Charlie Kubly was described by his loved ones as the life of the party, even as he battled depression for years.

He was 28 when that battle ended and Kubly lost his life to suicide.

Kubly grew up in Milwaukee as the youngest of seven children. In high school and college, he spent time traveling, skiing, sailing and playing tennis. He loved blues music and was getting his pilot’s license.

After he graduated from St. Thomas University with a degree in entrepreneurship, he worked on starting his own company called “Care by Air” — a business for family and friends to send care packages to college students.

Yet even as he moved forward in life, his mental health concerns kept him from happiness. He sought professional help after college, trying various treatment options, but nothing seemed to work.

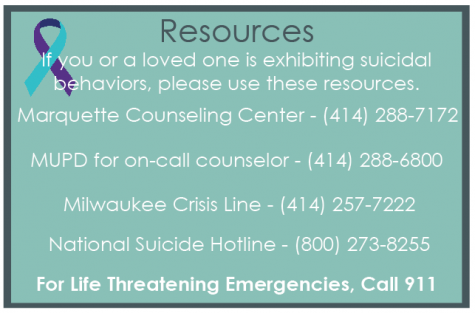

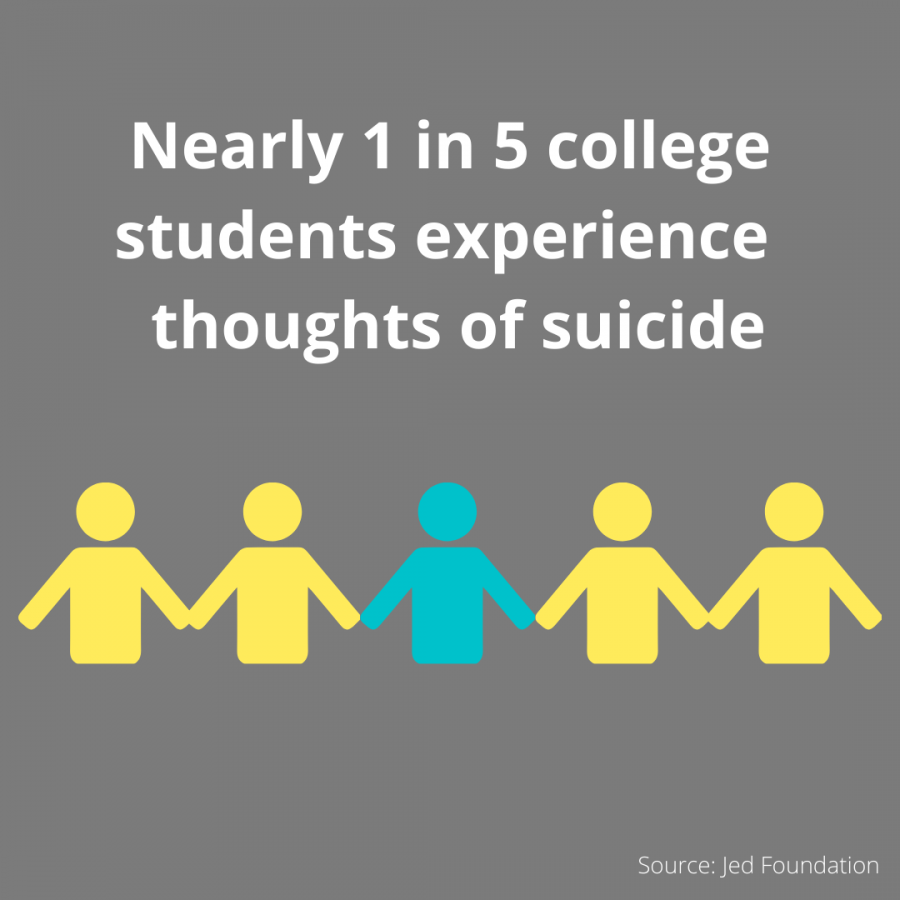

Kubly was not alone. Nationally, suicide claims the lives of 44,193 people every year. About 1,100 of those are college students. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, about 90 percent of people who die by suicide experienced a mental illness — just like Kubly did.

Despite how widespread these mental health disorders are, neurologists have not yet found a foolproof way to treat mental illnesses.

A lack of knowledge is not just a problem for neurological research efforts. It is a trickle-down issue occurring every time a person is diagnosed with a mental illness. When someone is diagnosed with depression, for example, the treatment is usually an antidepressant prescription, psychotherapy or both. But these treatments are not “one size fits all,” which leaves mental health professionals relying on best practices to specifically treat each patient.

Proper treatments are needed when it comes to mental health in general, but in the college-aged population, time is of the essence. College students are profoundly affected by suicide. It is the second leading cause of death in people ages 15-24 and a leading cause of death in college students.

“75 percent of all lifetime mental illness cases start while somebody is college-age,” David Baker, a professor and associate chair in the college’s department of biomedical sciences, said. “So, if you are going to have an anxiety disorder, if you are going to have depression, there is high probability that those diseases will materialize when you are younger than 24.”

Over the past three years at Marquette, 45-50 percent of students who visited the Counseling Center reported concerns with anxiety, and over 60 percent reported depression, according to Counseling Center data. Each year, the university reports an average of 50 Marquette students are hospitalized for suicidal thoughts or other reasons related to suicide.

“After an incident occurs, there is more interest in ‘what are we doing?’ It feels kind of reactionary,” Nick Jenkins, a counselor and the Counseling Center’s mental health advocacy coordinator said. “But it seems like it should be the question, ‘how can we be more proactive?’”

Today, Kubly’s name can be found on a wall in the College of Health Sciences. The “Charles E. Kubly Mental Health Research Center,” gold letters mark a hallway on the third floor of Marquette’s Schroeder Complex. Here, cutting-edge research is trying to uncover underpinnings of mental disorders with the goal to reduce suicides.

For donors Michael and Billie Kubly, their $5 million research endowment, given in 2015, honors their son and calls for an increase in research on depression.

The center consists of research by nine faculty members in the Department of Biomedical Sciences.

“If everyone could see mental illness as a biological disease, there is hope for a biological cure,” William Cullinan, dean of the College of Health Sciences, said.

The Kubly Center’s research projects address depression, a leading cause of suicide, by looking at it as a biological disease that is rooted in the brain’s structure and function. The researchers’ work reflects the theory that better treatment comes with better antidepressants.

“There’s a good percentage of people who never respond to medication, and that’s a little bit disheartening because the main focus of depression (research) is still that main theory,”Analisa Taylor, a senior in the College of Health Sciences who works in a Kubly Center research lab, said. “There’s so much evidence to show that that doesn’t explain everything, so we can’t keep focusing on that.”

David Baker researches how depression is caused by tiny changes in a brain cell’s blueprint, or DNA.

“The biological impairments in mental health are as biologically based as any physical impairments might be,” Baker said. “There are physical limitations to how high you can jump; and, if your knee is injured, there are even greater limitations. The same is true for all the components that make up mental health.”

Baker’s research aims to prove the theory that mental illness and suicide are biologically-based and are best treated by drugs. Since there are not many effective treatments for mental illnesses, they are responsible for the highest level of what scientists call “disease burden,” or the number of years lost in people’s lives because of early death or time spent living with an illness.

Two other research projects, headed by biomedical sciences faculty Paul Gasser, Douglas Lobner and Robert Wheeler, focus specifically on levels of certain chemicals in the brain that affect stress and pleasure. When the chemicals are off-balance, the researchers believe they change the brain’s structure to cause depression.

“There will be much more effective treatments in the coming years than what there are now, and there’s really no way to know which those areas are,” Baker said. “It’s important to have people working on as many different innovative and promising lines of research as possible.”

The Kubly fund supports theories that are not being explored by any other research institution, Baker said, making the departments work all the more appealing and risky.

“Since working in the lab, I have become a little bit more optimistic about mental illness because the biomedical sciences department is working on different aspects of depression that weren’t normally considered in the past,” Taylor said.

For neuroscientists, lowering disease burden through research is a long path. Two years in, most of the Kubly Center’s projects are still in their exploratory stages, and there is still work to be done.

“This type of research does not happen overnight,” Cullinan said.

This story is part of the Marquette Wire’s “Breaking the Silence” series to increase awareness and start dialogue about suicide in college. Read, watch and listen to more coverage here.