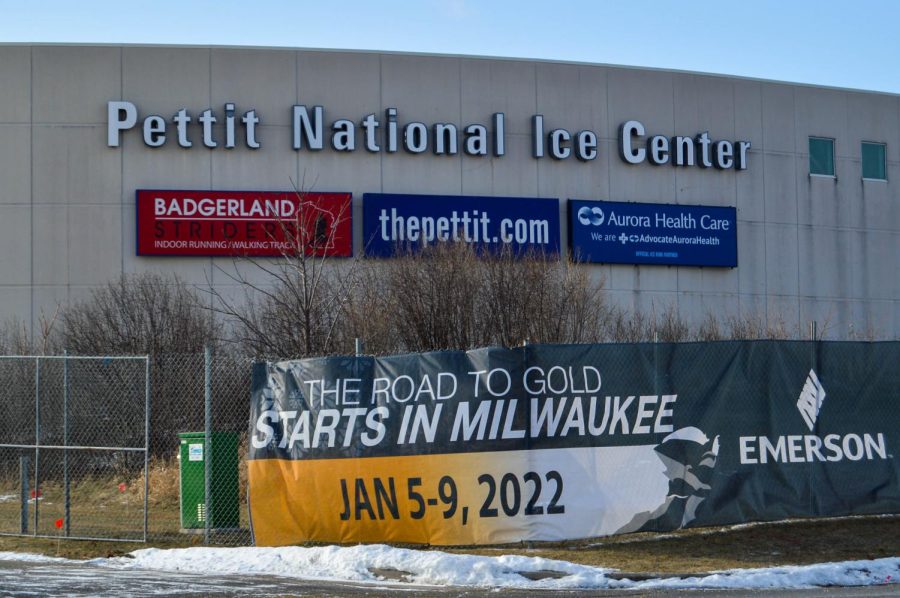

Training is intense, and Hansen spends almost 10 hours a day skating at the Pettit National Ice Center in Milwaukee. The training made it difficult for him to juggle his athletic life with his academic one at Marquette during his first two years as a college student.

“In order to be competitive, I have to travel internationally about nine times during the school year, not including how much I travel within the United States,” Hansen says. “That’s why I’m taking a leave of absence until after the 2014 Olympics. I want to be able to fully focus on my studies.”

Hansen’s choice to take time off from school was not easily made.

“I wouldn’t take time off if I didn’t have to,” he says. “I tried the whole training thing while taking classes, and it was really difficult to keep up with everything, especially since I have to travel a lot.”

In 2012, Hansen traveled to Russia, Kazakhstan, Germany, Brazil and the Netherlands twice, all while taking classes at Marquette. Marquette has allowed him to take a leave of absence in 2013 to focus on his training.

“Marquette means a lot to me,” Hansen says. “I try to stay as involved as possible on campus, even though I am on leave to train.”

For Hansen, being involved in the Marquette community means supporting the presence of other on-ice sports at Marquette, such as hockey and figure skating.

“I go to as many games as I can,” he says. “I spend a lot of time as an athlete, but I love being in the stands too.”

Hansen spends most of his days on a strict training schedule given to him by his coach of 12 years, Nancy Swider-Peltz. Swider-Peltz’s daughter, Nancy Jr, and son Jeff also train with Hansen at the Pettit Ice Center, though neither of them are enrolled in college.

“Training with Nancy, Nancy Jr and Jeff is fun,” Hansen says. “We all started out together in Glenview, Ill., and we used to commute to the Pettit in Milwaukee every day while we were in High School.”

The training team was forced to commute to Milwaukee on a daily basis because the Pettit National Ice Center is one of only two ice arenas in the United States with a long track ice rink, which means that competitive speed skaters can only train in Milwaukee or Salt Lake City.

“We didn’t want to go to Salt Lake City,” Hansen says. “We are really the only competitive speed skaters in Milwaukee right now, though, with the exception of one or two others. Most go to Salt Lake City, but we wanted to stay closer to home, and we like Milwaukee.”

Despite wanting to stay in Milwaukee, Hansen ended up spending almost four weeks in Salt Lake City last year. He attended smaller competitions in preparation for the World Speed Skating Championships.

“I had to go (to Salt Lake) a lot last year, ” Hansen says. “But I’ve always come back to Milwaukee, and I’ll always come back to Marquette.”